A Fistful of Salt: How Women Took Charge of the Dandi March |

- By Malavika Karlekar*

Women’s participation in the salt satyagraha continued well into the 1930s. Women’s involvement in political protest is not new. In the past too, under the mandate of an entrenched patriarchy, women were quick to challenge a worldview that denied them a salience. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was jailed in his struggle against punitive salt laws, and women took on leadership roles. It would perhaps not be too far-fetched to suggest that the country-wide resistance by women to the prohibitive cost of salt – a basic ingredient of daily diet. Gandhi was the catalyst – but the movement was taken forward by scores of women. When Gandhi lifted a fistful of clayey mud embedded with salt crystals from the sea at Dandi on the Gujarat coast on April 6, 1930, the accompanying crowd of mostly men cheered vociferously. Following the Indian National Congress’s call at its 1929 Lahore session for purna swaraj or complete self-rule, Gandhi had carefully planned this dramatic phase of his movement by violating the salt tax. Women had been excluded from the three-week-long march from Ahmedabad’s Sabarmati Ashram – but a few were not to be deterred and made their way to Dandi. Sarojini Naidu had come by car, and along with Mithuben, was there when the first fistful was gathered.

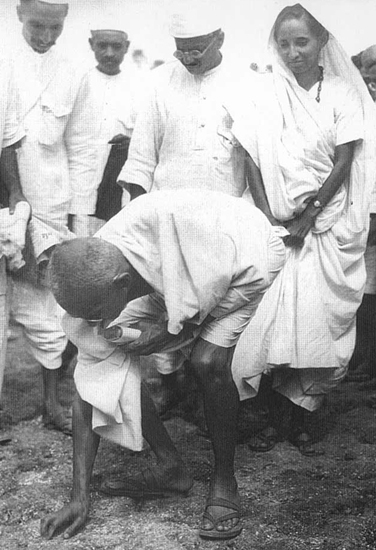

April 6, 1930: Gandhi being greeted by Sarojini Naidu at Dandi. A couple of days later, this popular, much-viewed photograph of the Mahatma, carefully composed from a front angle, with Mithuben Petit behind, was taken at Bhimrad, some 30 miles away from Dandi.

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi collecting salt granules at Bhimrad on the Gujarat coast on April 9, 1930. He is watched by Mithuben Petit and his son, Manilal. The moment for women’s more active and independent participation was around the corner: after the arrest of Gandhi and Abbas Tyabji on May 5, Sarojini Naidu took over and led the march and raid on the salt works at Dharsana. Many satyagrahis were brutally beaten to death by the police, and the incident received worldwide publicity through the report of the American journalist, Webb Miller. Earlier, perhaps fearing such an outcome, the Mahatma had been ambivalent about women’s participation in what could become a difficult protest, saying that just as it would be “cowardice for Hindus to keep cows in front of them while going to war, similarly it would be considered cowardly to keep women with them on the march”. He felt that though women satyagrahis were very keen on joining the growing civil disobedience movement, they were best suited to picket liquor shops and spin khadi. On April 10, 1930, in a piece titled ‘To the Women of India’ published in Young India, he wrote: “I feel that I have now found that work. …Let the women of India take up these two activities, specialise in them; they would contribute more than man to national freedom. They would have an access of power and self-confidence to which they have hitherto been strangers.” Accordingly, a women’s conference was held at Dandi on April 13, which passed a resolution on prohibition.

Ameena Tyabji, Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay and Kasturba Gandhi, perhaps at Sabarmati Ashram, March 1930. That the access to salt resonated with women is evocatively described by Kamaladevi Chattopadhayay in Indian Women’s Battle for Freedom: “The salt satyagraha must stand out as not only unique but as an incredible form of revolution in human history. The very simplicity of this weapon was as appealing as intriguing. So far as women were concerned it was ideally tailor-made for them. As women naturally preside over culinary operations, salt is for them the most intimate and indispensable ingredient’ (p. 106). Clearly, women were not to be daunted nor afraid of police batons; consequently, Kamaladevi wasted little time in organising volunteers for a variety of programmes, including prabhat pheris (early morning processions) and gathering salt and brine at Chowpatty and Juhu beaches. In Bombay, the air was soon full of cries of 'namak kaida toda hai (we have broken the salt law), 'Inquilab Zindabad' and 'Mahatma Gandhi ki jai'.”

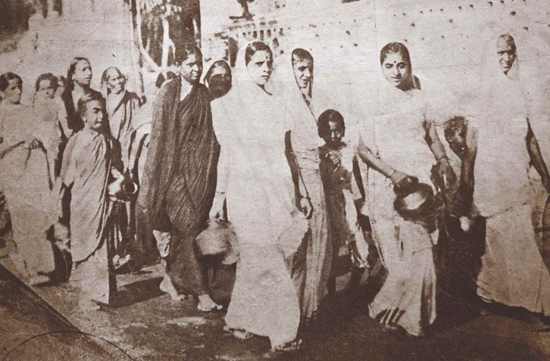

A prabhat pheri in Bombay. As Chattopadhayay and other women marched to Chowpatty to collect sea water to be evaporated on makeshift stoves or chulhas, the police arrived. Hit by a lathi (baton), Kamaladevi wrote, “a rough boot pushed me aside and I came down with my arm on the burning pole”. She refused to call off the protest or take medical aid. Soon, despite police attempts, the crowds grew and several women leaders and housewives carrying pots and pans joined the movement. On April 16, 1930, over 500 people led by Chattopadhayay marched to the Wadala salt depot near Bombay. An eyewitness reported that a woman “climbed through the barbed wire and approached the salt mound as though it was an altar, and filled her sari with salt as part of some unknown ritual”.

Avantikabai Gokhale (a close friend of Kamaladevi Chattopadhayay’s) organised salt making at multiple locations. Here she leads a group of women in Dadar who are returning with pots of sea water. In the months to follow, as the movement spread, women in all three presidencies in – if not organised – marches to the nearest sea coast to collect salty clay and brine. As a part of the activities following the Dandi salt march, on October 26, Avantikabai Gokhale organised a hoisting of the Congress flag at Azad Maidan in Bombay. As this was in violation of the Police Commissioner’s ban on such activities, she was arrested and imprisoned for six months. Dandi and the events surrounding it provided ‘photo ops’ to the vernacular press and nationalistic newspapers such as Mumbai Samachar, The Free Press Journal and The Bombay Chronicle, where cameos of prominent participants and on-site ‘action’ photographs were prominently displayed over several months. As with the protests against salt laws, those against the CAA have not lacked media attention. The scale and variety of recordings today are of course very different: mobile grabs, videos as well as well-composed professional photographs provide a continuum, a visual history that records for generations to come the ability of Indian women to be politically active in nonviolent but invincible protests. Courtesy: This article has been adapted from The Wire, dt. 30.1.2020 * Malavika Karlekar is co-editor, Indian Journal of Gender Studies and curator, Re-presenting Indian Women: A Visual Documentary 1875-1947, both at the Centre for Women's Development Studies, New Delhi. All photographs are from the National Gandhi Museum newspaper archives, New Delhi. |