Sunderlal Bahuguna: A Perpetual Archetype of Gandhian Ethics |

- By Professor (Dr.) Rajkumar Modak*Abstract

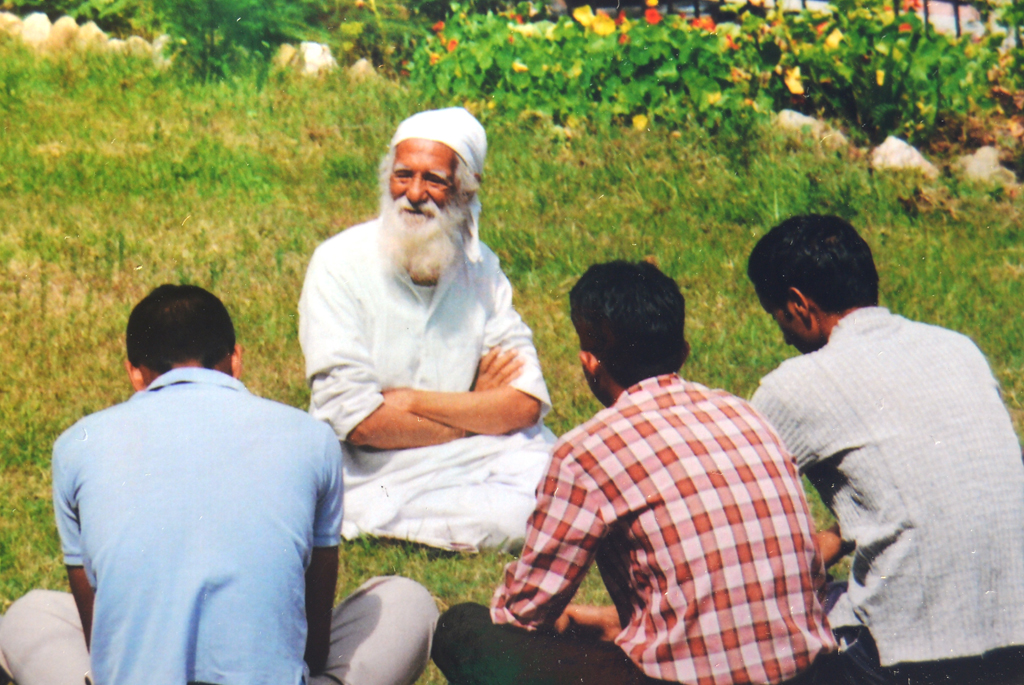

Sunderlal Bahuguna at New Tehri Sunderlal Bahuguna (9th January, 1927-21st May, 2021), the chief leader of Chipko movement was a true follower of Gandhian ideology and joined in the Indian freedom movement under the leader-ship of Shridev Suman, an ardent Gandhian follower who strongly believed in the premise - Charkha as the sign of soul force for bringing Indian independence. In 1944 i.e., in pre-independent period Bahuguna was arrested by the British Government when he wrote in the newspapers against the torture inflicted, in jail, upon Shridev Suman who was arrested when he protested against the king’s repression in Tehri Garhwal. Though Shridev Suman was died in jail after a long fasting for 84 days, Bahuguna was shifted to the Nagendra Nagar jail where he was fed food with a mixing of Kerosine oil and become seriously ill. However, he was released, on conditioned, from the jail custody after the advice of the doctor to the jailor. Later on, i.e., in post-independence period, he spent his entire life for saving the ecology and thus become a real ideal environmentalist for saving the mother earth by heart and soul following the path introduced by Gandhian ethics. This article is, actually, an elaboration cum analysis of the works done by Sunderlal Bahuguna, reflected on the mirrors of environmental ethics, especially, Gandhian ethics following these subsections: (i) Environment & its meaning, (ii) Environment and Western Ethics (Anthropocentricism, Non-anthropocentricism, Land ethics of Aldo Leopold & Deep Ecology of Arne Naess), (iii) Environment & Indian Tradition, (iv) Gandhian ethics, (v) Major environmental activities of Sunderlal Bahuguna, (vi) Conclusion -Sunderlal Bahuguna an architype of Gandhian ethics. (I) ENVIRONMENT & ITS MEANINGBefore delving the ecological-activities done by Sundarlal Bahuguna, let us take a glance what is meant by environment, its relation to the nature, its crises and the ways to resolve the environmental crises both from the Western as well as Indian tradition. Though the term 'environment’ comes from a French word 'environ’ or 'environner’ which means 'around’, 'to surround’ etc.; it is used to describe everything that surrounds an organism and thereby the term 'environment’ may be defined as 'the total of the things or circumstances around an organism including human beings’ or in other words, 'the circumstances or a condition by which one is surrounded.’ The term 'environment’ has been used in two senses - narrow and broad. From the perspective of narrow sense, the meaning of the term environment is restricted within a particular sector. For example, the environment of a school or a college or a university whereas, in broad sense, this term includes each and everything of the universe including the human beings. Side by side, the term environment is the reflection of a harmony among all the stake holders of this universe whether it is animate or inanimate entity. That’s why the Indian sagacious Rishis introduced the Gyātri Mantra, the greatest Mantra of the universe by incorporating the line Om bhur bhuvah svah where OM stands for the completeness, the Infinite, the Perfect and the Eternal. In fact, the completeness and the wholeness of all things are represented by the very sound OM. Not only that we have learned from our sacred sagacious teachers that the meditation should begin with OM and, end with OM in order to feel that the finite mind has the power to realize Infinite, Completeness as well as to be emancipated from the world of narrow selfishness. In the line Bhur bhuvah svah, though the term bhuh represents this earth, bhuvah represents the sky and svah represents the starry region respectively, the whole sentence is the reflection of the realization of that noble feeling - 'you are born in the Infinite, that you belong not merely to a particular spot of this earth, but to the whole world.’1 In fact, Nature provides sufficient wealth in order to be survived in a symbiotic manner, but disproportionate use of the natural wealth seems to be the main cause of environment degradation. We have the natural resources but these resources are not unlimited, it is the proportionate use of the natural resources which is the ultimate principle of the equilibrium in nature. But we have failed to do so, as a result, we have been in different types of environmental crisis such as Green House Effect, Destruction of Ecosystem, Loss of Bio-diversity, Shrinking Glaciers, Rising Sea Level, Drought, Storm, Flood, Heat Waves, so on and so forth. (II) ENVIRONMENT AND WESTERN ETHICS (ANTHROPOCENTRICISM, NON-ANTHROPOCENTRICISM, LAND ETHICS OF ALDO LEOPOLD & DEEP ECOLOGY OF ARNE NAESS)The discussions mentioned above, however, present what we, the Indians, have learned about the environment from the teachings of our ancient sagacious sages, are basically the reflection of coexistence as well as the unification, on the basis of intrinsic value. Whereas, in Western thoughts, the environment is treated from utilitarian perspective where instrumental relationship has been given priority and thereby the human beings have learned how to bypass their strong moral obligation towards the nature. The reason of this attitude, taken by the Western thinkers, perhaps, based on the dualistic philosophy propounded by Descartes, who considered, the whole world as a machine which is to be controlled by the human beings. This Cartesian mind and body dualism also leaded the scientists to believe that the matter was dead and completely separated from the living beings. And the material world is a multitude of different objects assembled into a huge machine. Such a mechanistic world view was also adhered by Sir Isaac Newton who constructed his mechanics on its basis and made it the foundation of classical physics which dominated the scientific world. But this type of scientific attitude, compels the human beings to create a distinction between we and the other and thereby to think, in order to live in, we are permitted to use the limited natural resources disproportionately. However, in order to cope up with the above-mentioned environment crisis, from the Western perspective, the environmental ethics developed and thereby the nature has been evaluated from the perspective of anthropocentricism as well as non-anthropocentricism. Those who believes in anthropocentricism are in the opinion that as human beings are rational and they are in the top, everything except human beings are for the human beings. The anthropocentric attitude towards nature has been supported by Aristotle, Rene Descartes, Sir Isaac Newton and Bible. Aristotle’s chief concern is this: in the natural hierarchy, the less reasoning ability exists for the sake of those who have more. Again, when Descartes announced that the whole world was a machine and human beings were the propellor of this machine, human beings thought that they have no direct responsibility for the nature. Sir Isaac Newton, being a great scientist has also been influenced by such a mechanistic world view in order to make the foundation of classical physics which is dominated by the scientific world up to the nineteenth century. Again, in the biblical story of creation, it was clearly mentioned that human beings had a special place in the divine plan. On the other hand, those who are non-anthropocentric, strongly believe that each and every entity of the world has an intrinsic value whether the entity is human being or not. This non-anthropocentricism has been supported by many environment moral philosophers. Among them Aldo Leopold (1887-1948) is treated one of the best moral philosophers in the history of environmental moral philosophy. His collective essays published posthumously as a Sand Country Almanac (1949) brings a new movement in environmental moral philosophy. In a book chapter - 'Land Ethics’, he argued for the extension of the morality among non-human beings. He claimed that once upon a time, it was not morally wrong to hang the slave, as the slaves were treated as the property of the owner and they had no moral right. In his writing, he presented an example, where a dozen number of slaves were hanged by a slave owner named Odysseus, due to the misconduct and no protest was raised against such type of inhuman activity done by Odysseus. But at present, the morality has been extended to the all-human beings including the slaves, children and the disabled. In this context, it is noteworthy that John Lock treated the land as a dead property, on the basis of which we, the human beings have been thinking that we could do anything with the land in order to fulfil our unlimited desire; but, in future, due to the extension of morality, we should reconsider land as a living organism instead of treating it as a dead property due to the extension of morality. According to Leopold, however, it would be wrong, from the perspective of human being, to conceive the land as a mere soil. Land is neither mere soil nor the property of human beings, rather we should realize it as the source of energy that spontaneously flows from the land. He remarked, “Land, then, is not merely soil; it is the fountain of energy flowing through a circuit of soils, plants, and animals.”2 This means he actually extended the ethics and, in this connection, he said, '...the land ethics simply enlarges the boundary of the community to include soils, waters, plants, and animals, or collectively the land.’3 He then said, though we were yet to form a land ethics in true sense, the works had already been started in the form of moral right which was extended up to the other species in the form of the endangered species. While Leopold has been developing his moral perception about land ethics, said, '…a land ethics implies respect for fellow members and also for the community as such.’4 From this, it seems that he preferred an ethical holistic dimension towards the environment, because it is most practical, it is complementary with epistemological holism inherent in ecology and it acknowledges the metaphysical reality of ecology as a whole. In fact, for him, the whole environment is actually a living organism where each and every part of these living organs is valuable, at least from the perspective of morality, integrity, stability and beauty. Arne Naess, being a Norwegian professor of Philosophy, the first chairperson of Green Peace in Norway and an ardent follower of non-anthropocentricism felt the ecological crises in the same way as paved by Leopold; but his solution towards environmental crises was deeply rooted into the inner relationship among the stakeholders of the environment and thus he introduced the notion of deep ecology. In order to understand deep ecology, we must compare it with the idea of shallow ecology. Shallow ecology is concerned with the welfare of human beings after the considering the extension of morality towards the non-human entity. It is in fact a weak form of anthropocentricism. But in case of deep ecology, according to Naess, '…rejection of the man-in-environmental image in favour of the relational, total field image. Organisms as knots in the bio-spherical net or field of intrinsic relationships hold between two things. An intrinsic relation between two thinks A and B is such that the relation belongs to the definitions or basic constitutions of A and B, so that without the relation, A and B are no longer the same things. Thus, we think that the total-field image dissolves not only the man-in-image environmental concept, but every compact things-in-milieu concept except when talking at a superficial or preliminary level of communication.’5 So, from the deep ecological perspective, Naess also taken almost the same holistic view towards the environment as like as Leopold, but the difference between Leopold and Naess is lied in the fact that Leopold depended on the argument of analogy, whereas Naess favoured the argument of intrinsic relationship among the different members of the environment. The inherent relationship, among the biotic and a-biotic components of the environment, is the rudimentary of deep ecology. He considered an individual, from the perspective of environment as well as social, as a knot in a holistic fabric stitched together by the thread of intrinsic relations which is reflected in the human societies when they make an attempt to extend diversity, complexity, autonomy, decentralization, symbiosis, the principle of 'live and let live’, egalitarianism and classlessness. From his contemplation, the ecosystem is an environmental system of philosophy where ecological justice, in the real sense of the term, can be protected as well as preserved and thereby not only the equal right to live and blossom for everyone is ensured but also it has been guaranteed that no being is a subject of getting morally privileged position compared to others. What is good for the whole is equally good for the individual. That means individual or atomic goodness does not make any sense without preconceiving the good of the whole. He also said that individuals’ identity depends only in terms of whole. (III) ENVIRONMENT & INDIAN TRADITIONAncient Indian concept of environment, on the other hand, was based upon the harmony among all the stake holders of the universe. What the present Western environmental philosophers have thought about the environment, had already been reflected in the feelings of the ancient sagacious thinkers as the traditional Indian culture, religion, values and philosophy were very strong, rich and non-anthropocentric. This type of non-anthropocentric thinking has been documented in the first stanza of Isho Uponishad as follows: Ishā basyamidang sarbang Yat Kincha Jagatang Jagat | It signifies that “The whole universe along with its creatures belong to the Lord (nature) and consequently to nature (Prakiti). Implicit in this philosophy is that none of the creatures is superior to the other and each has its own place and function in nature mosaic. Thus, human kind should, in no way have absolute power over nature. Let me one species encroach upon the rights and privileges of the other. Give up avarice and enjoy the beauties of nature.” The literature review on Rigveda and other similar works shows that the ancient Indians were very much ardent and critical investigators in order to protect the plants and their proper utilization. They also believed in the interrelationship among different kinds of matter, plants, living beings, matter and plant, matter and living being, plant and living being, and matter and plant and living being. Padma Purana says that the primitive staff of the universe are Khiti, Ap,Tej, Marut and Boyom i.e. soil, water, fire, wind and sky and if there were no inter relationships these elements, there would have no life in the universe and the living beings of the Planet would have been on the verge of extinction. Ancient India was terribly concerned about preservation of the plant’s life, wild life and bio diversity within all ecosystems and ecological composites. That is why the Rishis prayed “ihaitu sarvo yah pasur asmin tisthatu yā rayih”7 - “Let every beast whichever is there of the animal world which comprises wealth (rayih), come hither and stay with us”. In ancient Indian tradition, all the animals were considered as natural wealth, fit for protection and conservation. For this reason, the Mahabharata has repeatedly declared: “Ahimsa Sarva-bhutebhyo dharmebhyo jyāyasī matā”8 , i.e., non-injury (love) is known to be the highest virtue for all persons. (IV) GANDHIAN ETHICSIn order to understand Gandhian ethical view point, let us start from the Gandhian notion of Truth. Though, in 'Young India’ Gandhiji upholds - 'Truth is God.’, initially, young Gandhiji has a firm conviction on 'God is Truth.’ These two statements are not, however, interchangeable, according to Gandhiji, because the earlier statement - 'Truth is God.’ is more fundamental, philosophical as well as spiritual. The statement - 'God is Truth.’ has been introduced by Gandhiji to serve a purpose -in order to get rid of the sacred Indian religious tradition where the God has been called by many names. These many names of the God are not only the reflections of divertive Indian cultures as well as religions but also show how the Indians are conscious to make a close relationship with the God. In fact, Gandhiji, for the sake of unification, at the time of his youth, calls 'God is Truth.’ That’s why Gandhiji remarks, 'In my early youth I was taught to repeat what in Hindu scriptures are known as one thousand names of God. But these one thousand names of God were by no means exhaustive. We believe and I think it is the truth that God has as many names as there are creatures and, therefore, we also say that God is nameless and since God many forms we also consider Him formless, and since He speaks to us through many tongues, we consider Him to be speechless and so on.’ (Young India) It is quite reasonable to raise the question like this: what is the underlying compulsion of Gandhiji through which he firmly adopts 'Truth is God.’ instead of 'God is Truth.’ The God may be equated with the Love also as the Christian religion as well as the Islam religion prefer to equate the God with the Love. But Gandhiji considers this inappropriate, as in English language the term 'love’ has many meanings amongst which it sometimes designates the passion which, is the mark of degradation. When Gandhiji pays a firm conviction on 'Truth is God.’ it signifies how Gandhiji has been influenced by Indian philosophical traditions where the Reality i.e., Sat has been reflected by the term Truth. It is not just a clarification of either Truth or the God, rather it is the depiction of the God, the essence of religion through the essence of Reality or Sattva or Existence. 'Truth is God.’ is the mark of a coordination between philosophy and religion as well as Reality and its beyond. This relationship between the Truth and the God could be understood only when a person gets an 'inner call’ of - 'what the voice within tells you’ through the enlightenment based on the following ways -the vow of truth, the vow of Brahmacharya (purity), the vow of non-violence, and the vow of poverty and non-possession. On the basis of the notion of the Truth adopted by Gandhiji let us peep into Gandhian ethics. Though Gandhiji is fully aware of the Western teleological and deontological ethics, he has rejected these theories as these are devoid of showing the conformity between means and actions.9 The utilitarian moral principle - 'greatest good of greatest number’ does not guaranty to generate good result from good action, because bad action may sometimes produce the good result. In other words, a good end is the result of a good means is not guaranteed by the utility principle. That is why, Gandhiji, in his entire life even at the time of any movement whether in South Africa or in India, never allow any type of technique based on malpractices. Again, he does not go with the deontological ethics of Kant who argues for self-imposed universal moral law which is not concerned with the result of the action. For Kant, the means being final, the result is irrelevant; as his slogan is - 'Duty for duty sake.’ But, Gandhian ethics, as has been said earlier, never ever permit the separation of means and ends. In fact, what Gandhiji talks about moral principle, is neither reflected in the utilitarian moral principle -'greatest good of greatest number’ nor reflected in Kantian principle of morality - 'Duty for duty sake.’ as it is -'greatest good of all’. Though the utilitarianists believe in the moral principle - 'greatest good of greatest number’, in order to apply this principle, we are to follow some external and internal moral sanctions. Kant also favours the inherent conviction on the conscience along with the formal moral principle - 'Duty for duty sake.’ of the individual in the corporeal field. But Gandhian principle of morality - 'greatest good of all’ requires true self-sacrifice as it is linked with the application of soul force which emerges out of the strong and unconditional faith on the Truth and the God. That’s why Gandhiji remarks, as 'greatest good of all’ is the ideal principle of morality, we should never compromise with the ideal, though it has been pitched high. Not only that this principle 'greatest good for all’ does not allow any type of depressive attitude if any one failed to achieve the ideal, because the unattainable ideal stirs up greater and greater to make unending effort in order to progress towards it. In order to apply this principle 'greatest good for all’, Gandhiji depends on two fundamental great virtues of social human beings which are ahimsa and love. Aristotle, the great Greek philosopher also preferred 'Virtue Ethics’ as he believed, it is the manifestation of the virtues through which human being could lead a good life.10 Though in Aristotle’s ethics ahimsa and love have been considered as fundamental virtues, Gandhiji has been influenced by the Jaina and Vaisnava systems of Indian philosophy. Because ahimsa, for the Jaina, means 'non-injury in thought, word and deed, including negative abstention from inflicting positive injury to any being, as well as positive help to any suffering creature.’11 Again, love for the Vaisnava designates the relationship between the God and the devotees through the forms(rasa) of Śānta, Prīti, Preya, Vatsala and Madhura.12 For Gandhiji, ahimsa is very simple as well as natural quality for human being when she or he considers ahimsa from the perspective of sensual impulses. But human beings have other additional aspects also -the aspect of rationality and spirituality. Sensual aspect is the reflection of selfishness of a man, whereas rational aspect, though not selfish, is guided by utility. When a man realises, neither the sensual aspect nor the rational aspect is fit for reaching the goal, he applies his spiritual aspects and realizes the power of ahimsa and thereby understands, it is Love through which one can win anything whatsoever. After getting an inner call, the narrow selfishness as well as the utilitarian attitude are vanished. 'Love helps a man to break the barrier between self and others. When a man is unaware of his real nature, he may be led by the impulses. But after the realisation of his real nature -he is inseparable from others; his ego is vanished. The path is not too easy, and it is achievable through the moral knowledge which enables the transformation of ahimsa in to the love.’13 For Gandhiji, Truth force or the Soul force is the main force though this force does not depend on any type of arms, rather it depends on Love. He has a strong conviction that Truth force, Soul force and Love force are same as like as the mathematical truth 7+5=12. In order to support his view, Gandhiji has put forwarded an excellent argument. Though the Englishman believe in the proverb -'a nation which has no history, that is, no wars, is a happy nation’, Gandhiji counter this proverb by saying, in that case, human species would have been extinguished, because of the war; as there is another proverb 'Those that take the sword shall perish by the sword.’ In this regard, Gandhiji has also found a peculiar characteristic of the media where the conflicts of two nations are given priority, instead of the peace full living of the two nations based on Love force. In fact, India is not a country which believes in any kind of war as it has a prolonged history based on ahimsa or non-violence. In a crisis period of Vedic civilization, Buddhism emerged in 6th Century B. C.E., which made a stir in the Universe. From Lord Buddha (566 B.C.) to Shri Shri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu (1486 A.D.E.), India followed a humanitarian and philanthropic way for the salvation of mankind. Not only that India always tootle the tune of ahimsa or non-violence for the rest of the world and this noble path paved the way for other nations. This has been proved when the great ruler Asoka, in the 3rd Century B.C.E, followed this way and was success full in all respects. Gandhiji further says that this Truth force or Soul force or Love force is not just formal, it has a practical applicability when it is used to fulfil the purpose of the Passive Resistance. In case of Active Resistance, the use of arm force is necessary, whereas in case of Passive Resistance, what is necessary is the application of Truth force or Soul force or Love force. An example, may be helpful to get the point. Suppose the Government, impose a law which I do not favour. In order to repeal the law, I may use my arm force against the Government or, I may be arrested as well as punished when I disobeying the law, by the Government. In the second disjunct, of the earlier statement, the application of Soul Force or the Passive Resistance has been reflected. In a single sentence, Truth force or Soul force or Love force or Passive resistance may be expressed as 'It involves sacrifice of self.’14 In fact, the sacrificing of the self through the application of Love force has the power in bringing the changes of inner self of any person who ever he or she may be. It is an historical evident that Angulimāla, the cruel bandit was changed totally through the application of Love Force by the Lord Buddha. (V) MAJOR ENVIRONMENTAL ACTIVITIES OF SUNDERLAL BAHUGUNAFrom these back ground, let us flash back upon some of the major works done by Sunderlal Bahuguna who being an ardent follower of Gandhian moral philosophy, strongly protested when the Himalaya, the Ganga and Bhagirathi these three living organisms of the earth were about to be killed by the state. Being a man of action, not a man of book, pen and pencil; he knew (i) how to fight against the coercion imposed by the state whether in pre-independent India or post-independent India through Satyagraha; (ii) how to keep firm conviction on the power of common man, especially, the women; (iii) how to complete a long march about five thousand kilometres for the sake of the protection of green as well as ecosystem; so, on and so forth. Being inspired by Shridev Suman, an enthusiastic Gandhian follower Bahuguna joined in the Indian freedom movement. In 1944, Bahuguna was arrested when he wrote in the newspapers about the torture inflicted in jail upon Shridev Suman. When Bahuguna was shifted to the Nagendra Nagar jail where he was fed food with a mixing of Kerosine oil and became seriously ill hard the news of death of Shridev Suman after a long fasting of 84 days. Due to serious illness, Bahuguna was released from the jail, on conditions. In pre-independent period, at the time of organising adult education classes, especially, for the needy, destitute as well as untouchables, and protesting against liquor vends; Sunderlal Bahuguna got in touch with Gandhi’s two well-known European disciples -Mira Behn and Sarla Behn. However, he married Vimla Nautiyal, a co-worker of Sarla Behn in the condition that they would lead their ashramic life, among the rural people, in the village, renouncing the political life. Later on, i.e., after independent, Bahuguna transformed himself as a green man. In March 1973, when the Government of Uttar Pradesh decided to auction the ash trees in the Himalayan range for the sports manufactures, the local people protested against such type of decision made by the Government. Bahuguna understood such type of decision made by the Government, could not be repealed unless and until the movement took the shape of national or international level movement. That is why he undertook a padayatra, as he knew very well that massive deforestation would be the cause of ecological disbalance which would ring the death-knell of the Himalayas. Not only that he directed this movement in such a way which was not only unique but also the exploration of a close relationship between the trees and human beings, and it is categorized as the world’s first successful environmental movement through the path of ahimsa, shown by the Gandhiji as well as our forefathers. When the business minded and immoral contractors came in the spot with the armed police, hundreds of women hugged the trees as if these trees were their own sons. No power of the world could separate them from their sons. Sunderlal Bahuguna remarked, “Though it began as an economic movement to articulate the basic demands of me locals, it acquired an ideological impetus when the havoc wrought by the felling of trees began to tell upon the ecosystem in the form of landslides and floods.” In order to bring the deforestation to the public attention, during 1981 to 1983, Sunderlal Bahuguna led a 5000 kilometres long march across the Himalayas. It caught the attention of the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, who immediately took steps to pass a legislation to protect some areas of the Himalayan forests from clear-cutting. Let it be noted that in 1981, the UP government was also compelled to ban of felling of trees above an altitude of 1,000 metres. Being the successful leader of this Chipko movement, he became internationally famous and got plenty of awards as well as international invitations. Amazingly, this apostle of the mother earth declined the prestigious award 'Padma Shri’ in 1981, as he thought that it was his duty to save the earth, actually, he was beyond of any material reward. In this year, when he was invited to the United Nation energy conference held in Nairobi, he drew the attention of the world’s citizens after he marched to the conference centre with a bundle of firewood on his back. In fact, it was a symbol of fire which was in the heart of Bahuguna in order to protect the ecological balance of the mother earth. His attitude towards the world’s citizens may be expressed as -'I am of the ecology; I am by the ecology and I am for the ecology.’ However, the Chipko Movement received the Right Livelihood Award which is referred to as the Alternative Nobel Prize in 1987. The power of Satyagraha, has been applied by this environmentalist again during 1978-2004, when he was informed that Tehri Hydro-Electric Dam Corporation was about to cease the life of two lively-lovely rivers -the Bhagirathi and the Bilangana, the source of the holy river Ganga through the Tehri Hydro-Electric Dam project. Initially, an organisation named as Tehri Bandh Virodhi Sangarsh Samiti (TBVSS) started its anti-dam movement from January, 1978 through massive demonstrations in Tehri town; but most of its members were arrested by the police on the basis of court order. Over the years, as the movement was failed to channelized in a right way, the work of building dam has been on its own way. When Bahuguna joined in this movement, this movement was recharged. Bahuguna and his followers were arrested as the contractors were failed to resume any blasting works for building the dam due to dharna. Though the dharna slow down the dam building work, it was not enough to stop the work. That is why Sunderlal Bahuguna firmly decided to stop the project and thereby to save the lives of these two rivers which have been flowing since thousands of years through the weapon of fasting based on soul force. In 1995, he started his first phase of fasting, into a tattered tent, at the bank of the river Bhagirathi where the project work had been going on; while huge trucks and dumpers, belonging to Jaiprakash Associates, the contractor of the said project, continuously making noise for twenty-four hours as they were convinced that no power on earth could stop their project work. After a long fasting for 45 days when Bahuguna, at the age of sixty-three, was in the skin and bone after losing a weight of ten kilos, the then Prime Minister P.V. Narasimha Rao ordered to withheld the dam building project for a while and made a committee in order to review whether this project goes against the ecological balance or not. When he was failed to get any fruitful result through the promise made by the Prime Minister P.V. Narasimha Rao, he went on second phase of long fasting for 74 days at Gandhi Samadhi, Raj Ghat. At that time, the Prime Minister was H.D. Deve Gowda. Getting a positive signal from H.D. Deve Gowda that he personally reviewed the project, Bahuguna broke his fasting. But Jaiprakash Associates resumed their work in 2001, after a court case which ran in the Supreme Court for over a decade. However, in 2004 when the dam reservoir started filling up, on 31st July, 2004 Sunderlal Bahuguna was finally shifted to a new accommodation at Koti and later on, to Dehradun i.e., his own house. (VI) CONCLUSION -SUNDERLAL BAHUGUNA AN ARCHITYPE OF GANDHIAN ETHICSFrom the abovementioned successful two major environmental activities done by Sunderlal Bahuguna, it is clear that he was not a man of words, but a man of actions. He not only realized 'you are born in the Infinite, that you belong not merely to a particular spot of this earth, but to the whole world.’ what Tagore talked about the nature, but also acted as the modern Bhagiratha who saved the Himalaya as like as the ancient Hindu Mythological Bhagiratha who saved the earth by bringing the Ganga. There is no direct evident whether he was firmly concerned about the Western ethics i.e., Anthropocentricism, non-anthropocentricism, the 'Land Ethics’ of Aldo Leopold & the 'Deep Ecology’ of Arne Naess; Sunderlal Bahuguna’s works, in order to preserve the ecological balance, are the manifestations of the profound Western ethical theories - 'ethics for the environment’, 'ethics of the environment’, 'Land Ethics’ of Leopold as well as 'Deep Ecology’ of Arne Naess. Again, the attitude of the ancient Indian sagacious teachers, for the environment, have also been reflected in the works of Bahuguna as he believed that each and every part of the universe as valuable wealth which are subject of preservation, for sake of preservation, not from any kind of utilitarian and/or scientific perspective, but from moral perspective. In fact, the source of Sunderlal Bahuguna’s activities were a precious 'optical prism’ where any type of ethical theories whether from Western perspective or from Indian perspective can be reflected. However, none can deny that most of his activities were grounded on Gandhian ethics. He was, actually, the archetype of Gandhian ethics. From the pre-independent period his works proved that he had a firm conviction on Satyagraha, Fasting, March through the path of non-violence. In Chipko movement as well as in Anti-Tehri Dam movement, being a leader, he got huge support of mass. He could have shown his physical power to the Government, as the number of armed persons were limited. But he never followed that way as he had a firm conviction on non-violence. Following Gandhiji he also strongly believed that history is not just the records of war fought between two Kings or Powers through the river of blood. History could be written for the simple, general and common people through the path of non-violence and he proved this by giving the leader-ship of these two movements -the Chipko movement as well as Anti-Tehri Dam movement where hundred of general people, especially, the women were heroes or heroines, respectively. A leader becomes a true leader when he stands in front of the battle field. Sunderlal Bahuguna, being a true leader went for two phases of fasting (45 days & 74 days) when he crossed the age of sixty. In fact, he revitalized his power by applying what Gandhiji called the Soul Force, the source of the power of a true Satygrahi. No words are sufficient to express his dedication at the time of leading a movement, it is really unimaginable to keep up the same spirit of leader-ship when the movement takes three decades in order to get the result. Sunerlal Bahuguna did this. Though he got Right Lively Hood Award in 1987 for Chipko Movement, Jamnalal Bajaj Award in 1986 for constructive work, Honorary Degree of Doctor of Social Science in 1989 conferred by Roorkee, Padma Vibhushan Award in 2009 for environmental conservation by the Government of India, his activities are, in fact, beyond of any material rewards as he was the apostle of that adorable Supreme Infinite being to whom we warship. He was a true archetype of Gandhian ethics. Though he passed away on 21st May, 2021 at the age of 94, his activities remind us the two important verses from the fourth Chapter of the Gītā: yadā yadā hi dharmasya glānir-bhavati bhārata | Whenever there is a decline of Dharma, O Arjuna, and an increase of Adharma, then I incarnate Myself. paritrān āya sādhūnām vināśāya ca dus kr tām | For the protection of the good and for the destruction of the wicked, for the establishment of Dharma, I advent myself from age to age.15 Notes and References

* Dr Rajkumar Modak, Professor, Department of Philosophy, Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University, Purulia, West Bengal | Email: skbuphilosophy@gmail.com. |