An Essay on the Thoughts and Deeds of J.C. Kumarappa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

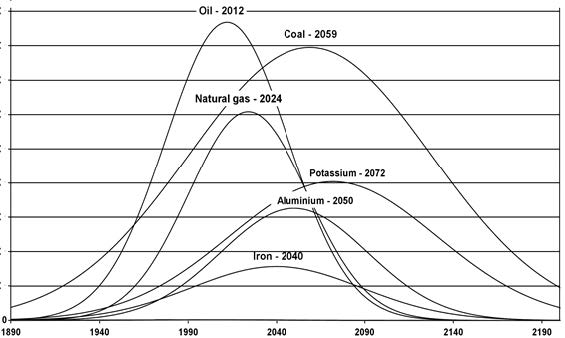

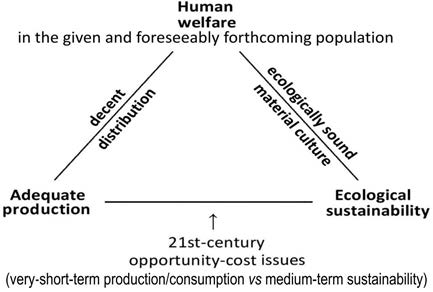

- By Mark LindleyAbstractJ. C. Kumarappa, an economist who followed the footsteps of Mahatma Gandhi, propagated ecological economics. His theory of ‘economy of permanence’ is mainly focused on ecological issues. He draws a clear distinction between renewable and non-renewable natural resources. According to him, our life pattern on the economy of performance paves the way for world peace, whereas the economy based on dwindling resources will lead to disharmony, unhealthy competitions, enmity and world wars. The paper strongly argues the need for ecological economics by placing Kumarappa as the champion of green economy, alternative development and decentralization of productive forces and polity. The article has also disclosed certain personal traits of Kumarappa. IntroductionOther Gandhians writing about economics focused on fair distribution of goods, but J.C. Kumarappa broadened Gandhian economic thought by paying a lot of attention also to ecological issues. His book titled, Economy of Permanence, implies an ecological outlook. He said: “Human life rarely reaches even a hundred years while ... to measure the life of Nature will run into astronomical figures... It is in this relative sense that we speak of ‘an economy of permanence.”1 He set out a clear distinction between renewable and nonrenewable natural resources: The world possesses a certain stock or reservoir of such materials as coal, petroleum [and] ores or minerals like iron, copper, gold, etc. These, being available in fixed quantities, may be said to be ‘transient,’ while the current of flowing water in a river or the constantly growing timber of a forest may be considered ‘permanent’ as their stock is inexhaustible in the service of man if only the flow or increase is taken advantage of.... Basing our life pattern on the economy of permanence paves the way for world peace, while the other [kind of economy, based on dwindling sources of consumable energy and raw materials,] leads to disharmony, unhealthy competition, enmity and world wars.2 Material reckonings (not at all the same as monetary reckonings) are characteristics of ecological economics. Kumarappa reckoned that 77,700 acres of land (66,600 in crops, plus some for “seed and waste”) could provide 100,000 people with a balanced vegetarian diet of some 2850 calories per day. Figure 1 shows a slightly simplified version of his table. Kumarappa did not disparage money. He said: “For transferring purchasing-power money and credit are unsurpassed.”3 But he added that an honest economic exchange should also include transfers of “human and moral values,” and that these are not represented inherently in a monetary transaction. (When we pay money to a person we can get some human and moral value into the transaction by (a) courtesy and friendly remarks and by (b) favouring “fair trade” purchases whenever feasible). Moral levels of Economic ActivityKumarappa posited a theoretical ladder of five moral levels of economic activity.

For example: “When a mother nurses her children, all the return she gets is the joy of seeing them well fed and happy; that is her ‘wage.’ From this [service-oriented economic activity] there is a fall to the ‘economy of enterprise’ when a wet-nurse feeds the baby.... When the extravagant claims [made on behalf of] of [synthetic] baby foods do not bear any close relation to [nutritional] facts, we go right down to the ‘parasitic economy’ where the profit made is the overruling consideration irrespective of any harm that may befall the baby.”4

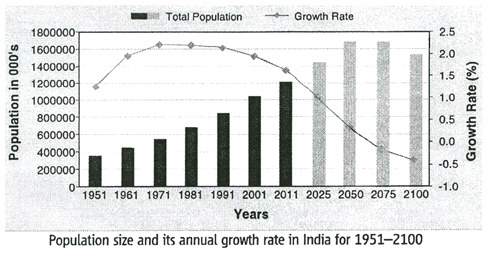

In his book Gandhian Economic Thought (1951)5 he distinguished between (a) “home industry” such as cooking or sewing for members of the same household, (b) “village industry” for distribution and consumption mainly within the same village, and (c) “cottage industry,” i.e. households producing commodities the consumption of which might take place anywhere. He saw that village industry is more efficient, transportation-wise and in terms of “transaction costs,” than are mass production factories. In the 1930s he had said: While the plant that transforms raw materials into consumable articles is located in some one place, the ... raw materials are gathered from the places of their origin and brought together to feed the machinery ... at a speed demanded by the technical requirements ... for production at an ‘economic speed’.... [And then] when the goods have been produced they have to be sold. Again the problems of routes, ports, steamships and political control of peoples have to be faced. Exchange, customs and other financial and political barriers have to be regulated to provide the necessary facilities. All this can be done only at the point of the bayonet.6 Need for Ecological EconomicsAlthough Kumarappa was less savvy about the natural sciences than 21st century environmental experts have to be, he had far more regard for chemistry and biology than market economists do. He urged (for instance) that government send out “soil doctors” all over the country to analyse local soils and advise farmers as to how much of this and that to apply by way of artificial fertilizer. Kumarappa could be tough. When Vinoba paid him a visit during the Bhoodan Campaign, his greeting was: “Here you are, the greatest thief in India.” Vinoba asked him to explain. He explained that (a) according to the Gita, if you have more than you need and do not share some, it amounts to theft, and that (b) Vinoba had secured donations of land but had not followed through to ensure that it was properly distributed. (Vinoba said: “Yes, now I understand.”) When Nehru visited him in hospital in Madras, Kumarappa handed him a sheet of paper with some policy recommendations, but then as Nehru was taking his leave he said to throw the sheet away. Nehru asked why; his reply was that since Nehru was going to do that anyway when he got back to New Delhi, he might as well do it now and save the trouble of reading it. I agree with T. J. Jacob’s recent assessment7 of Kumarappa as “one of the tallest and most original thinkers in the Indian independence struggle.” So, why didn’t Nehru pay more heed to him in the 1950s? Two of the reasons were his sharp tongue and the fact that the All-India Village Industries Association was not brilliantly successful. (It was a pioneering effort, and Kumarappa wasn’t a great manager.) But a bigger reason was that Nehru, whose studies at Cambridge University had been in Physics, Chemistry and Biology (some of each), believed – mistakenly – that the “neoclassical” economic theories guiding the Five-Year Plans were scientific and so the plans would succeed. But towards the end of his life, Nehru saw clearly that the Five-Year Plans had not represented a successful “tryst with destiny.” On several occasions in the early 1960s he said that Gandhian economics would have worked better. Recently, an 80-yearold social worker in Madurai, K.M. Natarajan, told me, for instance, that he personally heard Nehru declare, in a talk given in December 1963 in Tamil Nadu, that implementing the Plans had failed to abolish unemployment, poverty and hunger in India and that India could have done better by going “the Gandhian way” in economics (which in fact was Kumarappa’s way). A standard modern academic definition of economics (written in the 1920s by a professor at the London School of Economics) has been that it is the aspects of human behaviour that are “guided by objectives” (situated sometime in the future; you can’t have an objective in the past) and “deal with scarce means which have alternative [possible] uses.” About 150 years before that definition of economics was devised, one of the USA’s founding fathers, Thomas Jefferson (who wrote the Declaration of Independence in 1776), had said that “The God who gave us [humans] life gave us liberty at the same time.” (He declared that force could destroy them but could not “disjoin” them; they come and go together.) Let me now link up Jefferson’s insight with the modern British definition (that I have cited) of economics by pointing out that human behaviour is guided to a certain extent by deliberation, and therein lies our natural liberty” (which Jefferson called a gift from God): We humans have not only will-power (as do a lot of other animals), but deliberative will-power. We talk with each other and deliberate as to how to try to attain certain objectives by using more-or-less scarce means – resources of one kind and another which have alternative possible uses. (And if we use up a certain set of resources to attain “Objective A,” we thereby sacrifice the opportunity to use them to attain “Objective B” instead. The economists’ name for this kind of sacrifice is “opportunity cost”.) Kumarappa observed: “The main trouble with Man arises out of the fact that he is endowed with a [so-called] ‘free will’ [i.e. deliberative will-power] and possesses a wide field for its play.”8 His point was that: “By exercising this gift in the proper way, he [that’s us] can consciously bring about a much greater cooperation and coordination of Nature’s units than any other living being. Conversely, by using it wrongly, he can create quite a disturbance in the economy of Nature, and, in the end, destroy himself.”9 Let me outline briefly the ways that humankind is nowadays causing a precipitously destructive degradation of its natural environment. It is happening in more ways than you may have imagined: (1) Depleting earth’s “non-renewable” stock of fossil fuels at the present rate is bound to cause them all to be exhausted in a matter of decades from now. (The earth will make more coal and oil and natural gas, but that will take many millions of years, and we don’t have that kind of time at our disposal). (2) Depleting the stock of ores, and thus dispersing the earth’s economically valuable mineral resources (other than the fossil fuels) at such a rate that the cost, in terms of consumable energy, of reconcentrating and re-purifying them for repeated industrial use may well become prohibitive in a matter of decades. In Figure 2. below the bottom-left part of each curve shows when humankind began to extract from the earth, large amounts of the stuff in question; the top indicates what will have been the historical year of the “peak” rate of production if the rate winds down symmetrically to the way it went up; and the bottom-right point indicates when, a few decades from now, the bucket will be empty. The basic point is that when it is half empty it is only half full.  Figure 2. (Estimates based on proven reserves worldwide) There is a serious risk of wars, during the downward slopes, for what’s left in the bottom of the buckets. This is part of what Kumarappa meant by “unhealthy” competition. We had already such a war for control of the oil wells in Iraq. John Stuart Mill, a top British economist, argued for a “stationary state” – that is, with a stable amount of population and, supposedly, of capital stock. He said this would be compatible with moral and social progress; the economy could become better without getting bigger. He did not grasp that humankind, even if stable in numbers and in the rate of per capita use of resources, would empty out earth’s “buckets” of non-renewable natural resources such as coal. We cannot have a really sustainable way of life until it is all based on renewables. (3) Environmentally damaging displacements of H2O from glaciers to the ocean and of SiO2 (i.e. sand) from (a) beneath the topsoil in river valleys to (b) our pavements, walls, etc. A valley blessed with a river is naturally green because some of the water flowing in the river down to the ocean is diffused sideways through sand that is there beneath the soil along the river banks. The more sand is removed from beneath the soil, the more of the water will go directly down the river to the ocean, and thus less to the fields in the valley. (4) Using up the renewable natural resources faster than earth renews them. Some examples are the wood and greenery in many forests, the biotic micro-nutrient components of agricultural soils, rivers no longer flowing as far as the sea, and water-tables sinking deeper and deeper underground. (5) Climate changes that are beginning to play havoc with agriculture and to bring us more and more destructive storms. This will get worse. How much worse will depend on what is done soon to mitigate the amounts of “greenhouse gasses” in the air. (6) Polluting our soil, water and air: stocking them with excessive amounts of chemicals that are poisonous to eat, drink or breathe. amounts of chemicals that are poisonous to eat, drink or breathe. (7) Causing extinctions of biological species at a rate which could risk the survival of our own species (Homo sapiens) within a century or two. According to the Living Planet Index, global populations of fish, birds, mammals, amphibians and reptiles declined by 58 per cent between 1970 and 2012. According to a qualified ecologist, Peter Sale, by the end of this century: ...larger species (coyote size and up), other than those directly cultivated by humans, are likely to be extinct or to exist only as threatened populations.... Environmental goods and services [to humankind] will be much reduced simply because of the loss of diversity of organisms. With the increased homogeneity, there will be a much greater risk of pandemics that severely impact particular species and create massive change in ecosystem composition as a result. The risk of a species extinction that has major ramifications through the ecosystem will become ever greater as diversity falls, and our own population will be precariously dependent on just a few species to sustain its vast size.10 (8) Creation, by careless medical activities, of super-bacteria and increasingly virulent viruses. With poor luck we could be facing soon the end of the wonderful age (initiated 150 years ago by Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch) of effective anti-bacterial medicines. (9) And, geologists tell us that some of the recent earthquakes have been due to human agency! Nothing like this ever happened before. No one can predict the conditions forthcoming in the 21st century that will have been due to the combined, interacting effects of these various kinds of current environmental degradation. However, Figure 3. outlines succinctly a way of looking at the overall economic situation.  Figure 3. The need for ecological economics was starting to become urgent already 50 years ago, and this was understood by the most powerful politician in the world at that time. In the annual “State of the Union” Address given in January of 1970, he said that “the great question of the 70s” would be “Shall we make our peace with Nature and begin to make reparations for the damage we have done to our air, to our land, and to our water?” He established the US government’s Environmental Protection Agency and “Earth Day” as an annual government-sponsored day of celebration on April 22nd. (It is celebrated nowadays in more than 190 countries). But then came a persistent, lavishly funded political reaction against environmentalism and ecological economics, with Ronald Reagan in 1980-81, as candidate for the US Presidency and then as President, declaring that trees cause more pollution than automobiles do and that “80 per cent of airpollution comes not from chimneys and auto-exhaust pipes, but from plants and trees.” And meanwhile the Green Revolution was starting to make Indian agriculture depend in one way and another on fossil fuels – a precarious condition for a 21st century national economy. (India imports some 85 per cent of the petroleum that she consumes). And that use of Green Revolution techniques is now beginning to result in more fickle monsoons, dangerously depleted aquifers, and soils becoming depleted of biochemical micro-nutrients needed by the crops.  Figure 4. And yet, food-price inflation will be a problem in India as the population increases some 40 per cent from now to 2060. Figure 4. includes an expert demographic estimate of what the forthcoming 21st century population is likely to be if there is no vastly fatal pestilence, war or famine here. (For a rough estimate of the increase from now to 2060, consider that 125:175 = 5:7 = 100:140). But there won’t be more farmland or more overall rain in India then than there is now. And, converting more and more amounts of coal into smoke and dirty ashes would aggravate the global warming that is beginning to play havoc with the monsoons. So it seems to me vital for India to develop agricultural techniques which (a) will be less dependent on burning fossil fuels and wasting fresh water, and (b) will restore biochemical nutrients to the soils and offer greater crop yields (especially of vitamin-rich foods) already in the next few years. I hope that some of India’s best agronomists will focus on this tough problem, and those other first-rate technicians, and political scientists too, will focus on getting nutritious food conveyed more efficiently – without gratuitous damage to the environment – from the field to the plate. It is a tall order. I hope that some economists will respond adequately to the challenge. Economics of Social Darwinism or Economics of SolidarityMeanwhile if businessmen and women of the 21st century come to believe that they are morally obliged to prevent their work from aggravating the various kinds of precipitous environmental degradation that I have described, and if all the big national governments agree with that kind of thinking and feeling, then one result – in addition to some mitigations sooner or later of the material problems – would be a great deal more emphasis, in “business as usual,” on cooperation between firms and between nations than was sanctioned by the “Economic Man” Doctrine of late 19th and 20th century Western theory of economics. According to that Doctrine, economic agents are “rational” in such a way that each one “maximizes” his or her individual well-being with no priori concern for the welfare of anyone else. (According to the Doctrine, a mother does not really care for its own sake about her baby whom she is nursing etc.; she is doing it only for the sake of some later advantage). Some people doubt that a cultural change away from such venal selfishness can really take place. The “Economic Man” Doctrine rests on a persistent 19th century cultural notion: the “Social Darwinism” of Darwin’s popularizer Herbert Spencer (d.1903). According to Spencer, competition without cooperation is what determines the “survival of the fittest.” Biologists of the 20th century have shown, however, that cooperation permeates life on earth as much as competition does. For instance, the evolution, more than 1500 million years ago, from bacteria, i.e. single-cell organisms without nuclei, to single-cell organisms with nuclei was via “endo-symbiosis” (symbiosis within the body of an organism) between large bacteria and small ones which got inside the large ones but which the large ones could not digest. And here are some relevant anthropological facts – facts about human culture: Nearly 95 per cent of the 200,000-year history of homo sapiens predated the rise of agriculture, and during those many tens of thousands of years, people got an indispensable part of their nutrition from hunting big game – for which cooperation among the men was absolutely indispensable. Gandhiji would have been reluctant to accept the anthropological finding that it was carnivorous humans who rendered the species to cooperativeness (even though his own rejection of the Jain precept of absolute non-violence was due to his realization that agriculture entails certain kinds of himsa). But he would have been delighted in the anthropological finding that since human infants take so inconveniently long – compared to other animals’ infants – to learn how to walk etc., the tribes in which the women cooperated in looking after their children were the biologically fittest ones that became our ancestors. Most other big animals are far less disposed to give-and-take cooperation in small groups than we humans are. And, the fact that the men’s instincts to cooperate evolved originally in the context of violent activities does not mean that men can not cooperate in nonviolent undertakings. There is a gender-neutral aspect to the sociobiologically inherited capacity. I hope that just as people in, say, a nation, who mostly don’t even know each other personally, tend to pull together and cooperate more with one another if the nation is attacked by another nation than they do during peacetime, so humankind may perhaps pull together and change “business as usual” as the fact that we are all under sharp “attack” from “angry Mother Nature” becomes more and more clear. I am in my 80th year and so I will not live to see what the world is going to be like in the mid-21st century; but I know it will be very different from what it was like a few years ago. Your problems, and the possible solutions, will have to do not only with how humans relate to other humans, and with individuals’ capacities, but also with how humankind relates to the rest of Nature on Earth. ConclusionOur natural environment is now degrading more dangerously than ever before in the history of humankind. Economics needs to evolve, more and more in this century, towards ecological economics. So, the would-be new economists better study chemistry, as well as political science and other branches of group psychology. Let me mention here that John Maynard Keynes (the best 20th-century British economist), even though he did not foresee environmental problems regarded economic theory as “a science of thinking in terms of models joined to the art of choosing models which are relevant to the contemporary world”. He said: “It is compelled to do this because [,] unlike the typical natural science, the material to which it is applied is, in too many respects, not homogeneous through time.” In other words, we always need new economics. A lot of cooperation will be called for. We have in us a lot of cooperative instincts. The question is how well they will function under these new circumstances. Notes and References

Source: Reproducted from Gandhi Marg, Volume 39, Number 4, January-March 2018. Mark Lindely is Visiting Professor at Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Marathwada University, Aurangabad and author of 15 books including J.C. Kumarappa: Mahatma Gandhi’s Economist and more than 100 scholarly articles. After a career as a musicologist, he turned to Gandhi–Kumarappa studies. Email:marklindley1@gmail.com. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||