Gandhi and the Natal Indian Ambulance Corp |

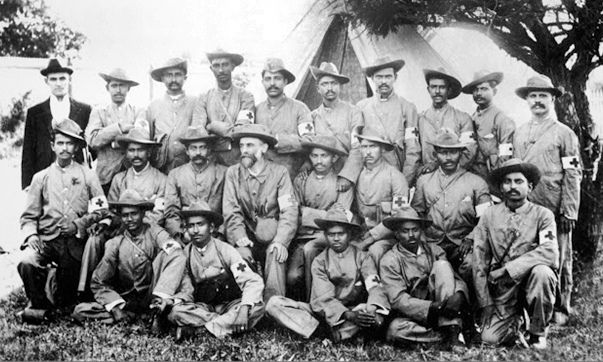

- Heather M. Brown* In the late nineteenth century, the socio-economic status of the indentured Indian population in South Africa changed as the growing ‘Arab’ population challenged white merchants for market dominance. As a result, the white European population retaliated with public prejudice that manifested itself “not only in humiliating, discriminatory social conventions...but also in legislation and municipal ordinances restricting Indian civil rights, franchise and freedom to enter, live and trade at will." It was in South Africa that the once-shy London-educated lawyer from Gujarat, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, spent twenty-one years of his life challenging the “increasingly strident and locally present determination of white settlers to maintain white superiority in matters social, economic and political.”1 The large Indian population of the British colonies in South Africa, led by Gandhi, saw in the Anglo-Boer War an opportunity. Through dedicated military service to the British Raj, Indians could demonstrate to the white colonists their loyalty as British subjects with all the rights, privileges and equal treatment under British law.2 Gandhi encouraged the recruitment of Indian soldiers for service in South Africa with his organization of the Indian Ambulance Corps despite his sympathies for the Boer cause. The objective of Gandhi's service to the British Crown in the Anglo-Boer War was to force the British to recognize Indians as equal citizens of the British Empire. Gandhi's Transformation in the TransvaalGandhi's expedition to South Africa began in 1893 when he was contracted, for one year, by a Porbandar trading-firm to advise their local lawyers in Pretoria. This contract offered Gandhi the opportunity to escape public ridicule after he lost his first case as a barrister in Bombay when his timidity prevented him from cross-examining. Upon returning to his home in Rajkot, he found only “humble legal work of drafting applications and memorials.”3 As Gandhi travelled by train from Durban to Pretoria, he faced racial insults and prejudice that challenged his previous experience with white subjects of the British Empire. Gandhi, possessing a first-class ticket and dressed in English attire, boarded the first-class compartment but was forcibly removed by a police constable at Maritzburg station because a white passenger refused to share the cabin with him. Although there was no single event or occurrence that sparked Gandhi's deep inner transformation, there were a number of worldly experiences, including his physical expulsion from the train, that ultimately shaped his concept of satyagraha, or non-violent resistance.4 In the months following his arrival in South Africa, Gandhi became increasingly aware of the conditions in which indentured Indians, many of whom hailed from South India, found themselves. Upon one occasion, a Tamil laborer, Balasundaram, approached Gandhi seeking legal aid when his master beat him after he revealed that he sought a new employer. According to his autobiography, Gandhi labeled this as the occurrence that marked the beginning of his work among the low caste.5 With Balasundaram, Gandhi's sympathy grew for the indentured laborers, known by the white Europeans as ‘coolies. Gandhi’s determination to better the position of those in the lowest echelons South African society “was an attitude of mind and style of behavior at variance with Hindu perceptions of both a stratified society based on religious merit, and of charity and patronage rather than personal involvement in reform and service as the role befitting the higher caste or more economically privileged.” Gandhi's observations of the hostile Indo-British relations in South Africa led him to write his ʻIndian Home Rule, Hind Swaraj, condemning violent rebellion and encouraging the reversal of Westernization in India.6 As early as 1891, while immersed in his law studies in London, Gandhi's religious, internal and humanitarian enlightenment developed from reading Sir Edwin Arnold's translation of Bhagavad Gita and The Light of Asia, in addition to the Sermon on the Mount. These readings offered “themes of compassion, non-violence and self-renunciation” that, in Gandhi's worldview, formed the highest attributes of religion.7 While in South Africa in 1908-9, Gandhi immersed himself in intellectual and spiritual readings by Lev Tolstoy and John Ruskin in addition to passages from The Bible and an English translation of the Koran. Gandhi worked closely with the Christian evangelists in South Africa who were far more courteous and welcoming than the missionaries he encountered in India. These evangelists welcomed him into their homes, prayer meetings and Christian dialogue in a feeble attempt to secure Gandhi's salvation. However, Gandhi found it difficult to believe that the only way to salvation was through the belief in the son of God, Jesus Christ, suggesting “all men were such and could become God-like.” As he distanced himself from the salvation narrative within the Christian faith, Gandhi gravitated toward Hinduism “with its diverse strands and many paths to salvation, its multitudinous manifestations of the divine in human and natural form, and its understanding of moksha, salvation, in the sense of liberation from a series of lives and their karma.”8 In addition to his readings, Gandhi was greatly influenced by a young Jain jeweler, Rajchandra Ravjibhai Mehta, from whom Gandhi gained reassurance that what he sought after in the spiritual sense “could be found within his own Hindu tradition.” Mehta was also committed to an ethical code of non-violence that complied with the major ideals found in Tolstoy's The Kingdom of God is Within You. As a result, Gandhi began a correspondence with Tolstoy in 1909 in which he described the disparate socio-political conditions attributed to the indentured laborers in South Africa. Tolstoy replied, urging "Indians not to attempt to eject the British by force but to use the weapon of non-participation in the state...for they could only be slaves if they accepted that status and willingly co-operated in the system of enslavement."9 These situations, readings and a continuing dialogue with colleagues shaped Gandhi's concept of satyagraha. His non-violent resistance was first practiced in August 1908 when he led a group of indentured Indians to burn their registration certificates in a great cauldron within the confines of a local mosque in Johannesburg. Those loyal followers of Gandhi's non-violent practices were given the title satyagrahi and their “actions were founded in an implicit trust in human nature, in the conviction that truth would always triumph, and concessions from both parties except on central principles could bring peace.”10 His internal transformation manifested itself externally in the early twentieth century when Gandhi founded two self-sustaining communal settlements in South Africa. Established in 1904, the Phoenix Settlement financed and housed the printing press for Gandhi's newspaper, Indian Opinion. Located near Durban, Phoenix comprised of 100 acres of fruit trees where Gandhi endeavored to retire from life as a barrister and live the rest of his days as a manual laborer. In 1910, Gandhi founded another experimental settlement, Tolstoy Farm, near Johannesburg. Named after the prolific Russian writer, Tolstoy Farm comprised of over 1,000 acres where Gandhi and his followers “built their own houses, and lived on as simple a diet as possible, grinding their own flour, making their own bread, butter and marmalade, and growing their own oranges.” In addition to self-sufficiency, these settlements housed satyagrahi who needed shelter and employment after instances of passive resistance and prolonged imprisonment.11 Gandhi fought for social equality for all, despite the fact that he came from a strict caste social system. His very foundations of social belief shattered with the inculcation of aspects of various religions and molded them in to his concept of satyagraha in order to focus on “the status of Indians as equal citizens of the empire, and their protection against discrimination on overt racial grounds.”12 Domestic Disputes: The Controversy between the Uitlanders and the AfrikanersBy 1898, there was one white population of Afrikaner “farmers descended from the early Dutch settlers” of the South African Cape that challenged the imperialistic power of the British Empire. The Boers suffered defeat in 1881 when they fought against the British in the first war of Boer independence. Their defeat forced the Boers to travel hundreds of miles to the Transvaal and the Orange Free State in order to escape British persecution at Cape Colony.13 British Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain and recently elected High Commissioner for Southern Africa and Governor of Cape Colony, Alfred Milner saw the great exodus of the Boer population to the Transvaal as an impediment in their colonial aspirations.14 These men were self-proclaimed imperialists “because the destiny of the English race, owing to its insular position and its long supremacy at sea, has been to strike fresh roots in distant parts of the world.” Milner went on to claim in his “Credo,” a series of personal notes intended for publication, that his patriotism knew “no geographical but only racial limits.”15 Chamberlain and Milner soon discovered that the Boer population that settled in the Witwatersrand (the Rand), a rocky hillside in the Transvaal, posed the greatest threat to British coffers. It was the discovery of the world's largest gold seam in 1886 that summoned thousands of British migrant fortune seekers to the Transvaal. Chamberlain and Milner believed that the country’s identity would change in Britain's favor. Although these Uitlanders, or ‘outsiders,’ outnumbered the Boers of the Transvaal, British anxieties heightened over the potential unification of the Afrikaner republics of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State. Led by President Paul Kruger, the Boers found no logical reason why they should share regional power with the British Uitlanders nor did they approve of the way the British treated regional black populations. An Afrikaner alliance had the potential to disrupt the British dominance over the social, political, and economic atmosphere of the region.16 By the mid-1890s, the British Colonial Office optimistically assumed that the annexation of the Transvaal would result from the incorporation “of British enterprise, technology, and migration.”17 Lord Selborne, Under Secretary of State at the Colonial Office, believed that a unified Afrikaner Transvaal would maintain dominance over South Africa. In a letter to newly appointed Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain, Lord Selborne recognized that strong British governance “must revolve around the Transvaal, which will be the only possible market for the agricultural produce or the manufacture of Cape Colony and Natal. The commercial attraction of the Transvaal will be so great that a Union of the African states with it will be absolutely necessary for their prosperous existence.”18 In May 1899, the British government, represented by Milner, arranged a conference at Bloemfontein in the Orange Free State in a final attempt to resolve the differences between the Transvaal and Britain. President Kruger was willing to compromise so long as any concessions did not affect the independence of the Republic. Milner, “in favor of executing justice and righteousness” on the Transvaal, found the franchise question “unreasonable.”19 Milner argued for the citizenship of the Uitlander gold miners as this “would enable them gradually to remedy their principal grievances themselves.”20 Kruger believed Uitlander citizenship would undermine Boer aspirations for independence. Within six days, the conference turned confrontational. Negotiations failed to resolve their differences because the concessions offered to Kruger did not include Boer independence.21 The disastrous conference at Bloemfontein only heightened the British determination to plunge the region into war. By October 1899, the Colonial and War Offices garrisoned over 10,000 imperial troops in South Africa with the summoning of an additional 50,000 reinforcements at the outbreak of hostilities. The rapid mobilization of imperial troops forced the Transvaal and the Orange Free State to present the British with “an ultimatum calling for the withdrawal of Imperial forces from the Transvaal's frontiers and for the recall of all reinforcements.” The British government ignored the ultimatum and proceeded with war preparations.22 By this time, the Transvaal government received thousands of offers of assistance from Cape Colony Afrikaners who reminisced of the British humiliation in the Anglo-Transvaal War of 1880. The Transvaal and Orange Free State had nothing to lose by defending their livelihood. With a grand demonstration of camaraderie, the two Afrikaner republics engaged in a war with the largest empire in the world.23 The Battle for Boer Independence and the Natal Indian Ambulance CorpsAt the outbreak of the Anglo-Boer War, Gandhi's approach to the conflict was one of flexible idealism. Although Gandhi did not grow up in a household marked by rigid Hindu orthodoxy, Hinduism certainly influenced his worldview. He “recognized the immorality of war” and that his “participation in war could never be consistent with ahimsa,” or non-violence.24 However, Gandhi recognized that the continuation of humanity's existence often involved violence and with regard to his nationalism, Gandhi interpreted his role as one of service to the British raj.25 Although the British government did not deploy the Indian Army to South Africa during the Boer War, the voluntary participation of a group of Indians was instrumental in supporting the Royal Army. The Boer invasion of Natal in October 1899 gave Gandhi and his like-minded followers the opportunity to garner political benefit by demonstrating their dedication to the Empire even though Gandhi's “personal sympathies were all with the Boers.”26 As soon as news of the hostilities reached Gandhi, he wrote to the Colonial Secretary of Natal enclosing a list of Indians “who have offered their services unconditionally” and “without pay” to Imperial authorities. Gandhi admitted that the volunteers had not received combat training and did not know how to handle weapons. However, Gandhi suggested that there were “other duties no less important to be performed on the battlefield.” Gandhi and the volunteers considered it a “privilege” to be called upon to support the military operations of the British Crown. Initially, the Natal Government ignored their offer of assistance but the Boers demonstrated more “pluck, determination and bravery than had been expected” and the services of the volunteers were needed.27 As a result of Gandhi’s persistence, a volunteer Indian Ambulance Corps formed in late-October 1899. The Natal Indian Ambulance Corps comprised of 300 free Indians, of which “thirty-seven were looked upon as leaders” by the additional 800 indentured laborers from the sugar plantations. The indentured Indians were under the supervision of English overseers hired by their respective owners to prevent desertion. The volunteers of the Ambulance Corps served as dhoolie (stretcher) bearers who received basic medical instruction, including first aid, the dressing of wounds, ambulance training and the administering of medication, from Dr. Lancelot Parker Booth, a Christian clergyman and medical officer.28 According to the Royal Army Medical Corps, a Bearer Company, composed of one stretcher with two bearers which equates to eight stretchers accompanied by sixteen bearers. Collecting and Dressing Stations were created out of the larger Field Hospital that supplied an additional five dhoolies with thirty-two dhoolie bearers.29 The volunteers’ service to the Natal Government was unconditional though the Imperial authorities granted the Indian Ambulance Corps “immunity from service within the firing line.” General Redvers Buller did not force the volunteers to collect the wounded under fire. However, there was a mutual unspoken understanding that if the Corps “undertook it voluntarily, it would be greatly appreciated.” Gandhi claimed the Corps “never liked to remain outside” the danger zone as medical orderlies and “therefore welcomed this opportunity.” Their first task was to tend to the casualties after the British defeat at Colenso.30  Indian Ambulance Corps. Dr. L. P. Booth and M. K. Gandhi, middle row 4th and 5th from left. On 15 December 1899, at Colenso, one of the wounded men whom Gandhi attended to was the only son of Field Marshall Lord Frederick Roberts. The British artillerymen “serving the guns of the 14th and 66th Batteries, Royal Field Artillery, had all been either killed, wounded, or driven from their guns by Infantry fire at close range,” and twelve field guns were deserted and exposed along the Tugela River. Lieutenant Freddy Roberts with Captain Walter Norris Congreve of the Rifle Brigade gathered a small band of cavalry to retrieve the abandoned weaponry. Lieutenant Roberts fell from his horse, badly wounded in three places, as the area fell under heavy shell and rifle fire. The Indian Ambulance Corps “had the honor of carrying the body from the field.” British fatalities at Colenso totaled 143 including Lieutenant Roberts who died from his wounds three days later.31 By early January, a small division of armed Boers defended the summit of Spion Kop, a plateau overlooking the Tugela River approximately 235 miles north of Colenso. Lieutenant General Charles Warren and a mixed force of the Royal Lancaster infantry regiment and Uitlanders, under orders from General Buller, scaled the rocky plateau under the cover of night and fog. The small enemy picket surrendered and fled without a fight. Confident of victory, the British dug a rudimentary trench to defend their position. Unbeknownst to Warren, the British position was completely exposed to a larger Boer artillery force from the surrounding hills because they did not scale the highest point of the Kop. The Boer arsenal included the Maxim gun and Mauser rifles with accuracy up to 2,000 yards. Nicknamed 'the pom-pom' after the sound of its fire, the water-cooled Maxim automatic machine gun was operated by a crew of four artillerymen. The 0.45-inch Maxim fired 500 rounds per minute, which was fifty times faster than the fastest rifle available at the time. As the mist cleared on the morning of January 24, 1900, the battle began.32 Hill warfare, as experienced at the Battle of Spion Kop, posed the greatest difficulty for the Ambulance Corps. In cooperation with a European Ambulance Corps and The Royal Army Medical Corps, access to medical treatment relied upon “the Bearer Company and animal transport for the removal of the wounded from the firing line to the dressing station.” Gandhi recalled that the area of military operations, at the summit of the plateau of Spion Kop, had “no made roads between the battlefield and the base-hospital and it was therefore impossible to carry the wounded by means of ordinary transport.”33 Winston Churchill, who would later despise Gandhi and the India independence movement, joined the volunteer South African Light Horse regiment while performing his duties as war correspondent for the London-based Morning Post. Churchill witnessed “a fierce and furious shelling” that caused many injuries and fatalities. Gandhi and his dhoolie-bearers worked quickly and efficiently to remove the wounded from Spion Kop. Churchill recounted “a village of ambulance waggons [sic] grew up at the foot of the mountain. The dead and injured, smashed and broken by the shells, littered the summit till it was a bloody, reeking shambles.” Churchill, assessing the battle through his spyglass, did not notice that Gandhi was one of the two dhoolie-bearers who carried the mortally wounded General Edward Woodgate down the hillside. As Churchill ascended the Kop to offer reinforcement, thousands of wounded met him as they descended “staggering along alone, or supported by comrades, or crawling on hands and knees, or carried on stretchers.” Gandhi and his volunteers marched twenty-five miles, carrying badly wounded soldiers and officers, from the battlefield to the base-hospital because the ambulances could not traverse the rocky terrain. Their march began at eight o’clock in the morning for prompt arrival at the base-hospital by five o'clock in the afternoon. Along the way, the volunteers tended to open wounds, redressed bandages and administered medicines.34 Not long after the Battle of Spion Kop, the Indian ambulance corps dissolved. Gandhi and thirty-seven volunteered were recipients of the War Medal that “bore the Queen’s portrait on one side and a helmeted Britannia on the other, summoning to her aid the men of South Africa.” Gandhi later received the Kaisar-i-Hind gold medal for his humanitarian work in South Africa and the Zulu War medal for his renewed ambulatory services in 1906. He would later return these medals as a demonstration that he could “retain neither respect nor affection for such a government” that continued to act “in an unscrupulous, immoral and unjust manner” towards their Indian subjects.35 Gandhi used his involvement in the Anglo-Boer War as the means to force the British Raj to recognize Indians as equal citizens of the empire. As army medics, the Natal Indian Ambulance Corps had the potential to impress the Imperial government with their unwavering courage and dedication.36 Additionally, Gandhi's participation fostered in him a religious awakening and spiritual preparedness for his future ascetic Hindu lifestyle of a brachmachari. Although the Natal Indian Ambulance Corps did not immediately bring about an era of equality for all British citizens of the empire in South Africa, their participation in the war proved their resilience to transcend the boundaries of country and ethnicity to create unity in the region. References:

Bibliography:

* Heather M. Brown, Instructional Assistant to Dr. Tillman, Department of History, Texas State University. Email: hb1125@txstate.edu |