Some men changed their times...

One man changed the World for all times!

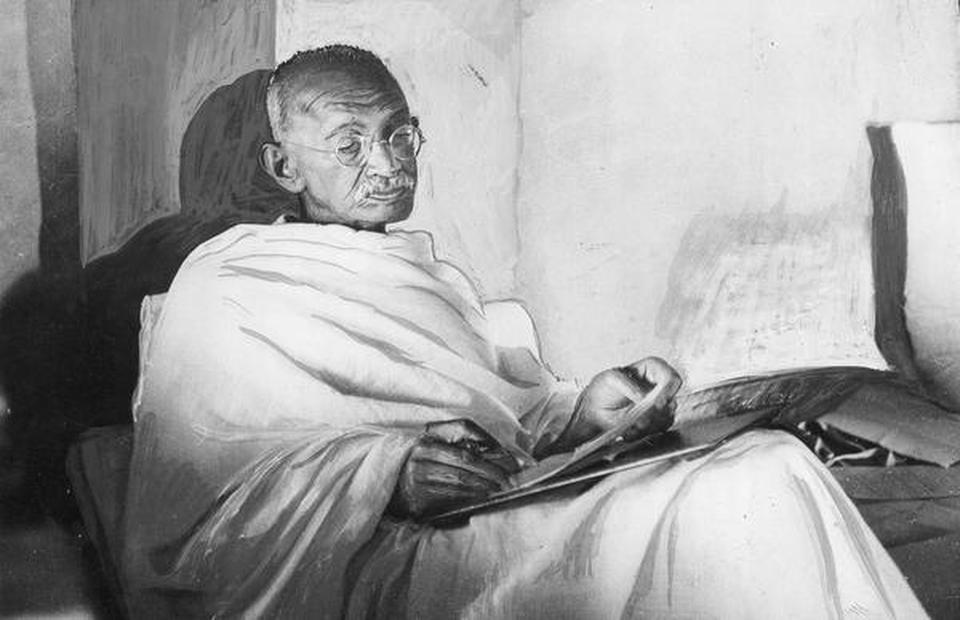

Comprehensive Website on the life and works of

Mahatma Gandhi

+91-23872061

+91-9022483828

info@mkgandhi.org

+91-23872061

+91-9022483828

info@mkgandhi.org

Meals with the MahatmaMK Gandhi was known for keeping indefinite fasts. But he was, interestingly, also one of the first to promote what is now celebrated as ethical eating and superfood. Here’s looking at the Gandhian culinary theory. |

- By Zac O’Yeah*

Photo Credit: HINDU PHOTO ARCHIVES “I have been a cook all my life. I began experimenting with my diet in my student days in London,” said Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi as he lectured residents of the Sevagram Ashram, in present-day Maharashtra, in 1935. He’d just relocated to the India of villages — leaving behind Ahmedabad, his home since his return from South Africa two decades earlier. It was a paradigm shift that he felt strongly about: “Now we have embarked on a mission the like of which we had not undertaken before.” Then, eventually, he got to the point that he wished to make regarding village reforms: “Let us not, like most of them, cook anyhow, eat anyhow, live anyhow. Let us show them the ideal diet.” He proposed that they do away with spices and eat raw food, such as salads, at least once a day while teaching the villagers to do the same, because boiling vegetables destroyed vitamins. Apart from the fact that uncooked food was virtually unheard of in that era, it’s interesting that Gandhi talked about vitamins. Their role in preventing illness and building health had been proposed by a Polish chemist only in the 1910s and it took a while longer before the Nobel Academy recognised the work of vitamin researchers. In the 1920s, Gandhi wrote, “Vitamin means the vital essence. Chemists cannot detect it by analysis. But health experts have been able to feel its absence.” Yet I can’t imagine that everyone who listened to Gandhi that day felt cheerful. No masala in the curry? Uncooked food? I see jaws dropping and eyes popping. Maybe, I suspect, he wasn’t entirely on to the medical benefits of certain flavouring means such as ginger, garlic, cardamom and turmeric, and so he went a bit extreme, but then a pioneer would probably need to do that. This reminds me how, about 20 years ago, on a train from Delhi to Kanyakumari, I broke the journey at Sevagram, Wardha. I had heard that Gandhi had founded his ashram at Sevagram because it lies at the centre of India. It seemed appropriate to get off there. The railway station was empty and I was the sole passenger alighting. The only things moving in the quiet heat were dry leaves rustling before a feeble breeze. Outside stood alone cycle rickshaw. There was no hotel in sight. It was of course an even more unassuming village in the 1930s when Gandhi moved in. He instructed his helpers that ‘as little expense as possible should be incurred’ in building his hut. I approached the rickshaw and, not being conversant in Marathi, I showed a banknote with Gandhi’s image on it. The rickshaw-puller read my mind and took me to the ashram. I had first thought of taking a look at the museum and then carry on to the nearest town, Nagpur, to spend the night. But before I could do so, an elderly resident of the ashram, who had seen me carrying luggage, asked me to follow him. We walked past a pipal tree planted by “Bapu” (Gandhi preferred not to be called Mahatma) and his clay hut. Adjacent to it was the guest house that hosted Jawaharlal Nehru and other political leaders when they came to consult with Gandhi, and I was shown a spacious room to call my own for as long as I liked. The cot was of 1930s vintage, there were no mod-cons and the rent was around Rs. 30/-. I was asked to make myself comfortable and then join them for supper. It was the strangest thing I had ever experienced as a traveller — no one asked who I was or how long I planned to stay. I was simply made to feel at home. This “village of service” turned into a laboratory for Gandhi as it attracted all manner of creative engineers and assorted experts who researched ecological lifestyles, devising everything from lanterns that burned waste vegetable oil instead of fossil fuel to experimenting with education models. Important people who arrived at the station were picked up by what Gandhi jokingly called his “Oxford”, a broken Ford car pulled by oxen. And then there was the alimentary mission. Gandhi was by no means against food, despite his asceticism and frequent fasting to push political agendas. He was merely interested in making the most of a precious resource. For example, later in that first year in Sevagram, he advocated the daily consumption of soya beans, which have marvellous health benefits. He pointed this out in a series of articles in his journal Harijan, describing soya beans as what we today would call a ‘superfood’, one that possibly cures constipation, flatulence, corpulence and diabetes. He introduced novelties such as sugar cane and papaya cultivation, and bee-keeping, which suggests that the sweet tooth wasn’t frowned upon. Under his leadership, the ashram also produced marmalade from seasonal fruits, peanut butter and bread made from home-ground coarse unsifted wheat flour. Gandhi also developed a coffee substitute (he was against caffeine) from dark-roasted wheat. Generally, the fare seems to have been akin to what we’d today encounter at the finest among urban India’s new-fangled organic stores.

Ground rules: Every meal at the Sevagram ashram was a group affair. There was a ban on making conversation while eating. After a bath, I headed for the dining hut at the ashram. The sun hung low on the horizon and meals were strictly timed (dinner at 5.30 pm, as I recall). Meals in the ashram have always been had together. Gandhi kept an eye on how much each person ate — it was his belief that most people tend to overeat, as he had written in a series of articles on health in 1913. “All will agree that out of every 100,000 persons 99,999 eat merely to please their palate, even if they fall ill in consequence. Some take a laxative every day in order to be able to eat well, or some powder to aid digestion... Some die of thoughtless overeating.” Human beings, in his opinion, compared unfavourably to cows in this regard: “Cattle do not eat for the satisfaction of the palate, nor do they eat like gluttons. They eat when they are hungry — and just enough to satisfy that hunger. They do not cook their food. They take their portion from that which Nature proffers to them. Then, is man born to pander to his palate” (Indian Opinion, 1913). He also pointed out that “we have turned our stomach into a commode and that we carry this commode with us wherever we go”. Another time he emphasised, “Instead of using the body as a temple of God we use it as a vehicle for indulgences, and are not ashamed to run to medical men for help in our effort to increase them and abuse the earthly tabernacle.” Therefore, it’s not surprising that I wasn’t asked for any preferences, but simply served chapattis, a boiled vegetable hotchpotch featuring home-grown beetroot and a modest salad. The only seasoning I tasted was salt. Basic but edible — and it reflected the Gandhian ideals of eating food as if it were a medicine “to keep the body going”. Prayers were offered before the meal and there was an embargo on conversation while eating. “Silence is obligatory at meals. It is uncivil and a form of violence to criticize while eating any badly cooked item of the food. Such criticism should be conveyed to the manager in writing after the meal,” Gandhi wrote in 1940 (Ashram Notes). As I look at notes by visitors to the ashram back in the day, I find that the menu has not changed significantly. In those days, Gandhian cookery was considered truly spaced out, as gastronomic experiences go: A “steaming hell-brew served up in a great bucket” is one Englishman’s description of the “ashramatic” menu, as mentioned in Ramachandra Guha’s biography of the British-born anthropologist Verrier Elwin, Savaging the Civilized. Elwin spent a month with Gandhi in 1931 and even jotted down a poem titled Thoughts Of A Gourmet On Being Confronted With An Ashram Meal: “O food inedible, we eat thee/O drink incredible, we greet thee./ Meal indigestible, we bless thee./ O naughty swear-word, we suppress thee.” A more articulate and fairly rationalistic critique was framed in 1915 by Gandhi’s own son Harilal, then 26 years old, who’d later go on to take a very different path from his father’s. His letter suggests that his father was not, for example, always into salty food: “I cannot believe that a salt-free diet or abstinence from ghee or milk indicates strength of character and morality. If one decides to refrain from consuming such foods as a result of thoughtful consideration, the abstinence could be beneficial. It is seen that such abstinence and asceticism is possible only after one has attained a certain state. By insisting on salt-free diet and on specific abstinences, at the Phoenix institution [Gandhiji’s ashram in South Africa], you are trying to cultivate self-denial.” Harilal, who used strong words such as hypocrisy when it came to altering people’s food habits unless combined with the right mental qualities, was critical of fasting, too: “It is well-recognised that among the Hindu families thousands of women and men observe rigorous vrata round the year. They observe fasts, but barring a few exceptions, they possess no sterling virtues; and good character is found also among those who do not observe any vrata.” Even for modern holidaymakers, this ashram might not compare favourably with a beach resort in Bali, but I actually considered staying on for some days, thinking that I’d shed excess weight. Thanks to the light and early meal, I slept well, except for the mosquitoes, which I didn’t dare swat so as not to break ahimsa regulations. Wake-up time was 4 am for prayers, just like when Gandhi was still around. Afterwards, I was told to spend my morning weeding a patch of grass behind the latrines. After a 6 am breakfast, there was spinning for two hours — a calming exercise akin to meditation. Today, in the age of health supplements in newspapers and magazine stories on wellness and food fads, it’s easy to see that Gandhi was a pioneer in the field, devoting much space in his journals to health advice. His biggest bestseller during his lifetime wasn’t The Story of My Experiments with Truth, but the booklet A Guide to Health — which was full of cooking instructions. It was reprinted several times and translated into many languages in India and abroad. Gandhian nutritional principles, were I to attempt to sum them up, are based on the notion that everybody must know how to cook their own food or, even better, not cook at all — which in turn calls for simplicity and the avoidance of complex culinary methodology. This thinking is increasingly catching on nowadays and is perhaps best reflected in the mix-your-own-salad bars that dot many cities in traditionally non-veg territories such as the US and Scandinavia. Secondly, in eating wholesome food, one would eliminate the need for going to doctors and pill-popping. As Gandhi put it: “I believe that man has little need to drug himself. 999 cases out of a thousand can be brought round by means of a well-regulated diet.” Gandhi’s own awakening in this regard started during his student days in London when he, out of financial necessity, learnt how to prepare his own food. This is also when he found his first English friends among the members of the London Vegetarian Society. Vegetarianism was a philosophical idea for this movement — in the late 1800s, when isms, whether political, spiritual or otherwise, were the in-thing — and the restaurants the movement ran (such as Central Vegetarian Restaurant in 16 St Bride Street, which, unfortunately, was bombed off the planet by Hitler during World War II) were more of public clubs where the young Gandhi discovered a platform for his ideological development. “I saw that the writers on vegetarianism had examined the question very minutely, attacking it in its religious, scientific, practical and medical aspects” (Experiments in Dietetics, 1926). Once he found his feet among like-minded folks, the vegetarian movement proved as edifying an experience as studying law. “Vegetarianism was then a new cult in England, and likewise for me, because, as we have seen, I had gone there a convinced meat-eater, and was intellectually converted to vegetarianism later. Full of the neophyte’s zeal for vegetarianism, I decided to start a vegetarian club in my locality, Bayswater. I invited Sir Edwin Arnold, who lived there, to be Vice-President,” he wrote in one of his autobiographies. Sir Edwin was, apart from a confirmed Indophile, also editor of The Daily Telegraph and so a useful contact to make. Soon, Gandhi was reporting about Indian food culture in journals such as The Vegetarian. “Diet cure or hygiene is a comparatively recent discovery in England. In India we have been practising this from time out of mind,” he wrote cockily as only a 21-year-old can do. However, this juvenile journalistic experience laid the foundation for his interest in print media as a tool for spreading ideas. Having encountered all kinds of health theories in London, he would, for the rest of his life, go on bravely experimenting with food — no-breakfast, fasting, vital foods, raw foods, no-starch (essentially a precursor of what was to evolve into the even more specialised gluten-free diet), milkless (a precursor of lactose-free), sugarless and pickle-free eating, and of course fruitarianism — as much as he experimented with truth. Now and then, projects had to be abandoned as they caused depression, headaches, dysentery and weakness to a degree that he could barely walk. Chewing on hard uncooked grains broke his teeth. Harilal certainly doubted many of these fads and, for example, debated his father’s fruitarianism in the aforementioned letter: “If my own experience or experiment of being a fruitarian for only twenty days has any validity, I speak with experience — I have also observed this characteristic among those who were fruitarians for six months — that people eat fruits and nuts far in excess to even those who overeat roti and dal. Therefore, indigestion is bound to happen. Under such circumstances I see no benefits in adopting a fruit diet.” Nevertheless, despite his own occasional doubts and fierce criticism from kin and acolytes, Gandhi developed a plan, which, according to him, would be the best for mankind. It was the most functional eating strategy imaginable — and it is, of course, vegetarian fare rich in fruit. “A comparison with other animals reveals that our body structure most closely resembles that of fruit eating animals, that is, the apes. The diet of the apes is fresh and dry fruit. Their teeth and stomach are similar to ours” (Indian Opinion, 1913). The ideal way was to cut down the number of ingredients. A sample menu from 1935 for village workers contained the following: Wheat flour baked into chapattis, tomatoes, red gourd, soya beans, coconuts, linseed oil, milk, tamarind and salt, and then some jaggery and wood apple combined into a “delicious chutney”. Already in 1929, Gandhi had described a scientific ahimsa cuisine that would “reduce the dietetic himsa that one commits”. He pointed out: “Dieticians are of the opinion that the inclusion of a small quantity of raw vegetables like cucumber, vegetable marrow, pumpkin, gourd, etc., in one’s menu is more beneficial to health than the eating of large quantities of the same cooked. But the digestions of most people are very often so impaired through a surfeit of cooked fare that one should not be surprised if at first they fail to do justice to raw greens, though I can say from personal experience that no harmful effect need follow if a tola or two of raw greens are taken with each meal provided one masticates them thoroughly.” Gandhi’s own food intake, for much of his adult life, consisted of fixed quantities of grains such as sprouted wheat, grated veggies, 40 grams of fat and a similar measure of sugar or honey, and fruits. In 1934, he gave instructions to supporters who wished to host him on his tours: “Fried things and sweets must be strictly eschewed. Ghee ought to be most sparingly used. More than one green vegetable simply boiled would be regarded as unnecessary. Expensive fruit should be always avoided.” This may sound unappetising to a gourmet, but culinary experts will agree that a certain frugality might actually heighten basic flavours. In fact, what Gandhi advocated would nowadays be considered a preferable fare and, for ethical reasons, food ought to be grown in the vicinity (if not in one’s garden) entailing a minimal carbon footprint for transportation. The emphasis on fresh local ingredients is embraced by chefs who see the ridiculous in, say, flying salmon from Norway to Goa, where there’s so much fish locally available. But, above all, the way he explored the relationship between eating and health in an age when the concept of ‘health food’ was unknown to most, gave me plenty of — what else — food for thought. Or, to quote Gandhi after one of his communal dietary adventures, “The experiment is not an easy thing nor does it yield magical results. It requires patience, perseverance and caution. Each one has to find his or her own balance of the different ingredients. Almost every one of us has experienced a clearer brain power and refreshing calmness of spirit.” In conclusion, one might not be faulted for thinking that there’s still a lot to be learnt from Gandhi’s willingness to experiment with what might be the best for the body and soul. Courtesy: The article has been adapted from The Hindu Business Line, dt. 21.2.2020 Zac O' Yeah writes detective novels and travelogues, but is also the author of the Gandhi biography Mahatma! which was shortlisted for the August Prize as the best Swedish non-fiction book of 2008. |