Some men changed their times...

One man changed the World for all times!

Comprehensive Website on the life and works of

Mahatma Gandhi

+91-23872061

+91-9022483828

info@mkgandhi.org

+91-23872061

+91-9022483828

info@mkgandhi.org

The evolution of Gandhi’s thoughtInsights into the Mahatma’s ideals based on his Hind Swaraj are revealing |

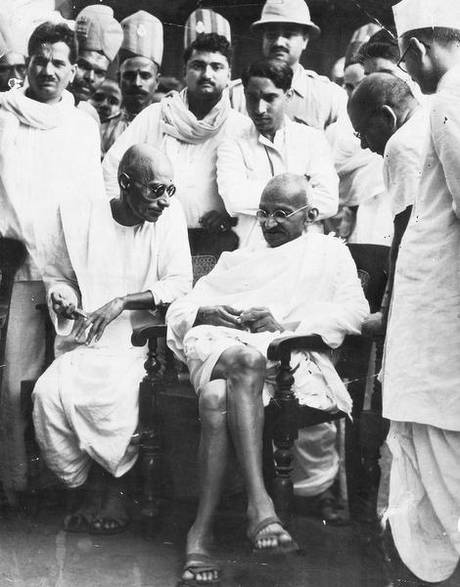

- By Irfan Habib* Mahatma Gandhi with C. Rajagopalachari at the Basin Bridge platform in Madras in 1940, before his departure to Wardha. The reader need not be reminded that it was in South Africa that Gandhi perfected the mode of Passive Resistance, which he later called “satyagraha”, to defend the interests of the Indian community in South Africa. During this period he was greatly influenced by the writings of Leo Tolstoy and John Ruskin: from the former he derived mainly his hatred of violence and consumerism, and from the latter, respect for labour and concern for the poor. But he took their critiques to apply to the Western industrial society alone, and held that old Indian society was free of the evils the West suffered from. This basic thesis was advanced in his Hind Swaraj, composed in 1909. The evils of western societies which India on obtaining Swaraj was to abstain from, as listed in this text, are startling: Electoral democracy was one such evil, for Parliaments were “really emblems of slavery”. Women were to have no employment outside the home: otherwise there would arise evils such as the suffragette movement in the West (demanding women’s right to vote). Above all, modern industry based on machinery was to be shunned. There were some faults in existing Indian society that he conceded, such as child marriage and polyandry, but no mention is made of polygamy or untouchability. The caste system is indirectly praised for having barred market competition by assigning a fixed occupation to everyone. It is proclaimed that India was being ruined by the three evils brought by the British, viz. railways, lawyers and doctors. He goes on even to say that rather than build cotton mills in India, India should continue to buy from Manchester! There was no need for compulsory education; “religious education” imparted by “Mullas, [Parsi] Dasturs and Brahmans” was enough. On the poorIt is remarkable that while Gandhi shows so much concern for the poor, he does not present any proposal in Hind Swaraj for the removal or alleviation of poverty itself. This is, perhaps, mainly because of his belief, unexpressed here but firmly held, in the sanctity of rights of property. As for political action for people to obtain what they legitimately wanted, ‘passive resistance’ was to be the means, to be undertaken, but only by those who “observe perfect chastity, adopt poverty, follow truth, cultivate fearlessness”. No further guidance on how India under Swaraj was to be governed is provided. The only modern notion adopted is that of ‘nation’, which, as in the rest of the world, says Gandhi, is not to be identified with any one religion. When Gandhi arrived in India early in 1915, these were his views, despite a reprimand over them from his chosen guru, Gopal Krishna Gokhale (d.1915), who had visited South Africa in 1912. Yet there proved in time to be a teacher for Gandhi, far severer than Gokhale, namely, the Indian poor themselves, for they too had ideas for their own salvation quite different from what Gandhi had chosen to prescribe for them in Hind Swaraj. The very first issue he encountered in India was that of untouchability, a matter ignored in Hind Swaraj. Immediately after he established his ashram at Ahmedabad in 1915 a crisis erupted when he admitted to it an ‘untouchable’ couple. But he withstood it, the couple stayed; and henceforth on this matter Gandhi would give no concession. If he yet went on affirming his faith in varnashram, this was done more or less to keep peace with the bulk of the upper castes. When Gandhi initiated his first popular agitation in India in 1917, namely, the Champaran struggle against indigo-planters, the issues raised certainly impinged on what the planters regarded as their proprietary rights; and in 1918 when Gandhi went on a hunger-strike in favour of striking textile mill workers, this could hardly be regarded as consistent with his own nihilistic attitude towards modern industry. Gandhiji’s ideas were put to test still more fundamentally during the Non-Cooperation movement, 1920-22. The main demand initially was for protection of ‘Khilafat’, a purely Islamic institution under the aegis of Ottoman Turkey, now threatened by the victorious Allies, Britain and France. This could well be justified by the invocation of religion as a legitimate source of political action, implicit in Hind Swaraj. But for larger mass support the demand for Swaraj was added to it; and this essentially meant drawing peasants into the struggle. Their role, however, could only be effective if they ceased paying rent to the landlords, who in turn would not then be able to pay the land-tax to the Government. But this struck against Gandhi’s notion of protection of property, and he specifically prohibited such action by peasants in U.P. through his “instructions” issued in February 1921. Yet peasants, especially in U.P., defied the injunction in many places. The village connectThe experience of the Non-Cooperation movement, led Gandhiji to formulate in 1924, his ‘Constructive Programme’. He had by now made his peace with electoral democracy by advocating optional universal suffrage for legislative bodies in an article in 1924. His Constructive Programme concentrated on work in the villages, involving the promotion of Khadi (hand-woven cloth out of hand-spun cotton), which was in line with his rejection of machine-made cloth, though here opposition to use of foreign, especially British, manufactured cloth was also involved. Allied with this project was a campaign for Hindu-Muslim unity and removal of untouchability. Simultaneously Gandhi developed his theory of the property-owners as custodians of the poor, the mill-owners looking after their workers, and landlords, after their tenants. This was part of an obvious bid to overcome class antagonisms. However, the approach was bound to have little practical consequence, since few Zamindars came forward to shower money on their tenants. When the next cycle of Civil Disobedience began in 1930, the acute distress of peasants owing to the Great Depression of 1929-32, tended to convert it largely into a peasant struggle. There was also now a growing industrial working class. To both peasants and workers the radical approach of Jawaharlal Nehru, himself greatly influenced by the Soviet Revolution of 1917, made a special appeal. Gandhi had already recognised the importance of Nehru as a figure commanding great popularity; and there is no doubt that he was now prepared to make concessions to Nehru’s approach. So came about his readiness to espouse Nehru’s draft resolution on Fundamental Rights, which Gandhi himself moved at the Karachi session of the Congress on 31 March 1931. This resolution established many principles in favour of which Gandhi had not yet pronounced, such as equality between men and women not only as voters, but also in appointments to public offices and exercise of trade: reduction of agricultural rent and levy of tax on landlord incomes, state ownership or control of key industries, and, finally, scaling down of the debts of the poor. Perhaps, Gandhiji later wished to draw back from some of what he had conceded (“a heavy price for the allegiance of Jawaharlal”, in the words of Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru). Thus to Nehru’s clear chagrin, he assured zamindars in U.P. that he would stand by them, if anyone attacked their rights; and when in September 1934 he resigned (formally) from the Congress, he cited as a grievance the rise of the “socialist group” in the Congress. Yet there is no evidence that he opposed in any manner the Congress Provincial Governments in U.P. and Bihar in 1937-39 when they framed their legislation restricting zamindars’ rights in relation to their tenants. Poona PactDuring these years, in fact, Gandhi chose for his main activity the welfare of the Depressed Castes, whom he now called Harijans. Provoked by the British Government’s Communal Award of August 1932, he went on fast against separate electorates created for depressed castes. This led to the well-known Poona Pact between depressed caste leaders, and caste Hindu representatives. Contrary to present-day denunciations of the Pact, it actually improved the representation of the Depressed Castes by more than doubling the seats reserved for them in the Provincial Legislatures, and providing 18% reservation (against none in the Communal Award) in the Central Legislature. There was also provision for an initial vote among Depressed Caste voters to select four eligible candidates for each reserved seat. The Poona Pact proved a signal for Gandhiji from 1932 onward to initiate a nationwide campaign against untouchability and for ‘Harijan’ uplift. Increasingly, Gandhi now avoided giving any sanction to the caste system, or any philosophical defence of varnashram. It is difficult to assess how much the experience of the Second World War II (1939-45) and the Quit-India movement of 1942 further altered Gandhiji’s social views. It is possible that he continued to cherish some nostalgia for a rural India, content with its poverty, as envisioned in Hind Swaraj, and a reassertion of the responsibilities of the rich as custodians of the poor. But, by and large, his rejection of the inequities of the caste system and of discrimination against women became only sharper. Above all, his concerns for Hindu-Muslim unity became ever more focused as he stood rock-like against communal violence that enveloped the country in the year of Independence. In his last great act, he went on fast in January 1948 to make India pay ₹Rs55 crore, the sum due to Pakistan, while both countries were at war with each other, and to get Muslims in Delhi back to their homes, from which they had been driven out. Here in practice, was a real assertion of internationalism and sheer humanity — for which he paid with his life on 30 January 30, 1948. It is fitting to remember that on the issue of communal amity Gandhi thus remained as firm till the end as he was at the time of writing Hind Swaraj. Courtesy: The Hindu, October 1, 2019. * Irfan Habib is an eminent historian and former chairman of the Indian Council of Historical Research. |