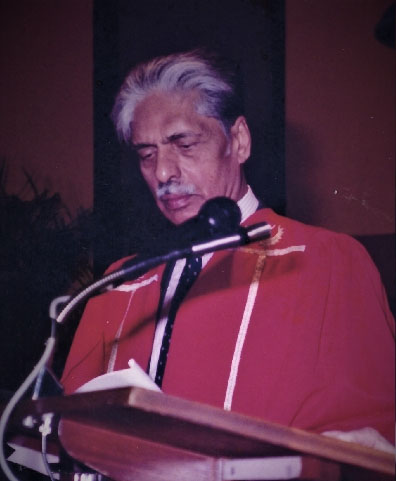

E.S. Reddy, the Gandhi-Reservoir |

- By Ramachandra Guha* A future biographer of E.S. Reddy would demarcate three phases of his life; his childhood and youth in south India, growing up amidst the fervour of the freedom struggle led by Gandhi and the Indian National Congress; his professional work with the United Nations in New York, when he did so much to co-ordinate and direct the international campaign against apartheid, while befriending many South African freedom-fighters in exile, among them the great Oliver Tambo; and his life after retirement from the UN, when, in his 70s and 80s, he was acknowledged as perhaps the most learned (as well as certainly the most selfless) of Gandhi scholars.

These three phases, were, of course, overlapping; with the Indian patriot influencing his work as an anti-apartheid campaigner and both deeply informing the research he did and the books he wrote on Gandhi and his legacy. I myself got to know Mr Reddy some years after he had retired from the UN, and was now devoting himself more or less full-time to Gandhi. In the late 1990s I visited New York, and my friend Gopal Gandhi gave me a letter of introduction to E.S. Reddy, while describing him to me as a ‘Gandhi-reservoir’. Mr Reddy lived in a small flat in midtown Manhattan, with his Turkish wife Nilufer, who was herself a translator of the poet Nazim Hikmet. They received me warmly, and we talked about matters Indian and South African. At this time, I was merely interested in rather than obsessed with Gandhi. But within a few years I was seeing myself as a ‘Gandhi scholar’. Whenever I was in New York I would visit that flat on 46th Street; in between visits, I kept up a steady correspondence with Mr Reddy, asking questions and being sent answers as well as attachments in return. Enuga Reddy was one of God’s good men: soft-spoken, self-effacing, and utterly committed to decency in public as well as private life. I felt specially favoured, as doubtless others who had made the trek to his door also did. For I was one of many beneficiaries of his wisdom and his generosity. He saw Gandhi not as his private property but as belonging to the world and to the ages. Whatever he had, he shared and passed on. In this tribute, I’d like to reproduce snatches of my correspondence with him, to seek to demonstrate what kind of scholar and human being he was. Let me begin with an exchange we had in August 2010, when he was preparing to go to South Africa to receive an award bestowed upon him by the Gandhi Development Trust in Durban. ‘It is a short trip,’ he wrote to me, ‘and I do not know how much I can do, and how many of my friends I can meet, after the long flight from New York.’ I replied: ‘It is wonderful to know you are going to South Africa, and many congratulations on the award. You are a South African democrat, an Indian patriot, and a citizen of the world.’ E.S. Reddy had been to South Africa once before, shortly after Nelson Mandela was released. At that time, during his second trip to that country, he was in his mid-80s. After receiving the award that he so richly deserved – few foreigners had contributed as much to the South African struggle for freedom, and certainly no Indian – Mr Reddy wrote this letter to two friends in his own homeland: Dear Gopal and Ram, To this I replied: Dear Mr. Reddy, His trip to South Africa made Mr Reddy determined to write a short book about the Indians who had participated in the satyagrahas that Gandhi had led in South Africa. A letter dated October 16, 2010 thus informed me: I have been looking at some issues of Indian Opinion for the period of the satyagraha. I thought of preparing a list of satyagrahis, expanding the small list I had prepared mainly from CWMG. That task is impossible as there are many variations in the spellings of names, and many last names without first names etc. While I was encouraging my octogenarian mentor to get going with this historical project, other friends were chastising him for not writing about his own role in the struggle to end apartheid. In January 2011, after sending me some rare clippings, he wrote to me: ‘As you may have guessed I have been going through Indian Opinion, 1903-14. Ela Gandhi scolded me for wasting my time on what others can do (presumably South Africans) instead of writing my memoirs about UN and anti-apartheid, but I could not stop. That took me many days and I have made many photocopies.’ The letter continued: ‘My intention was to prepare a list of Satyagrahis, based mainly on Indian Opinion, though that will be only a fraction of the satyagrahis. And to prepare a Who’s Who of satyagrahis on whom biographical information is available. I do not know whether I will be able to do this, as it is a time-consuming task. I will see. In the meantime, I have gained a better perspective on the Satyagraha.’ I wrote back a letter of solidarity and support. ‘In research, one must follow one’s instincts and not those of friends, however esteemed they may be!,’ I told hi’: ‘The clippings on the ANC and Dube are utterly fascinating. And the work on Satyagrahis will be invaluable.’ In August 2011, eleven months after he had returned from accepting that award in Durban, he sent me this update on the progress of his latest research project: Dear Ram, It was, of course, an absolute privilege to do just once for Mr. Reddy what he had done so regularly for me – offer advice on a piece of research. I read and commented on a draft, and the book was eventually published by Gandhi’s own publishers, Navajivan Press, with the title Pioneers of Satyagraha: Indian South Africans Defy Racial Laws, 1904-1914, and under the joint authorship of E. S. Reddy and the South African historian Kalpana Hiralal. Mr Reddy had, as several of the contributors to this volume would know, an incredibly detailed knowledge of the minutiae of Gandhi’s life and campaigns, which was freely given to and eagerly drawn upon by greedy scholars from across the world. But beyond this command over the facts, he also had a deep, indeed, profound, understanding of Gandhi’s character and personality. This was illustrated in an exchange we had in June 2011, over a newspaper column where I had contrasted Gandhi with the publicity-crazy holy men of our own time. I had focused in particular on Baba Ramdev, who had recently gone on a hunger-fast against corruption in New Delhi but fled when the police arrived at the venue. My column began with this vignette from the past: ‘There is a photograph of the Second Round Table Conference in London, which shows every person in the room looking at the camera except for Mohandas K. Gandhi. The Maharajas, the leaders of the Depressed Classes and the Muslim League, the officers of His Majesty’s Government, all have their face turned at the photographer come to capture them. Not Gandhi, who sits in his chair, wrapped in a shawl, looking downwards at the table, waiting for the tamasha to end and the discussion on India’s political future to resume.’ I said of Gandhi that he was a politician and social reformer to whom ‘the moral and spiritual life was equally important’. However, unlike his political activism his moral quest was undertaken not in public but in the privacy of his own ashram. For Gandhi, solitude and spirituality went hand-in-hand. Thus, in between his campaigns, he spent months at a stretch in his ashrams at Sabarmati and Sevagram, thinking, searching, spinning. On the other hand, I wrote, ‘Our contemporary gurus cannot be by themselves for a single day. When the police forced him out of Delhi, Ramdev said he would resume his “satyagraha” (sic) at his ashram in Haridwar. But within twenty-hours he left Haridwar, in search of closer proximity to his brothers in the media. Externed from Delhi, Ramdev knew that many television channels were headquartered in NOIDA. So he would go to them, since he knew that, despite their national pretensions, these channels would not send their reporters, still less their anchors, to the benighted state of Uttarakhand.’ As always (because Gandhi was mentioned) Mr Reddy read the column not long after it appeared, and sent me a long, meditative, note about it. He did not dispute my saying that people like Ramdev belonged to the history of publicity rather than the history of spirituality. But, he added, ‘I have difficulties with what you imply about Gandhi.’ His own understanding of the Mahatma’s spirituality he outlined as follows: Gandhi did not pose for photographs. He gave permission to three sculptors, while in London (1931) but did not ‘pose’ for them. He was at work and they were allowed to be in the room. Mr Reddy and I had the occasional disagreement. One I’d like to recall here was with regard an essay on Gandhi’s legacy in South Africa, a draft of which I had naturally sent to the world’s greatest expert on the subject. Mr Reddy liked the essay on the whole, remarking: ‘You read so many books in your research, some I haven’t. I am a slow reader.’ Then he added: ‘But you made a terrible blunder in the last clause of your last sentence.’ What was my alleged blunder? This was to claim that ‘Gandhi had no interest in sports at all’. To rebut this Mr Reddy wrote: ‘Gandhi was chairman of the Indian football clubs in Durban and Johannesburg. He organized a football match in Tolstoy Farm. I believe he was also chairman of a cricket club. I have not read about his playing sports, but he used to bicycle in Johannesburg instead of renting a carriage — a barrister!’ Mr Reddy’s letter of chastisement continued: I remembered that a first page of Indian Opinion in 1914 had an article on Gandhi and Sports. To find it I went to the index to Indian Opinion in the DVD and searched for ‘sport’. Here are the results. (If I had searched for football and cricket, I might have found more results. I suppose you have the DVDs from Gandhi Museum.) From this list of index entries, Mr Reddy said, ‘It looks like he [Gandhi] started protesting segregated sports. Then he is way ahead of his time. After the [second world] war, Indians in South Africa started a movement against racial segregation on sports. That developed into an enormous movement for boycott of apartheid sports, which played a key role in the struggle for liberation. Sam Ramsamy, chairman of SAN-ROC was a key figure in the sports boycott movement. It is his 75th birthday today — being celebrated in Durban. I did quite a bit in that movement and I sent a message to the meeting last night.’ The letter ended with my mentor urging me: ‘You should make up for your mistake by writing a column on Gandhi and sports. Otherwise, I will write an article later this year. But I have trouble publishing my articles, while you can reach a large audience.’ Now sport was a subject I knew something about. I had spent much of my youth playing cricket, and had later written several books on the sport. So I wrote to Mr Reddy now saying that ‘I must (perhaps for the first time!) enter into an argument or disagreement! You are right about Gandhi’s chairmanship of clubs for Tamil footballers, but this was done out of social obligation, not love of sport.’ The Tamils in South Africa were passionate football players, and had thus invited their admired leader to be a patron of sporting clubs in Durban and Johannesburg. But, I told Reddy, ‘Gandhi accepted – out of affection (and admiration) for the Tamils, not love of sport per se. So far as I can tell, Gandhi did not (unlike Mandela and even Nehru) spontaneously or voluntarily play or watch sports after he left school.’ Mr Reddy was not going to back down so easily. So he responded: ‘What I want to say is that he recognised the importance of sport. He did not play football, but organized football matches. He may perhaps be regarded as a sports administrator in his younger days in South Africa.’ And further: ‘He was fond of walking and did bicycling. Isn’t that also a sport? I wonder, as I walk a little for my health on doctor’s orders.’ And further still: ‘Then he raised the question of segregation in sport. I admit that is not a question of sport but of public policy. I was excited to read about that as it links with my own work against apartheid sport.’ Mr Reddy ended his letter with a concession, writing that ‘I agree walking for health or bicycling to work is not sport. So we have very little disagreement left. Let it be a little as I want to write about segregation in sport in South Africa.’ To this I answered: ‘Thanks – in my social history of Indian cricket I have a chapter on Gandhi’s opposition to communally organized sport, consistent with his opposition to segregated sport in S[outh] A[frica].’ Having slept over the matter, however, Mr Reddy woke up with the feeling that he did have a substantive disagreement with me after all. So now he wrote a fresh mail, saying: “What bothered me was your ‘no interest in sports at all’. Couldn‘t one be interested in cricket – mad about cricket – without playing cricket. Gandhi thought sports was good. He was associated with sports bodies. He encouraged sports competitions. He may have done this even in the 1890 s when he was trying to help the colonial-born educated boys to advance.” Mr Reddy thought Gandhi did have an interest in sport, ‘but he had no time for playing sports as he wanted to devote 24 hours a day to his preoccupation or obsession of service to the community. I still do not have a different word to suggest. That is up to you.’ He then offered his own personal experience to persuade me to consider the matter more sympathetically from Gandhi’s own perspective. So he wrote, ‘For most of my life, especially since I was appointed secretary of the committee against apartheid, I was obsessed. I worked almost every night, every weekend, gave up half my leave and carried work in the other half. As a result I lost my love of poetry, of movies and other things. I did not even think of sports – I was never good at that any way. I am not proud of all this. I was not a good administrator, did not know how to delegate.’ While Mr Reddy lost interest in all these things, he insisted that ‘Gandhi did not lose “interest” in sports, I believe, until he left South Africa. He became a different man in India because of the mahatmaship he did not ask for.’ I stuck to my guns, telling Mr Reddy ‘you must allow that in this respect Gandhi really was deficient. You lost your zest for music and poetry because of your obsession with apartheid – I have lost my love of cricket now because of my obsession with Gandhi. But, in truth, the aesthetic side of Gandhi WAS somewhat or massively undeveloped. He was indifferent to art and the beauties of nature (remember, he didn’t let [his son] Manilal climb Table Mountain). His interest in music and sport was largely instrumental (promoting inter-faith harmony)—I think he may even have had a tin ear. He certainly didn’t know how to kick a ball or hold a bat.’ That Gandhi had deficiencies of course Mr Reddy was prepared to allow. Except that the weaknesses he pointed to were weightier than the ones I had identified. The correspondence concluded with the 88-year-old confiding to me one of his remaining ambitions: ‘I would love to try a book showing what was wrong with Gandhi in his early years in South Africa – racist statements, cruelty to his wife – he even hopes she dies so that he can do his work, patriarchy, etc. – showing how he evolved into a great man but was still deficient. Great men have great weaknesses.’ My correspondence with Mr Reddy was not always on serious matters of historical fact and interpretation. It occasionally had a lighter or more personal side, too. In April 2009 he wrote to me: ‘I miss your columns in The Hindu. Are you busy with your book – leaving cricket to Shashi Tharoor?’ I answered: “Thanks for your kind words re my lapsed Hindu column – but, as [the cricketer] Vijay Merchant once sagely remarked, it is better to retire when people ask ‘Why’ rather than ‘Why Not!’ I was getting a little bored with the column, and anyway needed space and time to focus on my books – had I still been writing for the Hindu I think you might have thought to yourself, ‘This fellow is repeating himself...'” A year-and-a-half later Mr Reddy had occasion to write saying: ‘You are quoted in two stories in New York Times today – one on illegal mining and another on Kashmir. That is a public intellectual!’ I laconically replied: ‘More like a convenient fall-back guy for confused foreign journalists!’ A general election was due in India in the summer of 2014. As the campaign intensified, I was interviewed by a news magazine about the two main prime ministerial candidates, Narendra Modi of the Bharatiya Janata Party and Rahul Gandhi of the Congress. The magazine carried my remarks under the headline: ‘Rahul a spoilt child and Modi a megalomaniac’, says Ramachandra Guha’. Mr Reddy saw this before I did; sending me the link, he added an approving comment of his own: ‘I suppose now you have the status to take on the imposters, however high.’ In the event, the megalomaniac Narendra Modi became Prime Minister, and his party began to aggressively assert their Hindu majoritarian agenda. In January 2016 Mr Reddy sent me a mail which read: ‘I see you are making statements in lectures and interviews provoking the hindutvaites. That is worthwhile. But do you get any time to work on the second volume of Gandhi biography?’ I answered: ‘I take your caution, and will be more sparing in my public utterances! But I must assure you that I am indeed working on the second volume. I have written some 28 chapters so far, bringing the story up to May 1944. I decided not to burden you with the later draft chapters, since you have several must-be-completed projects on your desk already. Instead, I got the second Gandhi-reservoir, Gopal [Gandhi], to check for howlers and mistakes.’ Mr Reddy replied that I could send him my chapters to read, for, as he noted, ‘I have only three projects as of now. Two need little more work. Third, my reminiscences of anti-apartheid is an endless long-term project which I may not even finish in this lifetime. I am sending drafts to a friend in South Africa so that they can be deposited in a library if I pass away.’ The letter ended: ‘I am, in fact, spending time assisting Gandhi archives in Sabarmati in their ambitious project of transcribing and publishing the letters received by Gandhi, etc.’ Mr Reddy was, at the time of this writing, 91 years of age. In October 2015, Mr Reddy and his wife Nilufer left New York City after living 66 years together in the city. They moved to Cambridge, Mass, where they would stay next to their daughter Mina and her children. Three years later, I was in Cambridge myself, and called on my mentor at his daughter’s home on Mount Auburn Street. Afterwards Mr Reddy wrote to Gopal Gandhi: ‘Ram Guha came to us for tea at short notice (20 minutes). We had a good time.’ Gopal replied, copying me: ‘How wonderful! Lucky him. He has sent me a lovely picture of you, sporting a stylish goatee. A keepsake.’ A year later Mr Reddy and I corresponded about the latest of his book projects. This was an edited anthology of Gandhi’s interviews to Americans. The publisher had taken several years to obtain permissions, and had just sent him the final text. ‘I went through the entire manuscript, 400 pages, this month, and made some revisions,’ he wrote to me, adding: ‘Their editor will now work on it. I hope it will be published soon — in the first half of the year.’ Alas, the publication was further delayed, for in the spring of 2020 the coronavirus pandemic began to wreak its path of devastation across the world. On the May 5, 2020 I wrote to my ninety-five-year-old Gandhi-reservoir, living in the United States, while still holding an Indian passport: Dear Mr Reddy, I received his reply the same day. ‘Thank you for the message,’ wrote Mr Reddy: ‘Happy to hear of life in the Nilgiris. We are doing very well. We do not go out. Our daughter and grandson who live upstairs take good care of us. We manage to read much and write very little.’ That was the last letter I received from Mr Reddy. On August 8, 2020, his daughter Mina wrote to Gopal Gandhi passing on this message to him from her father: ‘He wants you to know that he has entered the last stage of his life and is resting at home with hospice services. My mother and other family are caring for him.’ Gopal wrote back a warm and wonderful mail, of which I might quote some lines that captures the work and legacy of E.S. Reddy far better than I ever could: ‘What a life he has lived, so full of quiet but huge support to great causes, of which South Africa is the best known, and so full too of the highest scholarship. No “trained historian” can do more than he has for resurrecting Gandhi from dull nationalist narratives to his true place in the history of the global emancipations of the oppressed.’ The Wire, dt. 14.5.2022. * Ramachandra Guha, is a historian and biographer based in Bengaluru. His books include Gandhi Before India, which was dedicated to E. S. Reddy. |