Some men changed their times...

One man changed the World for all times!

Comprehensive Website on the life and works of

Mahatma Gandhi

+91-23872061

+91-9022483828

info@mkgandhi.org

+91-23872061

+91-9022483828

info@mkgandhi.org

Inspiring Stories from Gandhi's Life(For all ages) |

- Uma Shankar Joshi I

The night was very dark and Mohan was frightened. He had always been afraid of ghosts. Whenever he was alone in the dark, he was afraid that a ghost lurking in some dark corner would suddenly spring on him. And tonight it was so dark that one could barely see one's own hand. Mohan had to go from one room to another. As he stepped out of the room, his feet seemed to turn to lead and his heart began to beat like a drum. Rambha, their old maidservant was standing by the door. "What's the matter, son?" she asked with a laugh. "I am frightened, Dai," Mohan answered. " Frightened, child! Frightened of what?" "See how dark it is! I'm afraid of ghosts!" Mohan whispered in a terrified voice. Rambha patted his head affectionately and said, "Whoever heard of anyone being afraid of dark! Listen to me: Think of Rama and no ghost will dare come near you. No one will touch a hair of your head. Rama will protect you." Rambha's words gave Mohan courage. Repeating the name of Rama, he left the room. And from that day, Mohan was never lonely or afraid. He believed that as long as Rama was with him, he was safe from the danger. This faith gave Gandhiji strength throughout his life, and even when he died the name of Rama was on his lips. II

Mohan was very shy. As soon as the school bell rang, he collected his books and hurried home. Other boys chatted and stopped on the way; some to play, others to eat, but Mohan always went straight home. He was afraid that the boys might stop him and make fun of him. One day, the Inspector of Schools, Mr. Giles, came to Mohan's school. He read out five English words to the class and asked the boys to write them down. Mohan wrote four words correctly, but he could not spell the fifth word 'Kettle'. Seeing Mohan's hesitation, the teacher made a sign behind the Inspector's back that he should copy the word from his neighbour's slate. But Mohan ignored his signs. The other boys wrote all the five words correctly; Mohan wrote only four. After the Inspector left, the teacher scolded him. "I told you to copy from your neighbour," he said angrily. "Couldn't you even do that correctly?"Every one laughed. As he went home that evening, Mohan was not unhappy. He knew he had done the right thing. What made him sad was that his teacher should have asked him to cheat. IIIIn South Africa Gandhiji set up an ashram at Phoenix, where he started a school for children. Gandhiji had his own ideas about how children should be taught. He disliked the examination system. In his school he wanted to teach the boys true knowledge—knowledge that would improve both their minds and their hearts. Gandhiji had his own way of judging students. All the students in the class were asked the same question. But often Gandhiji praised the boy with low marks and scolded the one who had high marks. This puzzled the children. When questioned on this unusual practice, Gandhiji one day explained, "I am not trying to show that Shyam is cleverer than Ram. So I don't give marks on that basis. I want to see how far each boy has progressed, how much he has learnt. If a clever student competes with a stupid one and begins to think no end of himself, he is likely to grow dull. Sure of his own cleverness, he'll stop working. The boy who does his best and works hard will always do well and so I praise him." Gandhiji kept a close watch on the boys who did well. Were they still working hard? What would they learn if their high marks filled them with conceit? Gandhiji continually stressed this to his students. If a boy who was not very clever worked hard and did well, Gandhiji was full of praise for him. IV

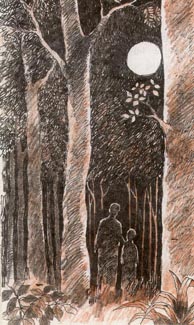

This incident occurred when Gandhiji was practising law in the city of Johannesburg in South Africa. His office was three miles from his house. One day a colleague of his, Mr. Polak, asked Gandhi's thirteen-year old son, Manilal to fetch a book from the office. But Manilal completely forgot till Mr. Polak reminded him that evening. Gandhiji heard about it and sent for Manilal. He said, "Son, I know the night is dark and the way is long and lonely. You will have to walk nearly six miles but you gave your word to Mr. Polak. You promised to fetch his book. Go and fetch it now." Ba and the family were upset when they heard of Gandhi's decision. The punishment seemed far too severe. Manilal was only a child, the night was dark and the way lonely. He had only forgotten a book after all. It could be brought the next day. This was what they all felt, but no one had the courage to say anything. They knew that once Gandhiji's mind was made up, nobody could change it. At last Kalyan Bhai plucked up courage. "I'll fetch the book," he offered. Gandhiji was gentle but firm, "But the promise was made by Manilal.""Very well, Manilal will go but let me go with him," Kalyan Bhai pleaded. Gandhiji agreed to this and Manilal set off with Kalyan Bhai to fetch the book. The kind and gentle Gandhiji could be firm as a rock at times. He saw that Manilal kept his word and did as he had promised. VSoon after Gandhi's return from South Africa, a meeting of the Congress was held in Bombay. Kaka Saheb Kalelkar went there to help. One day Kaka Saheb found Gandhiji anxiously searching around his desk. "What's the matter? What are you looking for?" Kaka Saheb asked. "I've lost my pencil," Gandhiji answered. "It was only so big." Kaka Saheb was upset to see Gandhiji wasting time and worrying about a little pencil. He took out his pencil and offered it to him. "No, no, I want my own little pencil," Gandhiji insisted like a stubborn child. "Well, use it for the time being," said Kaka Saheb. "I'll find your pencil later. Don't waste time looking for it now." "You don't understand. That little pencil is very precious to me," Gandhiji insisted. "Natesan's little son gave it to me in Madras. He gave it with so much love and affection. I cannot bear to lose it." Kaka Saheb didn't argue any more. He joined Gandhiji in the search. At last they found it - a tiny piece, barely two inches long. But Gandhiji was delighted to get it back. To him it was no ordinary pencil. It was the token of a child's love and to Gandhiji a child's love was very precious. VIChildren loved visiting Gandhi. A little boy who was there one day, was greatly distressed to see the way Gandhiji was dressed. Such a great man yet he doesn't even wear a shirt, he wondered. "Why don't you wear a kurta, Gandhi?" the little boy couldn't help asking finally. "Where's the money, son?" Gandhi asked gently. "I am very poor. I can't afford a kurta." The boy's heart was filled with pity. "My mother sews well", he said. "She makes all my clothes. I'll ask her to sew a Kurta for you." "How many Kurtas can your mother make?" Gandhiji asked. "How many do you need?" asked the boy. "One, two, three.... she'll make as many as you want." Gandhi thought for a moment. Then he said, "But I am not alone, son. It wouldn't be right for me to be the only one to wear a kurta." "How many Kurtas do you need?" the boy persisted. "I'll ask my mother to make as many as you want. Just tell me how many you need." "I have a very large family, son. I have forty crore brothers and sisters," Gandhiji explained. "Till every one of them has a kurta, how can I wear one? Tell me, can your mother make kurtas for all of them? At this question the boy became very thoughtful. Forty crore brothers and sisters! Gandhiji was right. Till every one of them had a kurta to wear how could he wear one himself? After all the whole nation was Gandhi's family, and he was the head of that family. He was their friend, their companion. What use would one kurta be to him? VII

One day Gandhi and Vallabhbhai Patel were talking in the Yeravda jail when Gandhi remarked, "At times even a dead snake can be of use." And he related the following story to illustrate his point: Once a snake entered the house of an old woman. The old woman was frightened and cried out for help. Hearing her, the neighbours rushed up and killed the snake. Then they returned to their homes. Instead of throwing the dead snake far away, the old woman flung it onto her roof. Sometime later a kite flying overhead spotted the dead snake. In its beak the kite had a pearl necklace which it had picked up from somewhere. It dropped the necklace and flew away with the dead snake. When the old woman saw a bright, shining object on her roof she pulled it down with a pole. Finding that it was a pearl necklace she danced with joy! When Gandhi finished his story, Vallabhbhai Patel said he too had a story to tell: One day a bania found a snake in his house. He couldn't find anyone to kill it for him and hadn't the courage to kill it himself. Besides, he hated killing any living creature. So he covered the snake with a pot and left it there. As luck would have it, that night some thieves broke into the bania's house. They entered the kitchen and saw the overturned pot. "Ah," they thought, "the bania has hidden something valuable here." As they lifted the pot, the snake struck. Having come with the object of stealing, they barely left with their lives. VIIIGandhi went from city to city, village to village collecting funds for the Charkha Sangh. During one of his tours he addressed a meeting in Orissa. After his speech a poor old woman got up. She was bent with age, her hair was grey and her clothes were in tatters. The volunteers tried to stop her, but she fought her way to the place where Gandhi was sitting. "I must see him," she insisted and going up to Gandhi touched his feet. Then from the folds of her sari she brought out a copper coin and placed it at his feet. Gandhi picked up the copper coin and put it away carefully. The Charkha Sangh funds were under the charge of Jamnalal Bajaj. He asked Gandhi for the coin but Gandhi refused. "I keep cheque worth thousands of rupees for the Charkha Sangh," Jamnalal Bajaj said laughingly "yet you won't trust me with a copper coin." "This copper coin is worth much more than those thousands," Gandhi said. "If a man has several lakhs and he gives away a thousand or two, it doesn't mean much. But this coin was perhaps all that the poor woman possessed. She gave me all she had. That was very generous of her. What a great sacrifice she made. That is why I value this copper coin more than a crore of rupees." IXThis incident occurred in Noakhali. After the Hindu-Muslim riots Gandhi toured the area on foot to reassure and comfort the people. He would set off from a village soon after dawn and arrive at the next village after sunset. On arrival he would first attend to his work then he would take a bath. Gandhi used a rough stone to clean his feet. Miraben had given this stone to him many years ago and Gandhi had kept it carefully ever since. He took it with him everywhere. One evening after they had arrived at a village and Manu was getting Gandhi's bath ready, she noticed that the stone was missing. She looked everywhere but could not find it. She told Gandhi that the stone was lost and added, "It must have been left behind at the weaver's where we stayed yesterday. What should I do now?" Gandhi thought for a moment. Then he said, "Go and fetch the stone. If you suffer once, you'll not forget another time." "Can I take someone with me?" Manu asked. "Why?" questioned Gandhi. Manu was silent. She did not want to admit that she was frightened to go alone. The road to the village lay through forests of betel nut and coconut and it was easy to lose one's way. Besides, Manu was barely sixteen years old and she had never gone anywhere alone. But she could not think of an answer. So Manu took the path they had taken earlier in the day. Carefully following the old footprints she managed to reach the village and find the weaver's house. The old woman who lived there recognised her and welcomed her warmly. Tired and rather irritated Manu told her why she had come. But how was the old woman to have known that that bit of stone was so valuable? She had thrown it away with the rubbish. They both began to search for it. At last much to Manu's joy they found it. Manu had left the house at 7.30 in the morning. By the time she returned it was past one in the afternoon. She had walked nearly fifteen miles. Worn out, hungry and irritated she went straight to Gandhi and put the stone in the lap. Then she burst into tears. "This stone was a real test for you," Gandhi told her gently. "Do you know that this stone has been with me for the last twenty-five years. It has gone with me everywhere, from jails to mansions. I can easily get another stone like it, but I wanted you to learn that it is bad to be careless." "I've never prayed as hard as I did today," said Manu. "I want to make women brave and fearless", Gandhi said. "Today not only you but I too learnt a lesson." Manu did not say anything but she must have thought Gandhi's methods were very unusual. |