DESMOND MPILO TUTU: A great follower of Mahatma Gandhi |

- Ram Ponnu*“...when you discover that apartheid sought to mislead people into believing that what gave value to human beings was a biological irrelevance, really, skin colour or ethnicity, and you saw how the scriptures say it is because we are created in the image of God, that each one of us is a God-carrier. No matter what our physical circumstances may be, no matter how awful, no matter how deprived you could be, it doesn't take away from you this intrinsic worth.” - Desmond Tutu

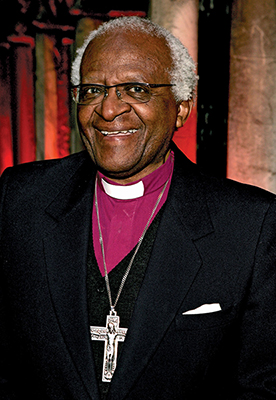

Archbishop Desmond Tutu Archbishop Desmond Tutu is a renowned South African Anglican cleric, a social rights activist and leading spokesman for nonviolence in South Africa. He is considered a “voice for the voiceless” as declared by late President Nelson Mandela. Desmond Tutu was the first black South African Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town, South Africa. An outspoken defender of human rights and campaigner for the oppressed, Desmond Tutu’s eloquent advocacy and brave leadership led to the end of South African apartheid in 1993 and the installation of Nelson Mandela as the nation’s first black President. Tutu became the second South African to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1983 for his nonviolent opposition to apartheid in South Africa. Tutu is the great disciple of Mahatma Gandhi absorbed the moral and strategic power of his nonviolence credo and courageously applied it to change history in South Africa. He remains a charismatic leader and South Africa's premier symbol of moral authority. Tutu later chaired the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the official body that brought to light the atrocities of apartheid on both sides, hoping truth would heal bitterness. Early LifeDesmond Mpilo Tutu was born to Zachariah, a high school headmaster and Aletha Matlhare who worked as a domestic worker, in Klerksdorp, a small town in the Western Transvaal (now North West Province), South Africa on 7 October 1931. The family moved to Johannesburg when he was 12, and he attended Johannesburg Bantu High School. Although he had planned to become a physician, his parents could not afford to send him to medical school. He began his secondary education in 1945 in Western High near Sophia town, around the time he met Father Trevor Huddleston, who would become instrumental in his religious upbringing.1 In 1948, the National Party won control of the government and codified the nation's long-present segregation and inequality into the official, rigid policy of apartheid. At the end of 1950, he passed the Joint Matriculation Board examination, studying into the night by candlelight. He decided to follow his father’s example and become a teacher. In 1951, he enrolled at the Bantu Normal College, outside Pretoria, to study for a teacher’s diploma, completed in 1954 He first followed in his father's footsteps as a teacher at his old school, Madipane High in Krugersdorp, but abandoned that career after the passage of the 1953 Bantu Education Act, a law that lowered the standards of education for black South Africans to ensure that they only learned what was necessary for a life of servitude. The act enforced separation of races in all educational institutions.2 The government spent one-tenth as much money on the education of a black student as on the education of a white one, and Tutu's classes were highly overcrowded. Tutu himself trained as a teacher at Pretoria Bantu Normal College, and graduated from the University of South Africa in 1954. In 1955, he obtained a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Africa (UNISA). One of the people that helped him with his University studies was Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe, the first president of the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC). After his marriage with Nomalizo Leah Shenxane on 2 July 1955, Tutu began his teaching at Munsieville High School, where his father was still the headmaster. He thought hard about joining the priesthood and offered himself to the Bishop of Johannesburg to become a priest. By 1955 he had been admitted as a sub-Deacon at Krugersdorp. No longer willing to participate in an educational system explicitly designed to promote inequality, he quit teaching in 1957. In 1958, Tutu enrolled at St. Peter's Theological College in Rosettenville. He was awarded licentiate of Theology with two distinctions. He was ordained as a deacon in December 1960 at St Mary’s Cathedral, Johannesburg and took up his first curacy at St Albans Church in Benoni location. At the end of 1961, Tutu was ordained as a priest, following which he was transferred to a new church in Thokoza. In 1962, Tutu left South Africa to pursue further theological studies in London where was an exhilarating experience for the Tutu family after the suffocation of life under apartheid. Tutu received his PG Degree in Theology from King's College in 1966. He then returned to teach at the Federal Theological Seminary at Alice in the Eastern Cape as well as to serve as the chaplain of the University of Fort Hare. At Alice Tutu began making his views against apartheid known. When the students at the Seminary went on protest against racist education, Tutu identified with their cause.3 In 1970, Tutu moved to the University of Botswana, Lesotho and Swaziland in Roma to serve as a lecturer in Theology. Two years later, he decided to move back to England to accept his appointment as the associate director of the Theological Education Fund of the World Council of Churches in Kent. Tutu's rise to international prominence began when he became the first black person to be appointed the Anglican dean of Johannesburg in 1975. It was in this position that he emerged as one of the most prominent and eloquent voices in the South African anti-apartheid movement, especially important considering that many of the movement's prominent leaders were imprisoned or in exile.4 Following this, Tutu was persuaded to accept the position of Bishop of Lesotho. After much consultation with his family and church colleagues, he accepted and on 11 July 1976, he was consecrated as Bishop of Lesotho. Whilst in Lesotho, he did not hesitate to criticise the unelected Government of the day. In 1978 he was the first black to hold the position of Dean of St. Mary's Cathedral in Johannesburg.5 He continued to use his elevated position in the South African religious hierarchy to advocate for an end to apartheid. "So, I never doubted that ultimately we were going to be free, because ultimately I knew there was no way in which a lie could prevail over the truth, darkness over light, death over life," he said.6 The South African Council of Churches is a contact organization for the churches of South Africa and functions as a national committee for the World Council of Churches. About 80 percent of their members are black, and they now dominate the leading positions. During this time, Tutu gained International recognition for his vocalization against racial apartheid. Tutu wrote a letter to the South African Prime Minister warning him that a failure to quickly redress racial inequality could have dire consequences, but his letter was ignored. He wrote to the Prime Ministers of Zimbabwe, Lesotho and Swaziland and the Presidents of Botswana and Mozambique thanking them for hosting South African refugees and appealing to them not to return any refugee back to the South Africa.7 In the year of 1979 black workers were able to form unions. The United Democratic Front otherwise known as UDF had nearly 600 members in their organization. The UDF was formed to stop apartheid. Tutu was one of the Front's prime spokesmen. In March 1980, the Government withdrew Tutu’s passport. This prevented him from travelling overseas to accept awards that were being bestowed upon him. He was the first person to be awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Ruhr, West Germany, but was unable to travel, being denied a passport. In September 1982, after eighteen months without a passport, he was issued with a limited ‘travel document’.8 Again, he and his wife travelled to America. At the same time many people lobbied to for the return of Tutu's passport, including George Bush, then Vice President of the United States of America. Tutu was able to educate Americans about Nelson Mandela and Oliver Tambo, of whom most Americans were ignorant. At the same time, he was able to raise funds for numerous projects in which he was involved. During his visit to the States, Tutu addressed the United Nations Security Council on the situation in South Africa. On 7 August 1980, Tutu and a delegation of church leaders and the SACC met with Prime Minister PW Botha and his Cabinet delegation. It was a historic meeting in that it was the first time a Black leader, outside the system, talked with a White government leader. However, nothing came of this meeting as the Government maintained its intransigent position. He earned the wrath of White South Africa when he said that there would be a Black Prime Minister within the next five to ten years. In 1981, Tutu became the Rector of St Augustine’s Church in Orlando West, Soweto. As early as 1982 he wrote to the Prime Minster of Israel appealing to him to stop bombing Beirut; while at the same time he wrote to Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat, calling on him to exercise ‘a greater realism regarding Israel’s existence’.9 Anti-Apartheid activismTutu worked to end South Africa's strict racial segregation policy, known as apartheid. Apartheid means an official policy of racial segregation formerly practiced in the Republic of South Africa, involving political, legal, and economic discrimination against non-whites. Tutu describes the apartheid system as "evil and unchristian." Desmond Tutu formulated his objectives for a democratic and just society without racial division and for everyone to have equal rights. He set forward these following points: the abolition of South Africa's passport laws, a common system of education, the cessation of forced deportation from South Africa to the so-called "homelands" and equal rights. Tutu was also harsh in his criticism of the violent tactics of some anti-apartheid groups such as the African National Congress and denounced terrorism and communism. In the same year, when the people of Mogopa, a small village in the then Western Transvaal were to be removed from their ancestral lands to the homeland of Bophuthatswana and their homes destroyed, he phoned church leaders and arranged an all-night vigil at which Dr Allan Boesak and priests participated.10 In 1983 Tutu had a private audience with the Pope where he discussed the situation in South Africa. When a new constitution was proposed for South Africa in 1983 to defend against the anti-apartheid movement, Tutu attended the launch of the National Forum, an umbrella body of Black Consciousness groups and the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC). In August 1983, he was elected Patron of the United Democratic Front (UDF). Tutu’s anti-apartheid and community activism was complemented by that of his wife Leah. She championed the cause for better working conditions for domestic workers in South Africa. In the same year, he helped found the South African Domestic Workers Association. On 18 October 1984, whilst in America, Tutu learnt that he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize award for his untiring effort in calling for an end to White minority rule in South Africa, the unbanning of liberation organisations and the release of political prisoners. The actual award took place at the University of Oslo, Norway on 10 December 1984. While several Black South Africans celebrated this prestigious award, the Government was silent, not even congratulating Tutu on his achievement.11 On November 1984, Tutu learnt that was elected as the Bishop of Johannesburg. At the same time his detractors, mainly Whites (and a few Blacks e.g. Lennox Sebe, leader of the Ciskei) were not happy at his election. He spent eighteen months in this post before being finally enthroned as Bishop in 1985. His 1986 fundraising tour to America was widely reported on by the South African press, often out of context, especially his call on Western Government to support the banned African National Congress (ANC), a dangerous thing to do in those times. On 7 September 1986, Tutu was ordained as the Archbishop of Cape Town becoming the first Black person to lead the Anglican Church of the Province of Southern Africa.12 In 1987, he was also named the president of the All Africa Conference of Churches, a position he held until 1997. This position provided a national platform to Archbishop Tutu for denouncing the apartheid system as "evil and unchristian" as he called for equal rights for all South Africans and a system of common education. In 1990, Tutu and the ex-Vice Chancellor of the University of the Western Cape Prof. Jakes Gerwel founded the Desmond Tutu Educational Trust to fund developmental programmes in tertiary education and to provide capacity building at 17 historically disadvantaged institutions. Tutu's work as a mediator in order to prevent all-out racial war was evident at the funeral of South African Communist Party leader Chris Hani in 1993. Tutu spurred a crowd of 120,000 to repeat after him the chants, over and over: "We will be free!", "All of us!", "Black and white together!" and finished his speech saying: "We are the rainbow people of God! We are unstoppable! Nobody can stop us on our march to victory! No one, no guns, nothing! Nothing will stop us, for we are moving to freedom! We are moving to freedom and nobody can stop us! For God is on our side!"13 Truth and Reconciliation CommissionIn no small part due to Tutu's eloquent advocacy and brave leadership, in 1993 South African apartheid finally came to an end, and in 1994 South Africans elected Nelson Mandela as their first black president. The honour of introducing the new president to the nation fell to the archbishop.14 After the country’s first multi-racial elections in 1994, the most important domestic agency created during Mandela’s presidency was the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). This commission played a crucial role in South Africa’s journey towards freedom and democracy. President Mandela appointed Archbishop Tutu to chair the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, investigating the human rights violations of the previous 34 years, committed by both sides in the struggle over apartheid. Tutu retired as the Archbishop of Cape Town in 1996 in order to devote all his time to the work of the TRC. The Commission underscored the fact that the process of reconciliation is not about forgetting the past but about acknowledging the crimes committed and thereby acknowledging the other person as a human being who had suffered. The perpetrators of crimes relating to human rights violations who gave testimony were given the opportunity to request amnesty from prosecution. The mandate of the Commission was to bear witness to, record and in some cases, grant amnesty and reparation as well as promote rehabilitation. This process was heavily influenced by the traditional practices of Ubuntu societies in South Africa. Ubuntu is really a quality that Gandhi came to share with progressive Africa. It is our sense of connectedness, our sense that my humanity is bound up with your humanity. Tutu himself says: “What dehumanises you, inexorably dehumanises me.” As always, the Archbishop counselled forgiveness and cooperation, rather than revenge for past injustice. The concept of reconciliation and forgiveness as was practiced in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission headed by Archbishop Tutu was influenced by Gandhi. The commission was given the power to grant amnesty to those found to have committed “gross violations of human rights” under extenuating circumstances. The commission released the first five volumes of its final report on October 29, 1998, and the remaining two volumes on March 21, 2003. Applicants not given amnesty were subject to further legal proceedings. It can be noted that out of 7112 petitioners, and 849 were granted amnesty and 5392 people were refused amnesty. A number of applications were withdrawn.15 More recently his principled stance against corruption and abuse of power by a majority black government in South Africa has added credence to his authentic opposition to oppression and exploitation – by all and in all forms. Vices and virtues flourish equally in all cultures and socio-economic groups globally. South Africa has had a black majority government for the past 23 years, yet there is still no peace because injustice continues to reign supreme.16 He was later named as the Archbishop Emeritus. In 1997, Tutu was diagnosed with prostate cancer and underwent successful treatment in America. Despite this ailment, he continued to work with the commission. He subsequently became patron of the South African Prostate Cancer Foundation, which was established in 2007. In 1998 the Desmond Tutu Peace Centre (DTPC) was co-founded by Archbishop Desmond Tutu and Mrs. Leah Tutu. The Centre plays a unique role in building and leveraging the legacy of Archbishop Tutu to enable peace in the world. In 2004 Tutu returned to the United Kingdom to serve as a visiting professor at King’s College. He also spent two years, as Visiting Professor of Theology at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia. He continued to travel extensively across different places and to work for fair causes, in and out of his country. Within South Africa, one of his focal areas has been health issues, particularly HIV/AIDS and TB. In January 2004 the Desmond Tutu HIV Foundation was formally established under the directorship of Prof. Robin Wood and Associate Professor Linda-Gail Bekker. at the University of Cape Town to the pursuit of excellence in research, treatment, training and prevention of HIV and related infections in Southern Africa.17 The Elders

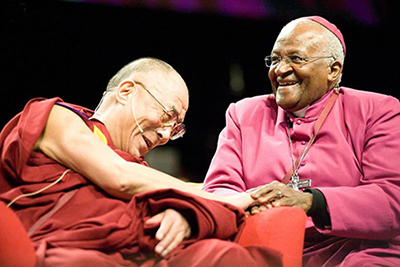

President Obama presenting Tutu with the Congressional Medal of Freedom (August 12,2009) Although he officially retired from public life in the late 1990s, Tutu continues to advocate for social justice and equality across the globe, specifically taking on issues like treatment for tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS prevention, climate change and the right for the terminally ill to die with dignity. In 2007, Tutu joined former South African President Mandela, former U.S. President Jimmy Carter, retired U.N Secretary General Kofi Annan, and former Irish President Mary Robinson to form The Elders, a private initiative mobilizing the experience of senior world leaders outside of the conventional diplomatic process in support of human rights and world peace. Tutu served as chair from 2007 to 2013. Carter and Tutu have travelled together to Darfur, Gaza and Cyprus in an effort to resolve long-standing conflicts. Widely regarded as "South Africa's moral conscience", Desmond Tutu’s historic accomplishments - and his continuing efforts to promote peace in the world - were formally recognized by the United States in 2009, when President Barack Obama named him to receive the nation’s highest civilian honour, the Presidential Medal of Freedom.18 The Government caught on its back foot tried to defend its tardiness. South Africans from across the socio-political spectrum, religious leaders, academics and civil society, united in condemning the Governments actions. In a rare show of fury Tutu launched a blistering attack on the ANC and President Jacob Zuma, venting his anger at the Government’s position regarding the Dalai Lama. The Dalai Lama was previously refused a visa to visit South Africa in 2009. Visibly shaking with anger, Tutu compared the South African government unfavourably with the apartheid regime and threatened to pray for the downfall of the African National Congress. He said: "Our government – representing me! – says it will not support Tibetans being viciously oppressed by China. You, president Zuma and your government, do not represent me. I am warning you, as I warned the [pro-apartheid] nationalists, one day we will pray for the defeat of the ANC government."19 Tutu officially retired from public life on 7 October 2010. However, he continues with his involvement with the Elders and Nobel Laureate Group and his support of the Desmond Tutu Peace Centre. He stepped down from his positions as Chancellor of the University of the Western Cape and as a representative on the UN's advisory committee on the prevention of genocide. Tutu has been prone to health problems related to his prostate cancer. However, notwithstanding his frail health, Tutu continues to be highly revered for his knowledge, views and experience, especially in reconciliation. In July 2014 Tutu stated that he believed a person should have the right to die with dignity, a view he discussed on his 85th birthday in 2016. In an article in the Washington Post, Tutu wrote: ‘I have prepared for my death and have made it clear that I do not wish to be kept alive at all costs. I hope I am treated with compassion and allowed to pass onto the next phase of life’s journey in the manner of my choice’.20 He continues to criticise the South African government over corruption scandals and what he says is their loss of their moral compass. Tutu has never stopped publicly speaking out against what he considers immoral behaviour by various governments from China and its treatment of Tibet, the dissident Yang Jianli, Christians to the United States of America and the War on Terror. In August 2017, Tutu was among ten Nobel Peace Prize laureates who urged Saudi Arabia to stop the executions of 14 young people for participating in the 2011–12 Saudi Arabian protests. In September, Tutu called on Aung San Suu Kyi to end military-led operations against Myanmar’s Rohingya minority, which have driven lakhs of refugees from the country. Tutu said the “unfolding horror” and “ethnic cleansing” in the country’s Rahkine region had forced him to speak out against the woman he admired and considered “a dearly beloved sister”.21 In December, he was among those to condemn U.S. President Donald Trump's decision to officially recognise Jerusalem as Israel's capital despite opposition from the Palestinians; Tutu said that God was weeping at Trump's decision.

Tutu and Dalai Lama Positive ActionIf Nkrumah was successful, he owed part of his formation, directly or indirectly to Mahatma Gandhi. Nkrumah became a disciple of Mahatma Gandhi’s non-violent strategy of Satyagraha, which he coined as “Positive Action.” “Positive action has already achieved remarkable success in the liberation struggle of our continent and I feel sure that it can further save us from the perils of this atomic arrogance. If the direct action that was carried out by the international protest team were to be repeated on a mass scale, or simultaneously from various parts of Africa, the result could be as powerful and as successful as Gandhi’s historic Salt March. We salute Mahatma Gandhi and we remember, in tribute to him that it was in South Africa that his method of non-violence and non-cooperation was first practiced in the struggle against the vicious race discrimination that still plagues that unhappy country. But now positive action with nonviolence, as advocated by us, has found expression in South Africa in the defiance of the oppressive pass laws. This defiance continues in spite of the murder of unarmed men, women, and children by the South African Government. We are sure that the will of the majority will ultimately prevail, for no government can continue to impose its rule in face of the conscious defiance of the overwhelming masses of its people. There is no force, however impregnable, that a united and determined people cannot overcome”.12 In a statement issued in Accra to mark the 56th anniversary of Positive Action declared by the foremost exponent of African unity and the champion of Ghana’s independence struggle, Kwame Nkrumah, the vibrant Leftist group said “Positive Action goes to prove that non-violent means of struggle against an oppressor class is possible and can also be victorious.”13 'Rainbow Nation'Tutu coined the phrase 'Rainbow Nation' to promote harmony among all the peoples of South Africa. The term describe post-apartheid South Africa, after its first fully democratic election in 1994.The phrase was elaborated upon by President Nelson Mandela in his first month of office, when he proclaimed: "Each of us is as intimately attached to the soil of this beautiful country as are the famous jacaranda trees of Pretoria and the mimosa trees of the bushveld – a rainbow nation at peace with itself and the world." South Africa has 11 official languages and may different cultures whose heritage include Malay travellers, indigenous African and Khoi San tribes, Asian emigrants as well as Dutch and British settlers, making it one of the most culturally diverse nations in the world. In a series of televised appearances, Tutu also spoke of the “Rainbow People of God” as within South African indigenous cultures, the rainbow is associated with hope and a bright future.22 The term was intended to encapsulate the unity of multi-culturalism and the coming-together of people of many different nations, in a country once identified with the strict division of white and black. Even though the term's popularity has waned over the years the ideal of a united harmonious South African nation is still one that is yearned for. Desmond Tutu has formulated his objective as “a democratic and just society without racial divisions”, and has set forward the following points as minimum demands:

Nobel Peace PrizeIn recognition of "the courage and heroism shown by black South Africans in their time with the peaceful method of struggle against apartheid" Desmond Tutu received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984. It was "not only as a gesture of support to him and to the South African Council of Churches of which he is leader, but also to all individuals and groups in South Africa who, with their concern for human dignity, fraternity and democracy, incite the admiration of the world," as stated by the award's committee.24 Tutu was the first South African to receive the award since Albert Luthuli in 1960. His receipt of the Nobel Peace Prize transformed South Africa's anti-apartheid movement into a truly international force with deep sympathies all across the globe. The award also elevated Tutu to the status of a renowned world leader whose words immediately brought attention. Other awards given to Desmond Tutu include The Gandhi Peace Prize in 2007, the Albert Schweitzer Prize for Humanitarianism and the Magubela prize for liberty in 1986 and the J. William Fulbright Prize for International Understanding in November 2008. Gandhi Peace Prize"The 2007 Gandhi Peace Prize was awarded to Nobel Laureate and Human Rights Activist Archishop Desmond Mpilo Tutu, in recognition of his invaluable contribution towards social and political transformation and forging equality in South Africa through the Gandhian values of dialogue and tolerance. Tutu is the second South African after Mandela to be honoured with the Gandhi Peace Prize. He has been a tireless and staunch exponent of Mahatma Gandhi's methodology of non–violent action," the citation read. It further said, “Archbishop Desmond Tutu is a rare person who has kept the faith in the efficacy of Truth and Non-Violence alive and inspired hope that in these testing times mankind’s salvation lies in the application of the power of Satyagraha.”25 Archbishop Tutu is a living Gandhian because there has been no greater example of the practice of Gandhiji's principles than the reconciliation effort in post–apartheid South Africa," said then Prime Minister Dr. Manmohan Singh, honouring him. "He wanted the end of British rule in India. He wanted the end of the British Empire. He wanted the end of colonialism. Yet he sought friendship with the people of Britain. It is the same sentiment that Archbishop Desmond Tutu and his comrade–in–arms Nelson Mandela espoused through the institution of the Truth and Reconciliation Council. They fought for the end of apartheid. But they also fought to live in peace with all races, all religions and all communities. There is no better example of Gandhism than this." In his address, Singh described Tutu as a follower of Mahatma Gandhi's vision that "South Africa can boast of proudly". Singh said, "Gandhiji would be elated to see the fulfilment of his aspirations for peace and reconciliation in the transformation South Africa underwent under the leadership of Madiba (Mandela), on whom, in the eyes of the world, the mantle of the Mahatma seemed to have descended."26 Hailing Mahatma Gandhi's ideology of non-violence, Tutu said it was as relevant today as hundred years ago and emphasised that 'practices of injustice' can never have the last word. "By honouring this noble human being with the Gandhi Peace Prize in this historic year of the centenary of the birth of Satyagraha, India acknowledges her debt to South Africa for helping a young lawyer find his moorings and take him to the heights of becoming a Mahatma – a great soul. Like Mahatma Gandhi, Archbishop Tutu, too, became the 'voice of the voiceless,'" it said. Hailing Mahatma Gandhi's ideology of non-violence, Tutu said it was as relevant today as hundred years ago and emphasised that 'practices of injustice' can never have the last word. Human rights activistDesmond Tutu stands among the world's foremost human rights activists. Like Nelson Mandela, Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr., his teachings reach beyond the specific causes for which he advocated to speak for all oppressed peoples' struggles for equality and freedom. He has taught the world to embrace the concepts of “human invaluableness” and interdependence inherent in the phrase "Umuntu ngamuntu ngabantu" – we derive our humanity by virtue of being members of the human tribe.27 Ubuntu theology is Tutu's Christian perception of the African Ubuntu philosophy that recognizes the humanity of a person through a person's relationship with other persons. Drawing from his Christian faith, Tutu theologizes Ubuntu by a model of forgiveness in which human dignity and identity are drawn from the image of the triune God. Human beings are called to be persons because they are created in the image of God. An ubuntu ethic is often expressed with the maxim, ‘A person is a person through other persons’.28 Perhaps what makes Tutu so inspirational and universal a figure is his unshakable optimism in the face of overwhelming odds and his limitless faith in the ability of human beings to do good. "Despite all of the ghastliness in the world, human beings are made for goodness," he once said. "The ones that are held in high regard are not militarily powerful, nor even economically prosperous. They have a commitment to try and make the world a better place." In his human rights work, Tutu formulated his objective as “a democratic and just society without racial divisions,” and set forth demands for its accomplishment, including equal civil rights for all, a common system of education and the cessation of forced deportation.29 Tutu continues to add his voice to global crises where human rights violations are involved. Only recently, in response to the violent persecution of Myanmar’s Rohingya Muslims by the country’s military, he offered this leadership advice to fellow Nobel laureate and Myanmar leader Aung San Suu Kyi: “As we witness the unfolding horror we pray for you to be courageous and resilient again. We pray for you to speak out for justice, human rights and the unity of your people. We pray for you to intervene in the escalating crisis and guide your people back towards the path of righteousness again. It is incongruous for a symbol of righteousness to lead such a country,” said Tutu. “If the political price of your ascension to the highest office in Myanmar is silence, the price is surely too steep”.30 Tutu authored or co-authored several books including The Divine Intention (1982), a collection of lectures; Hope and Suffering (1983), a collection of his sermons; No Future Without Forgiveness (1999), a memoir from his time as head of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission; God Has a Dream: A Vision of Hope for Our Time (2004), a collection of personal reflections; and Made for Goodness: And Why This Makes All the Difference (2010), reflections on his beliefs about human nature. On GandhiIn his Gandhi Lecture on 21 September 2007 at the JMU Convocation Centre, Harrisonburg, Virginia., Tutu recollected the memory of Mahatma Gandhi thus: He spent nearly two decades in South Africa, where he and other people of colour were discriminated against quite harshly with very few political rights. He was thrown off a train because he sat in a whites-only first-class compartment, even though he had paid the fare. Am I glad that he suffered this great indignity, he, a London-trained lawyer? I am glad because it aroused a righteous anger in him and provoked him to develop his Satyagraha methods of nonviolent resistance. He honed the methods in South Africa as he campaigned non-violently to improve the lot of his fellow Indians. Then he returned to his motherland, India, which was ruled as a colony by the British Raj. Mahatma, the great soul, galvanized his people and took on the might of the British Empire. This slight figure, a slip of a man in his quaint garb, took on the British Raj without resorting to violence and prevailed. Independence came for India. Freedom and democracy prevailed where previously the hegemony of a colonial power had ruled the roost. “Goodness is Powerful”.31 NonviolenceMahatma Gandhi’s contribution lies in presenting for acceptance Truth (satya) and Ahimsa in every walk of life. He preached and practised ahimsa to achieve his goal, satya. He campaigned to uplift the downtrodden, to ease poverty, expand woman’s rights, build religious and ethnic amity and to end untouchability. He became the source of inspiration for the leaders and thinkers all over the world. Tutu is also deeply personally committed to nonviolence, and has shown extraordinary personal courage in its service. Tutu’s nonviolence wasn’t simply a political strategy; it was a spiritual practice. It was rooted in this practice of praying for others.32 At least twice he has risked his life to save a suspected informer from a murderous mob. In Daveyton, he stood alone between black demonstrators and heavily armoured South African troops and negotiated a solution that averted certain violence. Tutu’s nonviolence, however, seems more a personal choice. He said, “I wouldn’t, myself, carry guns or fight and kill. But I would be there to minister to people who thought they had no alternative.” Asked whether there is any justification for violence, he replied, “If I were young … I would have rejected Bishop Tutu long ago.”33 Despite bloody violations committed against the black population, as in the Sharpeville massacre of 1961 and the Soweto rising in 1976, Tutu adhered to his nonviolent line. To conclude, Tutu became South Africa's most well-known opponent of apartheid, that country's system of racial discrimination, or the separation of people by skin colour. Despite bloody violations committed against the black population in South Africa during Apartheid, Tutu adhered to his nonviolent line. Since, he has emerged as a global voice for peace, reconciliation and social justice.in the transition to democracy, Tutu was an influential figure in promoting the concept of and reconciliation, redemption and forgiveness. For Tutu, this was a divine mission for reconciliation to be forged out of seemingly intractable conflict. Tutu has been recognised as the ‘moral conscience of South Africa’ and frequently speaks up on issues of justice and peace. Tutu has become an icon far beyond the church, and far beyond South Africa’s borders, and has been hailed for his outspokenness, fearless attitude and forthright opinions. Works Cited

* Principal (Retd.), Kamarajar Govts. Arts College, Surandai, Tirunelveli Dist., Tamil Nadu. Email: eraponnu@gmail.com |