Some men changed their times...

One man changed the World for all times!

Comprehensive Website on the life and works of

Mahatma Gandhi

+91-23872061

+91-9022483828

info@mkgandhi.org

+91-23872061

+91-9022483828

info@mkgandhi.org

What Tolstoy wrote in his letters to Gandhi, influencing his path toward AhimsaIn the last year of his life, Leo Tolstoy, the Russian literary giant, exchanged letters with a young MK Gandhi. This correspondence would not only strengthen Gandhi’s conviction in the practice of Ahimsa but also influence his ideas of Satyagraha and Swadeshi. |

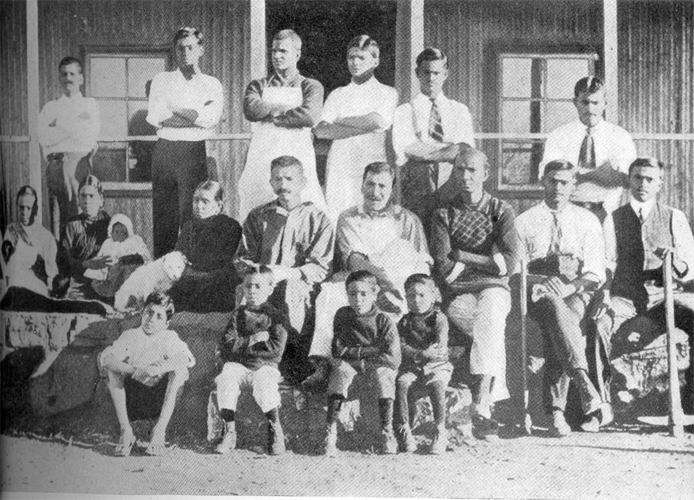

- Edited by Yoshita RaoBefore Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (1869-1948) became a central player in the freedom struggle, he read a lot of Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy, also known as Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910). The Russian is one of the greatest literary figures of all time. Calling him the “greatest apostle of non-violence that the present age had produced” and “a great teacher whom I have long looked upon as one of my guides”, Gandhi’s conviction of taking the path of Ahimsa (non-violence) was inspired by the Russian author. He once said, “Tolstoy’s The Kingdom of God is Within You overwhelmed me. It left an abiding impression on me.” He went on to articulate how the book embodied independent thinking, truthfulness and made him a firm believer in Ahimsa. Gandhi also shared a profound correspondence with Tolstoy as the latter was nearing the end of his life. And it all began in 1908, when an Indian revolutionary, Taraknath Das, asked for the prodigious author’s support for India’s fight against British colonialism. On 14 December, Tolstoy replied in a long and profound letter which he reproduced in the ‘Free Hindustan’ newspaper. His letter to Das eventually found its way to a young Gandhi who was making his mark in South Africa back in 1909. Gandhi sought Tolstoy’s permission to republish this letter in his South African publication called the Indian Opinion. His letter, which was written in Russian, was later published in English under the title ‘A Letter to a Hindu’. This exchange evolved into a year-long correspondence that lasted until a few weeks before Tolstoy’s death on 7 November 1910. Law of LoveAccording to Tolstoy, human civilization for centuries has lived and abided by the path of violence as a means to ensure survival. But he believes this way of life is contrary to what he calls the natural “law of love”. Opening each chapter of ‘A Letter to a Hindu’ with a passage from Lord Krishna (Mahabharata) as a backdrop to his arguments, he challenged false religious and pseudo-scientific ideologies that promote violence. “Tolstoy’s letters issue a clarion call for nonviolent resistance. He admonishes against false ideologies—both religious and pseudo-scientific—that promote violence, an act he sees as unnatural for the human spirit, and advocates for a return to our most natural, basic state, which is the law of love. Evil, Tolstoy argues with passionate conviction, is restrained not with violence but with love — something Maya Angelou would come to echo beautifully decades later,” writes Maria Popova, a Bulgarian-born writer of literary and art commentary and cultural criticism. According to Tolstoy, there is one “old and simple truth”, which is, “It is natural for men to help and to love one another, but not to torture and to kill one another.” Strengthening Gandhi’s convictions of advocating nonviolent resistance, Tolstoy said, “Love is the only way to rescue humanity from all ills, and in it, you too have the only method of saving your people from enslavement… Love, and forcible resistance to evil-doers, involve such a mutual contradiction as to utterly destroy the whole sense and meaning of the conception of love.” He even brings up the notion of love to argue how “a commercial company [East India Company] enslaved a nation comprising two hundred millions”: What does it mean that thirty thousand men, not athletes but rather weak and ordinary people, have subdued two hundred million vigorous, clever, capable, and freedom-loving people?… If the people of India are enslaved by violence it is only because they themselves live and have lived by violence, and do not recognize the eternal law of love inherent in humanity…As soon as men live entirely in accord with the law of love natural to their hearts and now revealed to them, which excludes all resistance by violence, and therefore hold aloof from all participation in violence—as soon as this happens, not only will hundreds be unable to enslave millions, but not even millions will be able to enslave a single individual. In another letter to Gandhi on 7 September 1910, which was about 8 weeks before he passed away, Tolstoy returned to the subject with greater conviction: The longer I live — especially now when I clearly feel the approach of death — the more I feel moved to express what I feel more strongly than anything else, and what in my opinion is of immense importance, namely, what we call the renunciation of all opposition by force, which really simply means the doctrine of the law of love unperverted by sophistries. Love, or in other words the striving of men’s souls towards unity and the submissive behaviour to one another that results therefrom, represents the highest and indeed the only law of life, as every man knows and feels in the depths of his heart (and as we see most clearly in children), and knows until he becomes involved in the lying net of worldly thoughts… Any employment of force is incompatible with love. This is something Gandhi recognised quite acutely. In his introduction to Tolstoy’s ‘A Letter to a Hindu’, he notes how the Russian author’s experience as a soldier in the Crimean War (1853-56) gave him a unique insight into what violence can do. Gandhi goes on to ask whether the idea of replacing the English using violence will end up resulting in something worse. “India, which is the nursery of the great faiths of the world, will cease to be nationalist India, whatever else she may become, when she goes through the process of civilization in the shape of reproduction on that sacred soil of gun factories and the hateful industrialism which has reduced the people of Europe to a state of slavery, and all but stifled among them the best instincts which are the heritage of the human family,” he writes. Gandhi goes on to add, “If we do not want the English in India we must pay the price. Tolstoy indicates it: Do not resist evil [with violence], but also do not yourselves participate in evil—in the violent deeds of the administration of the law courts, the collection of taxes and, what is more important, of the soldiers, and no one in the world will enslave you.” Real Influence Down the LineAs Gandhi notes, there is “nothing new” in what Tolstoy preaches, but that his “presentation of the old truth is refreshingly forceful” and that “he endeavours to practice what he preaches”.  Residents at Gandhi’s Tolstoy Farm Such was the influence Tolstoy had that Gandhi and his friend Hermann Kallenbach called their farm in South Africa ‘Tolstoy Farm’. Established in 1910, the farm served as a headquarters for his Satyagraha campaign against the discrimination Indians faced in the South African province of Transvaal. In this Ashram, residents practised notions of self-sufficiency through hard manual labour with an emphasis on values such as truth, non-violence and chastity, among others. It was his experiences here that would, later on, influence his Swadeshi Movement based on the principle of manufacturing and buying goods that are made in one’s own country. The principles of Ahimsa, Satyagraha and Swadeshi would define a lot of what Gandhi would do later in his life, and there is no doubt about Tolstoy’s influence in shaping them. The principles of Ahimsa, Satyagraha and Swadeshi would define a lot of what Gandhi would do later in his life, and there is no doubt about Tolstoy’s influence in shaping them. “Undoubtedly Count Tolstoy has profoundly influenced him (Gandhi),” wrote Reverend Joseph Doke, Gandhi’s first biographer. “The old Russian reformer, in the simplicity of his life, the fearlessness of his utterances, and the nature of his teaching on war and work, have found a warmhearted disciple in Mr Gandhi.” Sources:

Courtesy: The Better India, January 31, 2022. |