Some men changed their times...

One man changed the World for all times!

Comprehensive Website on the life and works of

Mahatma Gandhi

+91-23872061

+91-9022483828

info@mkgandhi.org

+91-23872061

+91-9022483828

info@mkgandhi.org

Salt and the National Imaginary: The Photojournalism of the Dandi Satyagraha |

- By Elisa deCourcy* & Miles Taylor#AbstractThis article looks at how Gandhi used the Dandi Salt Satyagraha as a site for imagining anti-colonial nationalism. We focus on the visual dimensions of the Salt March and the divergent ways in which it was reported in the illustrated press in 1930. Developing Sumathi Ramaswamy’s idea of the ‘ambulatory aesthetic’ (2020), we highlight how Gandhi created a personified protest. Moreover, he chose salt as a talismanic object, ubiquitous both temporally, back through India’s colonial and pre-colonial past, and laterally, bridging religious identities but also illuminating class distinctions. We also describe how Gandhi’s curated defiance was deliberately mutated and muted by the British, initially by way of censorship, but mostly through using biased visual newspaper and magazine reportage of their own in order to marginalise Gandhi and the salt marchers. IntroductionThis article looks at how Gandhi used the Dandi Salt Satyagraha as a performative site for imagining anti-colonial nationalism. We argue that it was an image that was ultimately simplified, and thus re-colonised, in the British colonial press by focusing on the visual dimensions of the Salt March and its corollary, the reporting of the protest in the illustrated press. We will assess salt from the point of view of an object-oriented history. Nico Slate and others have examined how Gandhi’s embodied use of salt—that is to say, Gandhi’s own dietary choices—intersected with the development of his broader political philosophy.1 We use embodiment from a different point of view: at a surface level, investigating the body as a canvas for the expression and extension of ideas. Salt became inextricably connected to the outward image of Gandhi in 1930. Its simplicity and relative ubiquity rendered it poignant and malleable, allowing its discussion to stretch back through India’s colonial and pre-colonial past as well as laterally, bridging religious identities but illuminating class distinctions. The ‘theatre’ of the protest became a stage for the articulation of ideas about nationhood and the colonial predicament that intersected on the material of salt. Following from this, we want to evaluate how this ‘rich’ image of curated defiance was translated and represented by the imperial power, specifically in photographic form in the British illustrated press. In his writings and actions, Gandhi fashioned salt as an economic symbol for imagining India’s separateness from the monopoly of British colonialism and as a secular tool through which to imagine a new modern nation-state. Benedict Anderson famously argued in 1983 that nations were ‘imagined communities’. For Anderson, this socio-cultural imagination was facilitated by print capitalism and increasing literacy in the nineteenth century that gave nascent citizens the tools and material through which to imagine themselves as part of a political organising structure beyond the physical parameters of their lived experience.2 While Anderson’s scholarship deals primarily with the European context of nation-statehood, his work is pertinent here for drawing attention to the explicitly constructed nature of a democratic national consciousness—a consciousness not imposed from a governing elite but one of collective participation and cultivation. More recently, the work of Anthony Smith and Zdzislaw Mach has explained how this idea of an imagined community directly links to discussions of national symbols.3 Smith’s work examines what he terms the ‘myth-symbol complex’ whereby selected practices and traits of an ethnic (pre-national) community are drawn upon in the creation of a national image.4 While acknowledging the state as a political organisation, Mach asserts the nation is first and foremost a cultural entity, an important dimension or measure of which is the collective adoption of symbols and rituals.5 Symbols used within modern anti-colonial nationalist movements take on further significance than those articulated within Europe. Salt, for example, was galvanised as a nation-building tool from under what Sumathi Ramaswamy has called the ‘imperial optic’, that is the pictorial practices, image-making technologies and vision-oriented subjectivities of the imperial power. More recently, Ramaswamy has showcased Gandhi’s ‘ambulatory aesthetic’: how he, his supporters and publicists then and since deployed his body as a canvas for the expression of resistance to British rule.6 We show how salt’s construction and creation as a symbol provided potent alternatives for visualising the colonial space and a separateness of the colonised peoples. Its challenge was not singularly ‘imagining’ in an Anderson sense, but re-imagining and re-claiming. The first part of this paper draws from Gandhi’s own newspapers, Young India and Navjivan, as well as transcriptions of his speeches and the dozen or so press interviews he gave around and during the Salt March, themselves interventions in the print capitalism of empire. It will briefly sketch how salt was moulded into a dynamic symbol within spoken and written discourse, and also further assess how these sentiments resonated in the design and visuality of the March. We will then examine the translation of Gandhi’s message through salt, as it was ‘interpreted’ in illustrated British journalism. What parts of its richness were lost? How was salt and the image of Gandhi squeezed once again into the imperial optic despite the sophistication of its original articulation? Salt:'A body in part to the elusive word Independence'Writing to Lord Irwin before the Salt March on March 3, 1930, Gandhi articulated how the Viceroy’s lack of commitment to facilitating the transition of India from colony to dominion status represented an ‘unpalatable truth’.7 He wrote that the colonial predicament had ‘impoverished the dumb millions by a system of progressive exploitation and by a ruinously expensive military and civil administration’; it had ‘reduced [the subcontinent’s population] politically to serfdom’, and ‘sapped the foundations of [its] culture’.8 This was language of force, direct, representing an embodied sense of simultaneous destabilisation and oppressive smothering. In this letter, penned from Sabarmati, and delivered in person to the Viceroy by Reginald Reynolds, an English Quaker and resident of the ashram, salt is configured by page eight as the epitome of these broader colonial grievances. Gandhi had edited an issue of Young India the previous week—published on February 27—incorporating a long-form discussion of the issue of salt. In it, J.C. Coomarappa tabulated the percentage of government revenue extracted from salt regulations describing its disproportionate effect on the poor.9 Gandhi outlined in his own essay, within the same issue, the three frontiers of salt’s control: the licensing of its large-scale manufacture, removal or transportation; the ban on the excavation, collection and removal of naturally occurring salt; and the outlawing of the possession and sale of contraband salt.10 Gandhi’s articulation of salt in his essay concentrated on its status as a life force, beginning at the level of the individual body as a nutrient or nourishment, moving to the land as a fertiliser, rising to a central commodity in a domestic industry, and finally becoming definitive of the body politic: a locus for imagining an egalitarian common good. It is unsurprising that this late February issue of Young India also included a commentary on khadi and the re-emerging weaving industry for indigenously-produced cloth. Khadi had been the focus of campaigns of the previous decade and, as Emma Tarlo and Lisa Trivedi have discussed, it was described in terms of a movement to ‘clothe Gandhi’s nation’.11 This is the same cloth, coarse and plain, antithetical to the ornamentation of empire, which is seen on Gandhi and the sea of satyagrahis who converged on Dandi in April 1930. The khadi campaign of the 1920s was also a Swadeshi Movement which focussed on re-introducing women into the labour market as crucial and important agents, displacing imported cotton with local artisan-based products, and thus cultivating national producers beyond the large-scale capitalist machinery of empire. Speaking at a prayer meeting at Sabarmati the day prior to the beginning of the Salt March, Gandhi asserted that the ‘reins of the moment remain in the hands of those of my associates who believe in non-violence as an article of faith’.12 Here we see salt described as something within grasp; containable and reachable by the hand; the idea of touch and agency returning to the marchers. Importantly, the ‘faith’ Gandhi spoke of was a ‘faith’ in an emerging nation and non-violent protest as its means to creation, stating ‘Hindus, Muslims, Christians, Jews and others…the salt tax applies equally to us all’.13 He would claim in Young India on March 12, 1930, that he had ‘never had any difficulty reading the message of non-violence in the Quran…[and that] Musalmans are actually enlisted in the march, as they have no difficulty subscribing to the creed of non-violence for the purpose of Swaraj’.14 Indeed, as Yogesh Chadha outlined, the 78 followers who left Sabarmati on March 12 were chosen to symbolise the nascent nation’s religious diversity and, as Thomas Weber identified, the up to 50,000 people who distilled salt at Dandi on April 5 included representatives from across the subcontinent’s spiritual traditions.15 Gandhi claimed the philosophy of non-violent protest was not founded in the teachings of a specific faith nor was salt aligned with the iconography of a particular religious tradition. Rather he used the discourse of religious observance to position the mundane but staple commodity of salt as a symbol that could unite across spiritual belief systems. The salt campaign—described by Gandhi in an interview on arrival at Dandi as ‘sacred work’16—did not represent an unprecedented or an enduring sense of interfaith dialogue. Nevertheless, Gandhi’s use of salt as a symbol for this movement did attempt to look beyond religious identity and find a sense of commonality and inspire a collective devotion to the anti-colonial cause. Speaking at Aslali, Gujarat, four days into the Salt March, Gandhi conflated his lateral pilgrimage to the sea with the metaphor for the protest as climbing, using salt as an analogy for ascending the first rung to Independence. He spoke to his assembled audience about the salt restrictions as representing a crippling poverty and the body of the indentured, or licensed, salt worker as without the strength to repel the tax that left him destitute. For Gandhi, collective non-violent protest was to climb out from beneath the economic oppression of empire, enacted and felt on the body of the worker but the responsibility of all who used salt to shrug it off. Gandhi’s evocation of salt as the pivot for the protest, and as central to dismantling the economic framework of empire, was based in its entangled history with imperial expansion from the early modern period covered elsewhere in this volume. He labelled the British regulation of salt a ‘nefarious monopoly’ that had the ‘necessary consequence of [indigenous] destruction’.17 This was a sentiment gestured to not only by the impoverished nature of the salt industry in India, but also salt works’ longer legacy of supporting raw commodity trade and the tentacles of imperial control. Gandhi wrote in the nationalist newspaper Navjivan that the salt campaign was also an opportunity for personal atonement.18 Salt’s simplicity and purifying properties analogised the necessary self-restraint of Swaraj as at odds with more corrupting indulgences. Salt was chosen to reify class divides and discrepancies in wealth. Gandhi would outline how the supply of salt represented two days’ average annual salary, but that this was felt disproportionally greater among the peasant classes.19 The march, its design and the alms Gandhi and his satyagrahis were permitted to accept from villagers also put in check unnecessary food rations, lavish accommodation and banned alcohol and tobacco as vices that were at disjunction to the philosophy of non-violent protest.20 On the eve of departure, Gandhi explained in an interview with Haridas Muzumdar that the march through Gujarat would be different from his 1913 march across the Transvaal in South Africa: this time, local people would be supportive and ‘hospitable’, sharing their food. At Navagam a few days later, Gandhi told the press representatives following the March that they were also expected to be frugal.21 In this way, salt was a social leveller, emphasising the poverty of those struggling to afford this staple preservative. The March was described by Gandhi not just as a pilgrimage destined for an end-point on the Dandi coast, but the opportunity to cultivate a lifestyle pared back from the unnecessary consumption that fuelled imperial capitalism and corroded a socialist consciousness. In mobilising a national imaginary around the symbol of salt, Gandhi faced a major obstacle: the bias and censorship of the media in colonial India. An experienced journalist himself, Gandhi recognised the opposition he faced from newspapers loyal to the British, both in India and back in London. One reason he despatched Reynolds with his letter to the Viceroy in early March 1930 was his distrust of the principal English newspapers, notably The Times (of London).22 For its part, The Times of India was hostile throughout the March, its denigration of Gandhi summed up in a huge cartoon of March 28 depicting civil disobedience as ‘A Frankenstein of the east’.23 Gandhi had the means to circumvent all this. As Isabel Hofmeyr has persuasively argued, Gandhi believed newspapers were important for circulating and recycling information, as much as for reporting ‘news’ or opinion.24 In this way, Gandhi relied on his own newspapers to republish his speeches during the March, together with sympathetic newspapers such as the Bombay Chronicle, Hindustan Times (Delhi) and Amrita Bazar Patrika (Calcutta, now Kolkata), as well as magazines such as the Indian Social Reformer (Bombay, now Mumbai) and the Modern Review (Calcutta), thus counteracting the negative coverage in the mainstream Anglo-Indian press.25 In addition, vernacular editions of his articles and speeches from Young India and Navjivan during the March were reprinted in cheap editions in Ahmedabad (Gujarati), Calcutta (Bengali) and Bombay (Marathi).26 However, it soon became clear that his words were not being relayed correctly in some of the English-language press. Gandhi himself commented on misreporting, and so did the correspondent from the Bombay Chronicle, who pointed a finger of suspicion at the local telegraph officials.27 Moreover, newsreel footage of the March was suppressed. Three separate films were made of the satyagrahis leaving Ahmedabad on March 12 and of the early stages of the March—all were banned by the Bombay government.28 By the end of April 1930, media bias, inaccuracy and local censorship were compounded by the reintroduction on April 27 of the Press Ordinance of 1910, which brought in severe restrictions on newspaper reporting of activities, speeches and opinions purported to be seditious. All Indian newspapers were required to provide hefty financial security against prosecution and be mindful of what speeches they reprinted.29 Caution became the watchword in the nationalist press. For example, whereas the Bombay Chronicle had been happy in mid March to print a Congress advertisement calling for ‘70,000 lakhs of soldiers of freedom’ to enter the ‘field of battle’,30 by the time of Gandhi’s arrest at the beginning of May, its reporting was much more circumspect. Later, in July, the ordinance was extended to cover the re-publication or cyclostyling of newspapers. Undeterred, Gandhi exhorted his followers to close their printing presses and resort to handwritten news-sheets.31 In addition, the British authorities stamped down hard on the visual iconography of satyagraha. The distinctive white hats of civil disobedience as well as the national flag unfolded as Purna Swaraj (Independence) at the Indian National Congress meeting in Lahore at the end of 1929 were also proscribed. Although almost impossible to police in practice, these restrictions toned down how Gandhi’s Salt March was visually reported in Indian newspapers. Until the mass breaches of the salt laws, particularly in Bombay during May and June, very few photographs of the Salt Satyagraha actually appeared in Indian newspapers. Whilst photographs of Gandhi’s staged scooping up of salt from the sand at Dandi on April 6 were included in Indian newspapers, the photojournalism of the previous three weeks of the March was not. Indian news photographers and illustrators accompanied the March: for example, Kanu Desai, who was a protégé of the artist Nandalal Bose, was there, as was the staff photographer of the Amrita Bazar Patrika. But for whatever reason, their work only saw the light of day in a special issue of the Modern Review published later in May.32 The images captured by the photographer and the special drawings made by Desai—of crowds leaving Ahmedabad, or the mass gatherings en route at Nadiad and Keda, the satyagraha camps, or the beginnings of the Salt Satyagraha in Bengal—did not make it into the large circulation newspapers in India, thereby limiting the dissemination of Gandhi’s subversive rhetoric during March and April, making it easier for the authorities to downplay the ‘national’ or popular reach of the campaign. Imag(in)ing the Salt March in the imperial pressDespite the censorship, Gandhi did succeed in endowing salt with an economic, social and nationalist message when it most mattered, at Dandi beach, on April 6, 1930, when, dressed in khadi and simple sandals, he bent down and broke the salt laws by extracting a handful of salty silt from the shoreline. How was this moment, and the march that preceded it, reported in the British illustrated press, the media which filtered how much of the events in India the rest of the world viewed? The image content of the press expanded exponentially from the middle of the nineteenth century, firstly with developments in the reproductive capacity of steel engravings and then, in the twentieth century, with innovations in two-tone printing that allowed for the direct reproduction of photographic content. British newspapers disseminating illustrated content, such as the Illustrated London News (established 1842), the Graphic (1869–1932) and the Daily Mirror (established 1903), had huge readerships, not only in the metropole but in the colonies, where they were exported with speed to settler communities.33 The March, and the contraband distillation of salt at other sites of protest across the subcontinent in 1930, were also covered in the American press and through visual channels beyond the purview of imperial power.34 Resonating with Ramaswamy’s notion of the ‘imperial optic’, the following examples of British pictorial journalism made sense of the salt campaign by repositioning the protest in line with colonial tropes that had persistent dissemination in other visual ephemera of empire. The Graphic won the race to report the Salt March to British readers, having exclusive use of the Swiss-German agency photographer, Walter Bosshard.35 Bosshard’s pictures featured first in the issue of March 15, just three days after Gandhi and the 78 satyagrahis set out from Ahmedabad, and showed Gandhi and his principal colleagues, with a further series in the April 5 issue, which depicted the marchers en route, and their supporters, including women.36 These images convey the chaotic excitement and the popular mobilisation that characterised the early stages of the March. They remain a unique and under-used resource for researching civil disobedience in India. However, the Graphic proved determined to put its own spin on the photographs. In its editorial, ‘Gandhi Goes Walking’, it presented Gandhi as a ‘holy man’, ‘less interested in temporal realities’, confused about civil disobedience and unaware of its potent power. The captions to the photographs continued the commentary. Singing satyagrahis were described thus: ‘They are forming a chain of hands as if they are singing “Auld Lang Syne,” but the post-prandial song has no echo in their mouths’. Women visitors to the Sabarmati ashram were labelled as ‘hero-worshippers of Ind: feminine fanatics’.37

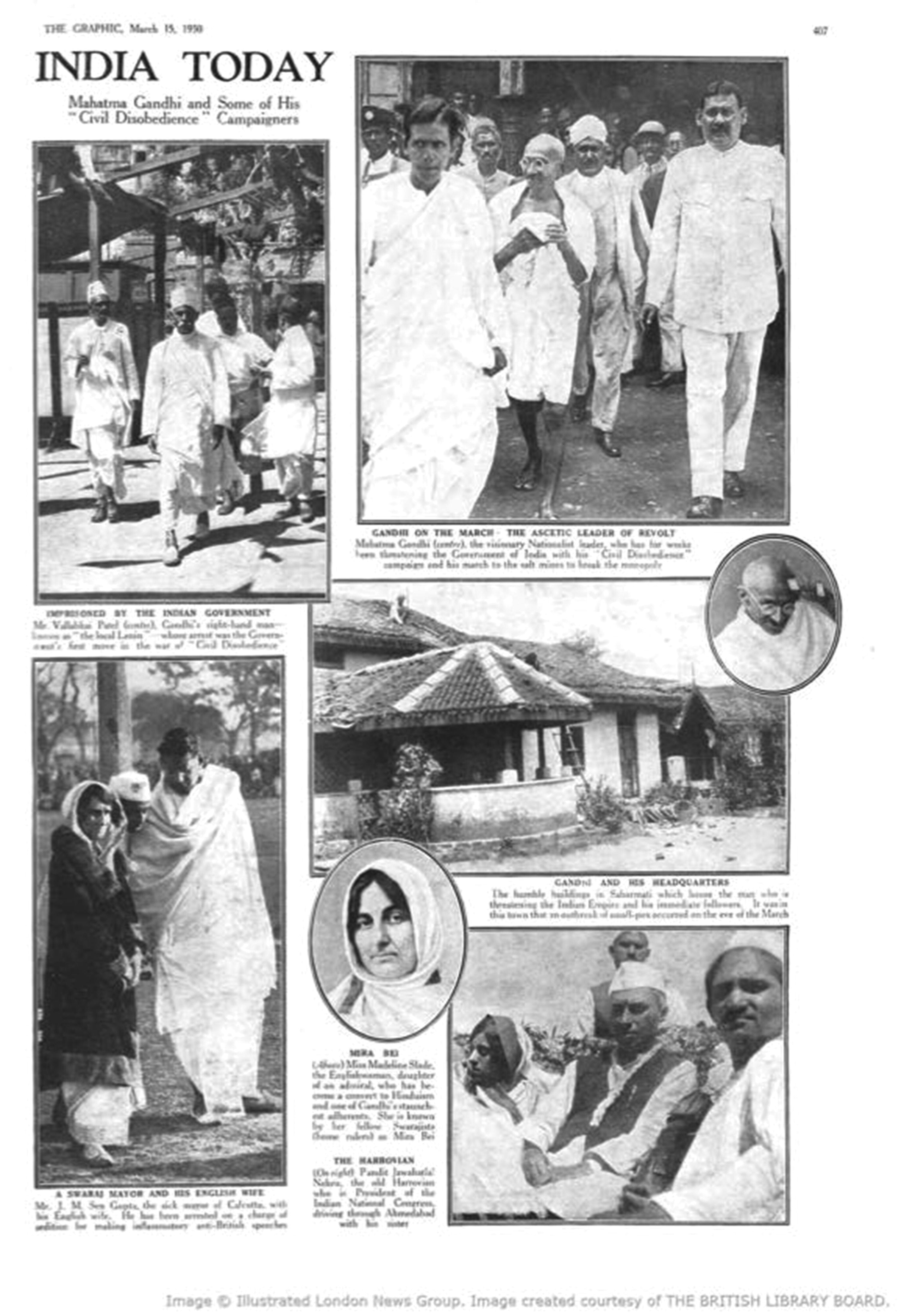

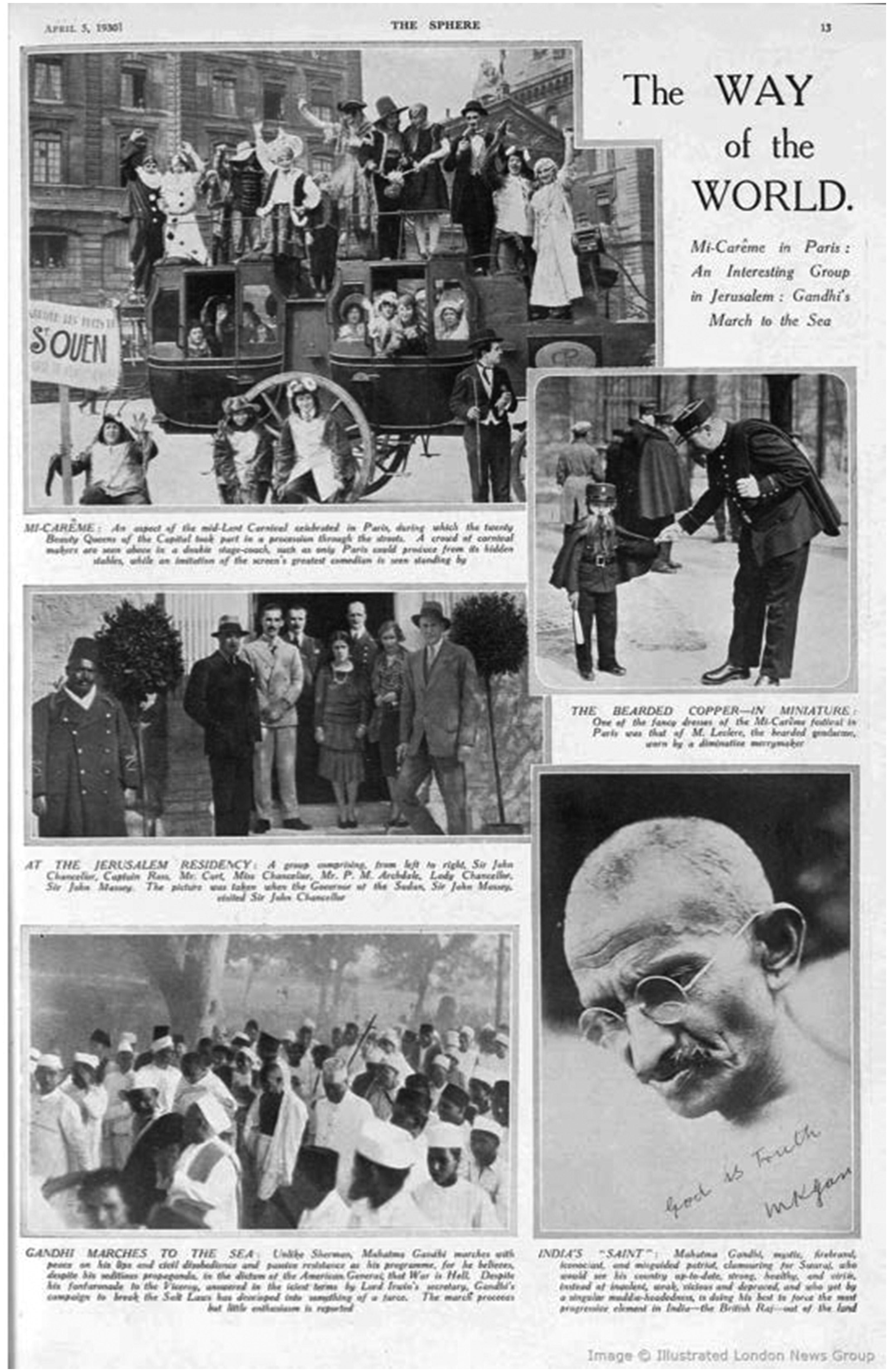

Gandhi depicted as the ‘ascetic leader of revolt’ Graphic, 15 March 1930. / Image credit: THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD Other British newspapers followed suit. On April 5, 1930, the day before Gandhi broke the salt laws at Dandi, The Sphere included a portrait of him and one of his marches in a full-page photo essay entitled ‘The Way of the World’.38 In the vignetted head shot, Gandhi is pictured pensively downcast, without ornamentation or accessory besides his simple-rimmed glasses. The paper’s caption provides no context on the economic history of salt nor the hiatus in Gandhi’s talks with Lord Irwin that had preceded the campaign. Rather it claims the Indian subcontinent is ‘up-to-date, strong, healthy and virile’ as a consequence of imperial rule—wording that describes government in terms of gendered vocabularies. Conversely, Gandhi as the subject of the portrait, the face of the anti-colonial nationalist campaign, is described as ‘indolent, weak, vicious and depraved’ and ‘singularly muddle-headed’.39 The Sphere sidelined the economic message of imperial exploitation the protest was designed to aesthetically illuminate. Instead, it evoked a discourse of competing masculinities, which Mrinalini Sinha and others have identified as foundational to how the Raj justified its rule from the mid nineteenth century. As Sinha argues, physical fitness was discussed as synonymous with political fitness by the imperial power, irrespective of actual physiognomy. Hierarchies of masculine fitness were constructed by the British to articulate different ethnic and regional groups’ relationships to property, power and governing legitimacy.40 Gandhi’s vignetted bust shot abstracts his body from his face, but it also presents him with a sense of condensing sentimentality. His message of non-violent protest was eschewed as simultaneously effeminate—an identity read back into the representation of his photographically absent ‘body’—and as a seditious act. The March is described as ‘somewhat of a farce’, and, by implication of its publishing context, compared to the theatrics of the Lent carnival of the Mi-Carême in Paris. The marchers are further reported as ‘lacking enthusiasm’, and the soft tones of the bottom-left image make it almost impossible to distinguish Gandhi at the centre of the group, as a leader or pivot, an identification not made clear by the caption. On April 7, in its first photograph of the March, the London Times placed centre-stage the horse and carriage supplied for Gandhi, in case he tired (it was never used).41 In its first montage, splashed across its front page, the Daily Mirror showed the vast crowds leaving Ahmedabad, but noted pointedly that ‘since, Gandhi’s followers have become considerably fewer’.42 A week later, writing in the Sphere, ‘Ajax’ reinforced the point in a photo-essay depicting salt-workers in the Rann of Kutch: ‘[t]hese men would resent any attempt by the Soul-Force Swarajists to interfere with their livelihood’.43

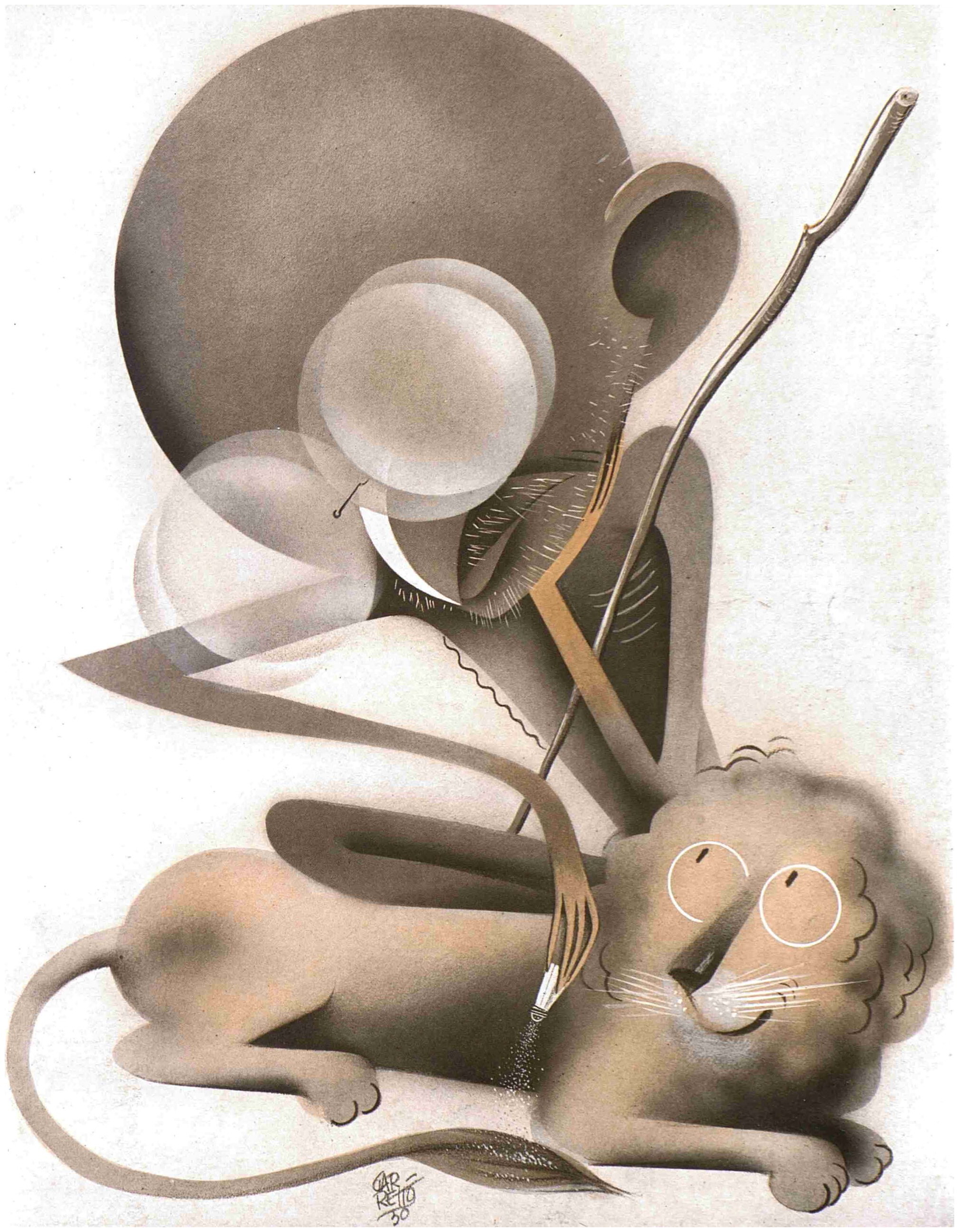

Gandhi depicted as the ‘misguided patriot’ Sphere, 5 April 1930. / Image credit: Illustrated London News Group The Illustrated London News (ILN), a paper whose inception parallels the development of photography, would move to discredit and defuse the political message of the March by focusing on its pre-industrial orientation. It published photo essays on April 26 and May 3 about Gandhi’s arrival at Dandi and the progress of distilling salt at other sites along the Indian coastline. Unlike The Sphere, the ILN identified Gandhi in the busy group of khadi-clad satyagrahis with a small arrow, but the caption again emphasises his relationship to property, highlighting his ‘bare-bodied’ and ‘bare-headed’ appearance.44 The ILN mentioned the evasion of the salt tax but suggested it was only those marching with Gandhi from Sabarmati who were responsible for participating in the distillation of salt at Dandi. The second instalment a week later emphasised the unruly nature of non-violent protestors in Madras (now Chennai), whom the paper described as a ‘mob’, and then focused on Calcutta, where it outlined the supposedly futile efforts to produce salt. The paper captioned a photograph of a party of men pouring jugs of sea water into a straw-topped distillation trough, with the ‘advice’ that it took 34 men a full day to produce two tablespoons of salt.45 Other papers such as the Daily Mirror had claimed earlier on April 7 that the salt being produced by the satyagrahis was of such inferior quality that it was impossible to classify it as an infringement of law.46 Scenes of unindustrialised labour characterised British representations of the South Asia economic landscape for the duration of their colonial rule. For example, in the early twentieth century, Anandi Ramamurthy’s scholarship examined how commodity advertisement, particularly for tea, was visually predicated on constructing ‘idyllic’ scenes of indigenous industry where imperial plantation owners exercised vertical control over labour forces.47 Indentured planters and pickers were drawn in orderly lines, as productive workers in broader systems of capitalist production and consumption that extended beyond the frame of commodity advertisement. The ILN’s photo essay evokes that notion of vertical control framing a reading of its images as resulting from the lack of imperial command, and the outcome, it leads its readers to believe, is unruliness and regressive unproductivity. This representation of the marchers as conglomerations of disorganised bodies undermined its organisation and the scope of the protest, and eschewed salt’s symbolic representation of excessive imperial taxation. The Sphere would reiterate this binary of Western modernity versus Indian backwardness in a pair of photo-essays at the end of May, depicting a ‘real’ India ‘[w]here the inhabitants know nothing and care less for the Gandhi campaign’.48 Gandhi’s arrest in early May provided a natural end-point to the disturbances as far as the British press was concerned. The Daily Mirror chose to juxtapose a head-and-shoulders photograph of Gandhi with a group portrait of the British royal family celebrating the twentieth anniversary of George V’s accession. The ILN emphasised the role of the riots in the days leading up to his detention. Even the Left-wing Daily Herald headlined with ‘Indians Mourn Their Leader’s Arrest’.49 This glossing of the story was in spite of interviews given by Gandhi during May—for example, with Ashmead Bartlett in the Daily Telegraph and with George Slocombe in the Daily Herald—in which he spelt out his philosophy of non-violence and the continuing course of the campaign.50 As in earlier episodes of colonial resistance, such as the South African war of 1899–1901, newspapers in Britain’s white colonies tended to follow and ape the metropolitan press in their coverage of Gandhi’s Salt March. Without access to up-to-date images, newspapers in Australia and New Zealand, for example, resorted to photographs of Gandhi found in old library cuttings—with a full head of hair or in European dress—to accompany their initial notices of the March.51 As was the tradition with much circulated international news, many colonial Australian papers relied on reprinting word-for-word reports from the Times of London, or borrowing (without attribution) commentary from British newspapers.52 The same bias was in evidence. Satyagrahis were referred to as Gandhi’s ‘group of friends’. ‘Passive’ resistance was reported with scepticism.53 Only those newspapers that looked beyond the colonial metropole for news from India suggested a different angle. For example, on March 15, the Manawatu Daily Times in New Zealand reprinted Upton Close’s positive assessment of Gandhi from the New York Times: a man who ‘can mould his age’.54 Indeed, within a few weeks, the racist and colonialist tropes used by the British press to denigrate Gandhi and deny the potency of his protest were being challenged by the pictorial press outside the British world. Starting with Time magazine’s depiction of ‘Saint Gandhi’ on its March 31 cover, the visualised Gandhi became ‘the most talked about man in the world’, despite the best efforts of the authorities in India. Time later likened Gandhi’s Salt March to the American colonists who threw tea into Boston Harbor in 1773. By the time of the Dharasana raid in May, during which American journalists telegraphed home live reports of police beatings of the satyagrahis, Gandhi was made over as a hero of the struggle against empire: ‘un uomo contra un impero’ as La Stampa (Turin, Italy) pronounced him across the front page of its April 8 edition.55 Even the British press conceded defeat. Towards the end of May, the Graphic commissioned the Italian artist Paulo Garretto to draw a caricature of Gandhi. ‘Gandhi the Tail-Salter’, showing Gandhi taming the British lion, spoke volumes about this new iconic status, and the image was quickly reproduced around the world.56

Gandhi as caricatured as the ‘Tail-Salter’, The Graphic, 24 May 1930. Print journalism, transcribed speeches and the illustrated press on the salt campaign thus highlight what Ramaswamy describes as the ‘nexus between power and visuality’. Gandhi’s own articulation of salt as a symbol of anti-colonial protest and national imagining had a localised dissemination in the emerging nationalism of the press in India. However, his message was one that was problematically translated in the imperial space and broader communication conduits of empire. We see how the sophisticated visually-oriented discourse of the March was marginalised in the British pictorial press. Images of what we call ‘curated defiance’ were reinscribed with imperial visual discourses and knowledge to undermine the symbolic construction of salt and the legitimacy of the movement. Ultimately, Gandhi’s message did reach a wider audience, albeit outside India and the colonial world, and then only via caricature and not the camera. In colonial India, photojournalism obscured more than it revealed. AcknowledgementsThe authors would like to thank their anonymous reviewers and readers for their recommendations which helped improve the piece as well as the participants of the workshop ‘Salt and public health in India, past and present’. Elisa deCourcy would like to acknowledge the late Michael J.D. Roberts who originally supervised an earlier iteration of this work over a decade ago. Notes

Courtesy: deCourcy, E., & Taylor, M. (2023). Salt and the National Imaginary: The Photojournalism of the Dandi Satyagraha. * Elisa deCourcy, a Centre for Art History and Art Theory, Research School of Humanities and the Arts, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia. Email: Elisa.DeCourcy@anu.edu.au # Miles Taylor, a Centre for British Studies, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Berlin, Germany. Email: miles.taylor@hu-berlin.de |