Gandhi and Swaraj in Ideas: Some Reflections |

|

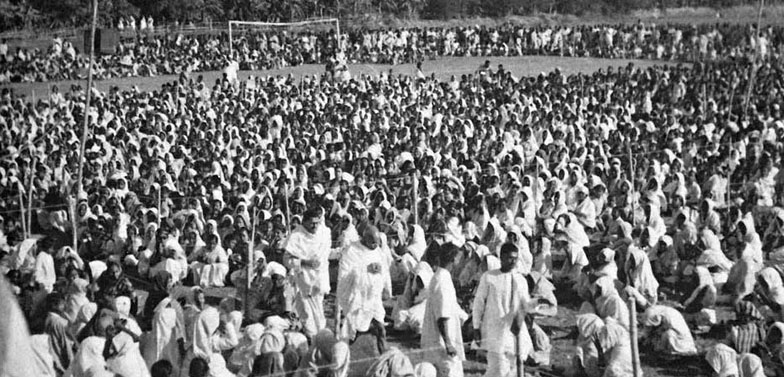

Prof. Gita Dharampal, Dean, Research, Gandhi Research Foundation [This is a shortened and slightly edited version of Prof. Gita Dharampal’s introductory remarks at the Webinar on 15th January 2021, with Keynote speaker, Lord Bhikhu Parekh, in the Distinguished Lecture Online Series organised jointly by the Gandhi Study Circle/Zakir Husain Delhi College, Delhi University and the Gandhi Research Foundation.] Firstly, I’ll say a few words about the definition and centrality of the term Swaraj in Indian public discourse. Secondly, it is, of course, necessary to highlight the revolutionary conception and application of Swaraj (first and foremost of ‘Swaraj in Ideas’) as articulated so forcefully in Gandhi’s political manifesto Hind Swaraj. And thirdly, I’ll briefly indicate, what’s the take-away for us, today, with a promise for the future. So, firstly, what is our understanding of Swaraj? In a nutshell, Swaraj, a hallowed multivalent concept – with moral and spiritual connotations – signifies (in particular, from the political science perspective) ‘self-governing’ or ‘people’s democracy’ in the truest sense of the term, and, as a ‘signifier’, Swaraj is integral to the foundation of Indian polity, her praxis and ethos. As such, the concept can be traced back genealogically to Vedic antiquity. Swaraj, as an idea, has been imagined and reimagined, and constituted a political goal to be realised even before our historic freedom struggle against the British Raj. To cite one concrete instance: the rousing call Hindavi Swaraj was employed as a cardinal emblem of political resurgence under Chhatrapati Shivaji in the 17th century, to be precise as early as 1645. Two and a half centuries later, notably an Anglo-Gujarati Journal called Hind Svarajya was published in the 1st decade of 20th century. But this pedigree does not diminish the unique importance of Gandhi’s political manifesto Hind Swaraj (1909) that constitutes the focal point of our attention today. Yet, whilst acknowledging Gandhi’s preeminence, we should, however, not forget that it was Lokmanya Tilak who popularized the concept of Swaraj about half a decade before Gandhi, during the Swadeshi Movement of 1905, by proclaiming “Swaraj is my birth-right and I will have it”. For Tilak, Swaraj meant the establishment of a democratic state in which the rights and liberties of the people were held to be sacrosanct. But for us today, whilst we are rethinking the concept of Swaraj – in postcolonial India, on the eve of our celebrations for the 75th anniversary of our political Independence (however deficient it may be for the majority of our population), it is, nonetheless, the enhanced concept of “Swaraj in Ideas”, signalling a ‘decolonisation of the mind’ that has come to have an even more crucial importance than the normative political understanding of Swaraj. And now I turn to the second point: Amazingly, more than a century ago, it was Gandhi who realised the urgent need for initiating a crucial cognitive ‘liberation’ or intellectual transformative emancipation – in particular among the Westernized elite of India who were in fact the addressees of his dialogic treatise Hind Swaraj. This view is confirmed by others; yet it is T.K. Mahadevan, the well-known critic, who proclaimed that, thanks to this intellectual emancipatory quality, Hind Swaraj, with its aim to bring about a “Swaraj in Ideas”, represents a work of greater significance than Rousseau's Social Contract and Karl Marx's Das Kapital. For, unlike these two books, Hind Swaraj did not mark the end of an age, but instead "the beginning of a new order". As such, Gandhi’s political manifesto constitutes a compelling and unsettling treatise, first and foremost, because it incisively rejects the “trappings of modernity” – and this at the beginning of the 20th century –at the zenith of modern civilisation’s accomplishments – which indeed testifies not only to Gandhi’s original thinking, but also to his incredible audacity! Yet, with discerning logic, Gandhi’s objective, as is well-known, is to intellectually counteract British colonialism’s hegemonic influence over the colonised Indian elite by astutely subverting the legitimacy of the colonial enterprise at its core, namely, by deconstructing its professed ‘civilising mission’ (epitomized by the Indian railways, law courts, modern medicine and English education). This indeed constitutes a first ground-breaking cognitive step on the road towards ideological liberation. Further, calling modern civilisation a ‘disease’ to which, according to him, the English had fallen ‘victim’, Gandhi rhetorically turns the tables on colonial discourse which branded Indian society and environment as being ‘diseased’. It would seem that Gandhi’s dexterous exercise in intellectual acrobatics aims to shake the very foundations of the economic and political structures which were held sacrosanct at the time. With the intention of extricating the Indian Westernized elite from the lure of modernity, Gandhi endeavours to remove its mental mesmerisation vis-à-vis this “nine days’ wonder”, namely, flimsy modernity which, according to Gandhi, had no deeprooted foundations. So, thirdly, what is the takeaway for us today? It is meant as a wake-up call: for with his ‘Swaraj in Ideas’, Gandhi was above all intent on foregrounding independence of thought and action among the Indian political strata, reinforced by integrity and commitment, qualities that are certainly in short supply in the present, and need urgently to be practised. Gandhi’s exhortation for a ‘Swaraj in Ideas’ was meant to bring about an ethically grounded cognitive transformation in the Indian status quo. Significantly, for him, embracing whole-heartedly one’s own civilization was the first step towards attaining Swaraj (‘the rule of the self by the self’). Yet this affirmation of one’s own culture, which for him constituted part and parcel of the process of self-realization, had per force to be accompanied by societal reform, and correspondingly self-purification, before real Swaraj, or self-transformation could be achieved: “It is Swaraj when we learn to rule ourselves”, he proclaimed. For us today, this ‘will-to-selfhood’ involves a renovation and intellectual re-equipment of the self, whereby, in Gandhi’s mental landscape, intellectual and spiritual mastery and freedom of the self are one and the same, namely Swaraj. But physical and intellectual empowerment and liberation – be they collective or pertaining to the self – to Gandhi’s defiant spirit, also necessitated, and still necessitates, a contestatory exercise, comprising a radical deconstruction of stereotypical believes, colonial indoctrination and myth-making, in order to initiate a much needed ‘Swaraj in ideas’. Unfortunately, though initiated by him, only faltering attempts in this direction have been made in the past 7 ½ decades. So, today, at the beginning of the 2nd decade of 21st century, inspired by Gandhi’s example, we are called upon to engage not only in revoking the so-called ‘imperialism of western categories’, but also in establishing a framework of indigenous conceptual categories that would reinvigorate Indian public discourse, thereby strengthening our intellectual independence and national well-being.  Mahatma Gandhi addressing a public meeting, Mahishadal, West Bengal, December 1946 Courtesy: 'Khoj Gandhiji Ki', January-February 2021, Published by Gandhi Research Foundation |