- By Rinchen Norbu Wangchuk

(Edited by Saiqua Sultan)

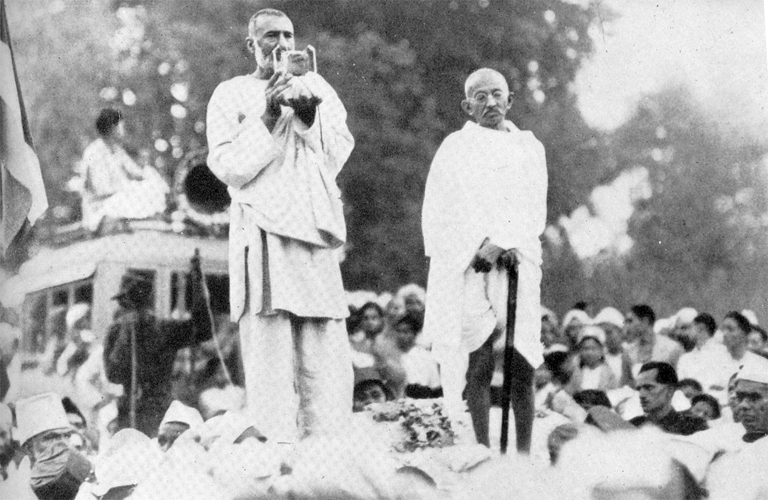

Gaffar Khan interpreting Gandhi's speech at a public meeting, NWFP (Afghanistan), October 1938.

Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, famously known as Bādshāh Khān, and Bāchā Khān, was a legendary Pashtun freedom fighter and pacifist whose greatness transcended all tribal and communal divisions. Though born and bred in a region infamous for its warring tribes and history of blood feuds—Pakistan’s North West Frontier Province (NWFP or modern-day Khyber Pakhtunkhwa), that borders with Afghanistan—Khan was a staunch follower of Mahatma Gandhi and his principle of non-violence. This love for ahimsa (non-violence) and Satyagraha (truth force) earned him another nickname, the Frontier Gandhi.

Born on February 6, 1890, in a prosperous Pashtun family of Utmanzai in the present-day Valley of Peshawar in Pakistan, the young Badshah Khan, after school, had sought to enlist in the Corps of Guides, comprising of British officers and soldiers serving in the NWFP.

However, upon learning about the second-class status these ‘Guides’ were afforded, he refused to join and instead went onto study at the Aligarh Muslim University. Holding hands with fellow Pashtun political activists, Khan joined the Independence Movement in 1911.

The region Khan came from suffered the worst forms of socio-economic oppression under the British, besides enduring a long and violent history of internecine bloodshed between different tribes – even as they continued to battle the British Indian Army.

Wanting to bring a change in the brutal way of life his brethren lived, Khan took up the task of uplifting the consciousness of his fellow Pashtun men and women through education. From 1915 to 1918, he travelled across some 500 villages in the Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa region, spreading the gospel of education, social reform and speaking out against a culture of violence in these communities.

However, his most notable contribution to the Independence Movement came after he first met Mahatma Gandhi in 1928 and his involvement with the Indian National Congress. Both men had a very close bond marked by shared principles and an astounding level of mutual respect.

Resonating with Gandhi’s ideas of nonviolence and Satyagraha, Khan founded the Khudai Khidmatgar (Servants of God) Movement after returning from his Hajj in Mecca. The Khudai Khidmatgars were also commonly known as the ‘Red Shirts’ (Surkh Pōsh).

What attracted the masses to Khan was his uncompromising integrity and total commitment to the path of non-violence and an unwavering belief in a united India.

The Khidmatgars actively participated in Gandhi’s Salt Satyagraha in 1930. On April 23 of the same year, the British India police arrested Khan along with many leading Khudai Khidmatgar protestors, after he gave a speech at Utmanzai urging resistance to British rule.

His arrest and the subsequent reaction of his supporters would garner the same response from the British as the peaceful congregation had in Jallianwallah Bagh in April 1919.

Unknowing of what was to befall them, a large group of supporters gathered at the Qissa Khwani Bazaar in Peshawar to protest the arrests. The British forces opened fire at the unarmed Khidmatgars, who, as a mark of their non-violent protest, stood willingly in front of the barrage of bullets.

While official figures cited 20 dead, unofficially the casualty count was into several hundred. Two platoons of the prestigious Royal Garhwal Rifles regiment refused to open fire at this non-violent crowd for which they were court-martialed and sentenced to prison.

Through the 1930s, the dauntless ‘Khudai Khidmatgar’ worked in close coordination with the Indian National Congress, and was once offered the party presidency, which he refused by saying,

"I am a simple soldier and a Khudai Khidmatgar, and I only want to serve."

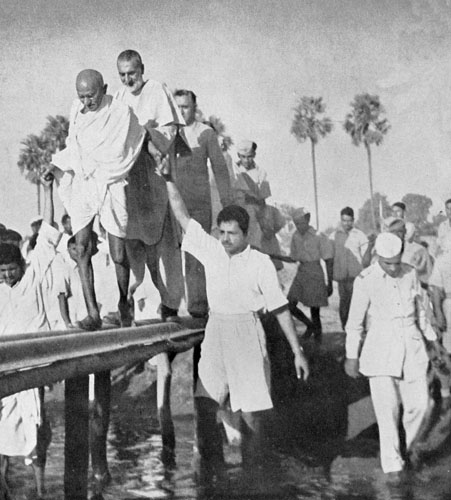

Gandhi with Abdul Gaffar Khan during the tour of Jahanabad, Bihar, March 28, 1947.

Khan resigned from the party in 1939 over differences with the party on whether they should support the British World War II effort or not but subsequently rejoined in 1942 with the onset of the Quit India Movement.

However, what followed, particularly in 1946 and the subsequent Partition of India, left him devastated. Leading the Khudai Khidmatgars, he firmly believed in the idea of an un-partitioned united India, where Hindus and Muslims would live together in harmony away from the tyranny of British colonial rule.

When the Congress acquiesced to the Muslim League demands for a referendum in the NWFP, thousands of Khudai Khidmatgars boycotted the referendum, which in hindsight may have been a strategic error since the results went in favour of the region joining Pakistan.

When his homeland eventually became a part of Pakistan, a decision accepted by both the Muslim League and Congress, he reportedly told the senior leaders of the latter, “You have thrown us to wolves.”

Following Independence, he asked the Pakistan government for the creation of “Pakhtunistan”, a semi-autonomous region for the Pathans within this new Muslim-majority nation.

This request was rejected.

Subsequent Pakistani governments branded the Khudai Khidmatgars as traitors and Indian sympathisers, considering their allegiance to Gandhian methods of non-violence and Khan’s relations with many Indian leaders.

They were often arrested, their lands confiscated and Khan himself was subjected to years in prison for protesting against the treatment meted out to the Pashtuns by the Pakistani government.

All the arrests – from late 1948 to 1954, in 1958 and 1964, and finally in 1973, had a detrimental effect on his health. From 1964, he would become an exile in Afghanistan.

He returned to Pakistan in December 1972 following the formation of provincial governments in NWFP and Balochistan led by the progressive National Awami Party. However, he was once again arrested by the Pakistani government in 1973 by the Bhutto government.

Despite being a citizen of Pakistan, Khan was held with a great deal of respect and reverence by the people and leaders of India. As he withdrew from active politics, he visited India on a few occasions. He was awarded the Bharat Ratna in 1987 by the Government of India for his contributions to the Indian freedom struggle and subsequently for better relations between the two countries.

"He and his brother saved Hindu and Sikh lives in the Frontier; he brought succour and relief to Muslim victims in Bihar; he confronted Jinnah in Pakistan and, twenty years later, India’s Parliament with uncomfortable facts of attacks on minorities. His fight for the rights of the threatened, the weak and the poor, his sympathy for peoples across the subcontinent’s borders, his scepticism about the effectiveness of guns and bombs, and his frankness towards both rulers and citizens make him an inspiring model," writes Rajmohan Gandhi, in his book ‘Ghaffar Khan: Nonviolent Badshah of the Pakhtuns.’

Undeniable proof of this was witnessed upon his death on January 22, 1988, in Peshawar. When his remains were taken to Jalalabad, Afghanistan, more than 200,000 mourners attended his funeral, including Afghanistan President Mohammed Najibullah and Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi. The government of Afghanistan had waived off the visa requirements, and for that day alone thousands crossed freely to attend the funeral procession.

"The burial in Jalalabad caused other unprecedented events. A one-day ceasefire was declared in the Soviet-Afghan war so that mourners could safely traverse the distance between Peshawar and Jalalabad, the two cities at either end of the Khyber Pass which marks the official boundary between Afghanistan and Pakistan," writes Mukulika Banerjee, author of ‘The Pathan Unarmed’.

Khan’s true legacy is his memory, a part of the collective conscious of many who remember him as the ‘Frontier Gandhi’, the apostle of non-violence who wanted both Hindus and Muslims to live in harmony under a United India—a dream that remains unfulfilled.

Courtesy: The Better India, dt. April 2, 2019.

|