Some men changed their times...

One man changed the World for all times!

Comprehensive Website on the life and works of

Mahatma Gandhi

+91-23872061

+91-9022483828

info@mkgandhi.org

+91-23872061

+91-9022483828

info@mkgandhi.org

Dialectics of Gandhi and Ambedkar |

- Dr. D. John Chelladurai

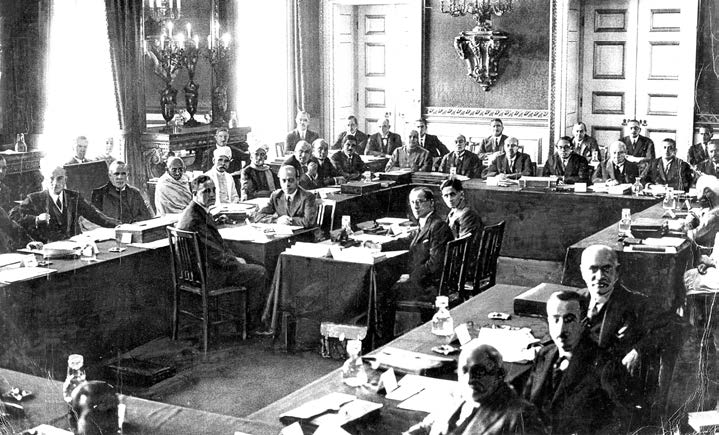

Mahatma Gandhi at the Federal Structure Sub-Committee meeting presided over by Lord Sankey, at St. James' Palace, London, November 24, 1931. Among those present were Pundit Madan Mohan Malaviya, Srinivas Shastri and Dr. B. R. Ambedkar. The Indian nation building process which began with the struggle for independence, witnessed quite a few momentous discourses. The one between Gandhi and Ambedkar was notable among them, for it dealt with one of the most sensitive issues of social liberation, and to that extent continues to intrigue common readers. Opinion is divided between the Gandhians and Ambidkarites, each arguing in favor of one and more emphatically against the other. The apparent confrontation between both the leaders, when subjected to objective analysis however reveals the fact that, it represented a much awaited pang of the birth of a new social order that was struggling to gain new life. The major discord, which of late assumed the proportion of controversy, came up in 1932, when Gandhi undertook infinite fasting against the separate electorate ordinance. The year before, during the Second Round Table Conference, the representatives of the depressed classes joined hands with other minorities (Muslims and Sikh) and demanded separate electorates provision for minorities, including for those who were denigrated as ‘untouchables’. The Premier, Ramsay MacDonald in his speech on the 13th of November 1931 in the minority’s sub-committee, officially blessed the demand. Gandhi then contemned it as a sinister design. Gandhi who had personally suffered humiliating racial discrimination in South Africa (thrown out of train; denied of passage on major streets, called as ‘coolie’ Barrister), had declared himself as an ‘untouchable’ by choice.1 Terming this inhuman practice as a curse on Hindusim, he committed himself right from the beginning of his public life for the removal of ‘untouchability’. Inducting a harijan family (of Dudabhai, Daniben, Laxmi) in his ashram in 1917 ignoring the wrath of his donors,2 was but a small instance in his event filled campaign for social liberation. Gandhi condemned the practice of ‘untouchability’ as no one else did in his league. He equated the practitioners of the ‘crime of untouchability’ with the homicidal Gen. Dyer. “Have we not practiced Dyerism and O' Dwyerism on our own kith and kin?3 he asked; and termed the ‘colonial subjugation’ that Indians suffered as the reward for the untouchability practiced by Indians. “Have we not reaped as we have sown?” he reminded the nation, “we have segregated the 'Pariah' and we are in turn segregated in the British Colonies.”4 As early as 1921, Gandhi appealed to the conscience of the Hindus. He asked them, “how is this blot on Hinduism to be removed” except by “repenting for the wrong we have done and altering our behavior towards those whom we have suppressed?. We must not throw a few schools at them; we must not adopt the air of superiority towards them. We must treat them as our blood brothers as they are in fact. We must return to them the inheritance which we have robbed them of. It must be a conscious voluntary effort on the part of the masses. We may not wait till eternity for this much belated reformation. We must aim at bringing it about within this year of grace, probation, preparation, and tapasya. It is a reform not to follow Swaraj but to precede it.”5 Gandhi was convinced that this deep rooted social sickness can be cured only through social transformation especially among the orthodox Hindus, whose selfassumed superiority formed the basis of the whole oppression. He felt, that a political move such as the Separate Electorate6 served only to spoil the nation’s fight against ‘untouchability’. His opposition to the Separate Electorate was based on the following major observations: 1) Separate electorate is a divisive electoral procedure. “Instead of citizens voting as citizens” under this provision, “Moslems will vote as Moslems, Hindus as Hindus, women as women, and 'untouchables'7 as 'untouchables',” each choosing their separate MPs and MLAs by a separate election. That would divide India as a whole down to its last village into Dalit India, Muslim India, Sikh India, forever.8 If we are one people, which we are, we must have our common representatives in political governance, Gandhi argued. 2) The British scheme of separate electorates, Gandhi worried, would “kill all prospect of reform”9 and morph 'untouchability' into a “powerful vested interest.” The process that it embodied was “not one of fusion but of balancing of interests and of classwar.”10 3) While ‘Sikh’ and ‘Muslim’ are, for that matter, positive social identities, that may remain in perpetuity, Gandhi pointed out, ‘untouchability’ on the contrary, is a heinous practice and a social stigma,11 that deserves to be summarily buried. Gandhi wrote to Ramsay MacDonald eleven days before the commencement of his fast that, separate electorate for ‘untouchables’ would amount to legally concretizing this shameful identity on a people who deserved justice and equality. “We do not want on our register and on our census ‘untouchables’ classified as a separate class,” Gandhi stated, and “I would not sell the vital interest of the depressed class even for the sake of winning the freedom of India.”12 4) One needs to note, the people whose cause Dr. Ambedkar was fighting for, were then termed as ‘avarnas’. They were not regarded as part of the chaturvarna. That is why they were treated as ‘un-seeable’ ‘un-approachable’13. That was the reason, Gandhi denounced the separate electorate “as an act of Satan” feeding to the “creation of the 'fifth class' in Hinduism”14 He said, “in the establishment of a separate electorate for the Depressed Classes I sense the injection of poison that is calculated to destroy Hinduism15 and do no good whatever to the Depressed Classes."16 5) Gandhij, on his part, wanted a complete dissolution of the bar sinister which separated the 'untouchables' from the Hindu fold. And, he argued that “this shameful practice of untouchability is a blot, not on the 'untouchables', but on the orthodox Hinduism.”17 And he believed, their salvation could come not through the machinery of law but only through conscious introspection, serious soul searching and penance by the caste Hindus.18 And this political “separation would kill all prospect of reform.”19 Hence he declared “My fast is intended to remove this obstacle in the way. It is only a preparation for a living pact between the Caste Hindus and the 'untouchables' that would result in a complete abolition of the 'fifth caste'"20 not from the records alone, but from the hearts of the people. Gandhi spoke to the press on the first day of his fast: “What I want, what I am living for, and what I should delight in dying for, is the eradication of untouchability root and branch. I want, therefore, a living pact whose life-giving effect should be felt not in the distant tomorrow but today, and, therefore, that pact should be sealed by an all-India demonstration of 'touchables' and untouchables meeting together, not by way of a theatrical show, but in real brotherly embrace. It is in order to achieve this, the dream of my life for the past fifty years, that I have entered today the fiery gates… For me the abolition of separate electorates would be but the beginning of the end.”21 ‘Justice and equality for the depressed masses to be ensured not at the earliest but at once’ was an urgency both Gandhi and Ambedkar felt alike. Whereas, being a victim of the dastardly acts of discrimination himself, Ambedkar was desperate to get his people out of this quagmire at once, and not ready to mutely wait for the mercy of the victimizers.22 Ambedkar’s desperate search for a way out led him to seek an exclusive, political approach, which in a situation of crisis, is considered to be the best solution.23 A person caught in a room engulfed by fire would try to come out of it by any means, even breaking the window or door, and not wait for the rescue team to come and open the door, and more so when the ‘fire’ was part of the conspiracy of the very ‘rescue’ team.24 Gandhi with his “irrepressible optimism” proposed an inclusive social cure; he argued that reformation of the orthodox Hindus could be realized within a short span of time, faster than what Dr. Ambedar intended to achieve politically. His claim proved to be true. His selfless fast, did orchestrate a transformation among the oppressors so rapid and instantaneous, it amazed even the staunch critics of Gandhi. On the very first day of Gandhi’s fasting unto death, thousands of Hindu temples including in places like Benares, Allahabad, Bombay, voluntarily opened their doors, first time, for the ‘untouchables’, and hundreds of thousands of orthodox Hindus went to dalit locality in the neighbourhood to dine with them. Reports of dalit non-dalit conversation and social discourses came from all directions. Gandhi’s call for “reform with in this year”, was making great stride.25 Both Ambedkar’s aggressive pursuit of political empowerment of the oppressed, and Gandhi’s intensive attitudinal cleansing voluntarily undertaken by the ‘oppressors’ did equally prove to be magnificent in their impact. Gandhi’s approach was considered to be more holistic and sustainable, for it dealt with the roots of the problem, and evoked voluntary reform. However we learn from history that, such an approach would work only under an enlightening leadership as that of Gandhiji. The slowing down of social transformation post Gandhi era substantiates that apprehension. In such a case, Ambedkar’s aggressive and unilateral claim for equality appears pragmatic and as a pertinent complementary, from the point of view of the oppressed. Indian journey of social justice is invariably a mix of both well-meaning political reformation enforced from the top and an honest social transformation voluntarily undertaken at the grass roots, each vitalizing the other. What happened between Gandhi and Ambedkar, in that sense, was an essential dialectic discourse in the journey of Indian liberation, that synthesised an ever growing brotherhood between people who once were poles apart.

Mahatma Gandhi addressing the people from the train coach outside the station platform during his Harijan tour to South India, February 1946. Reference:

Courtesy: This article has been reproduced from Khoj Gandhiji Ki, a monthly magazine of Gandhi Research Foundation, Jalgaon, Issue 46, December 2021. |