Ambidextrous Gandhi |

- By Hari Nair1 and Swaha Das2If there is one piece of writing that reflects Gandhian Thoughts - from the 98 volumes of the Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi (CWMG) - it is the Hind Swaraj. The original manuscript had 275 pages. Of these 40 were written by Gandhi with his left hand while returning from England to South Africa on board a ship. Why did he write with his left hand? Was he in a rush? There might be a story to tell.

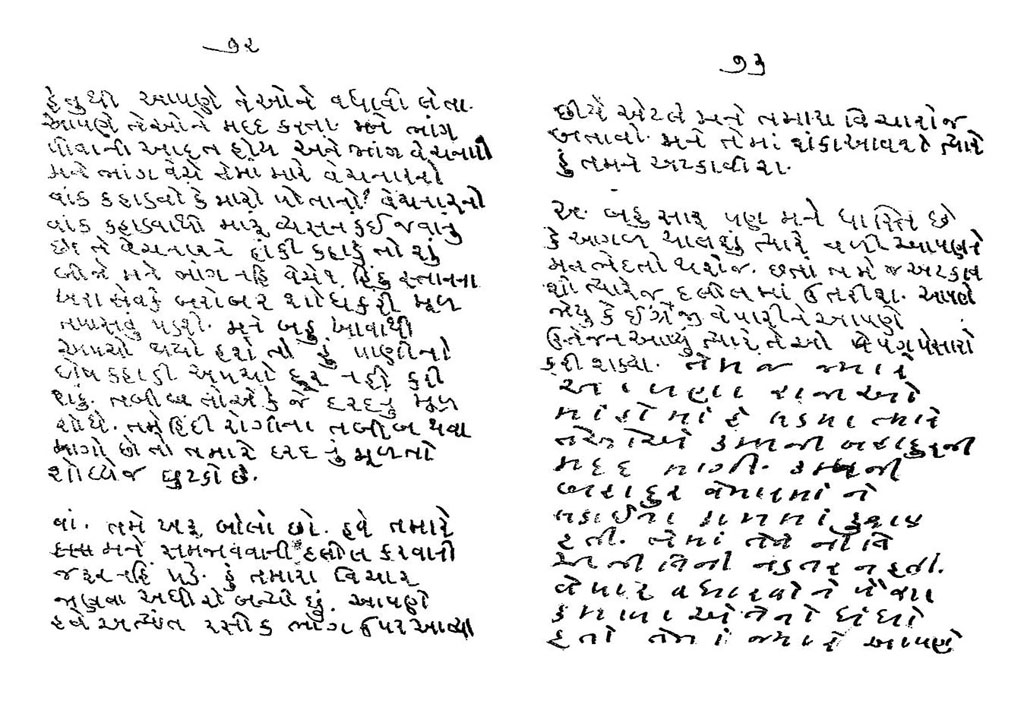

This is a digital facsimile of pages 62 and 63 of the Hind Swaraj manuscript (Navjivan 1923 edition). Gandhi visited London five times: first, as a student between 1888 and 1891; his second visit was in 1906; third, in 1909; fourth, in 1914; and the last one in 1931. During the second and third visits, he engaged with a number of individuals, who belonged to the Indian School of Anarchists. Many of those anarchists rationalized and justified violence against British imperialists – including Shyamji Krishna Varma and Vinayak Damodar Savarkar. Varma, who was trained in Sanskrit and Law, founded the India House in London as a residence for young Indian students. Those students received fellowships from him for studying in England under the condition that they would never accept an office under the British government. But India House was also a hostel, where young Indians were radicalized towards the path of terror. Gandhi feared the outcome of such mentoring of young adults by these Indian anarchists. That fear was realized during Gandhi’s third visit to London in July, 1909. Ten days prior to Gandhi’s arrival, a young Punjabi student named Madan Lal Dhingra with connections to the India House assassinated Sir William Curzon-Wylie – an aide to the Secretary of State for India. Dr Cowasji Lalcaca, who tried to save Sir William, was caught in the line of fire and succumbed to his injuries. The two assassinations took place at a reception of the National Indian Association being held at the Imperial Institute. Varma justified the assassination in his journal The Indian Sociologist arguing that political assassination was not murder. Savarkar, who was also a fellow at India House, glorified his act and martyrdom. Dhingra was tried and sent to the gallows in September 1909. Soon, Martyr Dhingra scholarships were instituted. Gandhi was deeply affected by these murders. In a letter to his friend Henry Polak, Gandhi wrote that those who incited Dhingra deserved to be punished more than the young man himself. In his notes written thereafter, Gandhi emphasized that such acts of terrorism were not only acts of cowardice but that these could never profit India. Even if India were liberated from British rule through violence and murders, independent India would then be ruled by these murderers. White murderers would be substituted by Black ones – he concluded (CWMG 9:428-9). In the months preceding the assassinations in London, similar acts of terror were being carried out in India against both Indian and British officials. Reflecting on these multiple murders and other acts of revolutionary terrorism, Gandhi had a train of thought that he would set down in the Hind Swaraj hurriedly using the stationery of the ship SS Kildonan Castle on which he was travelling from Southampton to Durban. Perhaps, this explains why he partly wrote the Hind Swaraj with his left hand. Gandhi's views on ahimsa were pragmatic. He was opposed to the cult of martyrdom because it not only incentivized dying but also encouraged killing - including killing oneself. Martyrdom fed into the cycle of violence and more violence. Even the famous self-immolation of the Buddhist monk Thich Qu ng D c on 11 June 1963 in Vietnam against the regime of President Ngô Đình Di m can hardly be viewed as one individual harming oneself alone. A few months later, Vietnam witnessed a coup and the President was assassinated. Wars raged for years in Vietnam thereafter. In May 1931, when the American journalist J A Mills asked Gandhi whether he was willing to die for the cause of Indian independence, he chuckled, smiled and famously responded that it was a bad question (available on YouTube as Gandhi's first motion picture interview). Gandhi was influenced by many doctrines of ahimsa, especially from Jainism, through Raychandbhai, who was born into a mixed family of Vaishnavites and Jains. Gandhi's faith in ahimsa compelled him to reinterpret the Gita - a text that rationalized just war. In his lectures on the Gita at Sabarmati Ashram in 1926, he wondered how much better it would have been if Vyasa had not opted for war to illustrate the significance of duty. During those lectures, he was reminded of his discussions with Varma and Savarkar twenty years earlier in London. Both of them had told him that the Gita preached the opposite of Gandhi's own interpretation. But the Buddhist scholar Dharmanand Kosambi opened a window for Gandhi. He advised him to leave textual interpretation to scholars and instead urged Gandhi to demonstrate through action the significance of ahimsa. The Mahatma seems to have done just that. A hundred years ago, all Indian revolutionaries based in London believed that India could not be liberated from English rule except through violence. Gandhi’s arrival on the political scene became a turning point. His influence upon the Indian National Movement altered the nature of the freedom struggle. It became a substantially non-violent people’s movement. The practice of non-violence gained greater traction when it was successfully employed by the Danes against the occupying Nazi forces between 1940 and 1944. Even the Germans successfully employed non-violent resistance against the Nazi regime on Rose Street in Berlin (1943). Gandhi’s ahimsa also offered hope to Gustav Kleinmann, a Jewish upholsterer from Vienna who was incarcerated by the Nazis. During the five years of starvation that he endured inside the concentration camp, his inspiration was Gandhi. Jeremy Dronfield cites Kleinmann in The boy who followed his father into Auschwitz: “I take Gandhi, the Indian freedom fighter, as my model. He is so thin and yet lives.” Courtesy: The article has been adapted from Gandhi Marg, Volume 42 Number 3, October-December 2020 1. Hari Nair is Assistant Professor, Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Birla Institute of Technology and Science, Pilani, Rajasthan 333031. |