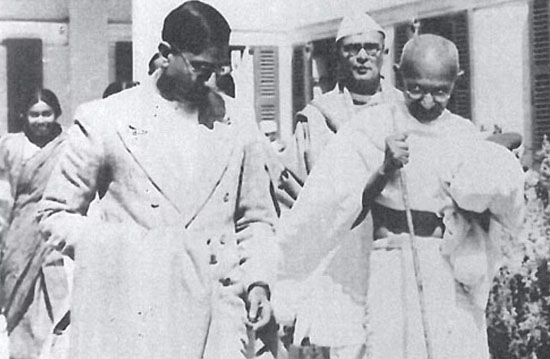

GD Birla: The ‘Nationalist Businessman’ Who Helped Fund The Freedom StruggleGhanshyam Das (GD) Birla, the architect behind the Indian business conglomerate, the Birla Group, had a very important role in the freedom struggle. Here’s his life story.- Rinchen Norbu Wangchuk GD Birla and MK Gandhi (Courtesy: Aditya Birla Group) A close associate of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi and friend to many leaders of the freedom struggle, GD Birla not only gave money for the cause but also built his own business empire despite the initial roadblocks set by the colonial administration, British and Scottish business interests and their Indian cronies. Leading the charge for Indian businesses, he played a pivotal role in the formation of the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI). Post-Independence, he founded the esteemed Birla Institute of Technology and Sciences (BITS) in his hometown of Pilani, Rajasthan. For his many contributions to the country, he was awarded the Padma Vibhushan by the Government of India in 1957. Early racism & the business giantBorn on 10 April 1894 in Pilani, Rajasthan, GD Birla underwent formal education only until the age of 11, after which he followed in his father Baldeodas’s footsteps into the family’s trading business in Mumbai and then Kolkata. As he once wrote, “In our village no one bothered with newspapers; not even half a dozen people would have read them. And where were the newspapers in those days? No one in the village could read and write English. Nor was there a school. A few people could read and write simple Hindi or Urdu, but perhaps only one in a hundred. At the age of four, I was put under a tutor who claimed to know more about arithmetic than reading and writing. And so my education began with futures – addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, etc. At the age of nine, I learnt a little reading and writing and got a smattering of English. My school education, however, ended with the ‘First Book Reading’ by Pyaricharan Sarkar, when I was only 11.” At age 16, he started his ‘independent business’ as a jute broker, and this is where he first encountered the racist practices of the English who were his patrons and clients. “During my association with them, I began to see their superiority in business methods, their organising capacity and their many other virtues. But their racial arrogance could not be concealed. I was not allowed to use the lift to go up to their offices, not their benches while waiting to see them. I smarted under these insults, and this created within me a political interest which, from 1912 until today, I have fully maintained,” he wrote. Desperate to transition from a trader to an industrialist, he made his foray into industrial manufacturing by setting up his first jute mill, Birla Jute Manufacturing Co Ltd, in Kolkata. He started this venture despite tremendous odds. British and Scottish merchants attempted to shut down his business by unethical and monopolistic methods like influencing the decision of certain banks to not give him a loan, besides the sudden change in currency exchange rates during World War I which made importing machinery from Britain a costly affair. He nonetheless soldiered on. From jute, he proceeded to get into the cotton textile industry. In the 1930s, he established sugar and paper mills, and by the 1940s, made his way into the automobile industry with the establishment of Hindustan Motors. As the Birla archives note, however, the real boom for the Birla empire “came after Independence when Birla invested in European tea, textiles and other industries”. Suffice to say, his business went on to reach incredible heights. The ‘nationalist businessman’Known as a ‘nationalist businessman’, GD Birla put his money where it counted by supporting the freedom struggle monetarily unlike some of his more conservative and establishment-oriented rivals who wanted nothing to do with the Indian National Congress. In the early 1920s, he created the Indian Chamber of Commerce, which emerged from his support of domestic enterprise, distaste for foreign goods and exit from the Marwari Association, a major trade organisation at the time, following a myriad of disagreements. The objective of this body was “to speak for Indian business and political interest”. Representing Indian businesses in Kolkata, business historian Gita Piramal notes that this body was in direct conflict with both the Bengal Chamber of Commerce, “a stronghold of British business in India”. Aside from getting elected to the Central Legislative Assembly in 1926, he set up FICCI alongside Puroshotamdas Thakurdas, Lala Harkishen Lal, BF Madon, DP Khaitan, AC Banerjee and Dinshaw Petit. As Piramal wrote, “In record time, Birla and Thakurdas managed to endow FICCI with an all-India character.” Unlike other Indian business associations at the time, FICCI and the Indian Chamber of Commerce expressed their support for the freedom struggle. As Piramal noted, “Under GD’s leadership the chamber enthusiastically participated in the All-Parties Conference of 1928 which produced the Nehru report asking for full dominion status.” Following the end of the civil disobedience movement in January 1932, the chamber “firmly condemned Gandhi’s arrest and the repression unleashed by the British”. Also, during the Quit India Movement of 1942, Birla came up with the idea of creating a commercial bank backed by Indian capital and management. This gave birth to the United Commercial Bank Limited, which is today known as UCO Bank, in 1943 in Kolkata. A public sector bank today, it remains one of the oldest major commercial banks in India. He was also part of a group of industrialists and technocrats alongside the likes of JRD Tata, Purushottamdas Thakurdas and John Mathai, who formulated the famous ‘Bombay Plan’, a 15-year economic plan for India, in 1944. A Quartz article notes the purpose behind the effort was the following: “The government (they meant the future government of free India) might take populist economic measures in a hurry after the war. Such measures were all the more likely if the government faced organised political demands for redistribution of income and wealth. These measures would harm the prospects of India’s economic development in the long run. However, this possibility could be avoided by proceeding in an orderly and more caring path of development before such a contingency arose.” Of course, this plan spoke for the protection of business interests, but alas Prime Minister Nehru went in another direction with his policies. Relationship with GandhiIn a column for The Wire, Venu Madhav Govindu, a professor at the Indian Institute of Science with in-depth scholarship on MK Gandhi’s economic policies, wrote, “In a broader sense, Indian capitalists were averse to the mass mobilisation orchestrated by the Congress under Gandhi’s leadership as they saw it as a threat to their economic interests. At the same time, these businessmen smarted against the constraints imposed on them by a colonial regime.” He added, “By the late 1920s, unable to ignore the growth of nationalism, India’s capitalists began to build an uneasy and cautious alliance with the Congress. GD played a special role in this entente and walked the tightrope of maintaining equations with both the Raj and the Congress. But his equation with Gandhi was also deeply personal. Indeed, as their extensive correspondence shows, the two men disagreed on many counts, but Birla continued to support many of Gandhi’s ashram activities as well as a range of constructive programmes.” Birla met Gandhi for the first time in 1916. In a 1979 interview with India Today, Birla said, “Of course, my ambition was to meet all the big people struggling for India’s Independence. Gandhiji came into my life because I went to him. I wanted to know him, and I must say that I was greatly benefited by that great soul.” In a four-volume collection of letters published by GD Birla called ‘Bapu: A Unique Association’, he states how they had little in common. However, Gandhi would end up becoming the “dominant influence” in his life. “Gandhiji’s influence on me was more through his religious character–his sincerity and search for truth–than his power as a political leader.” Considering himself as an unofficial emissary between Gandhi and the British business class, he wrote, “While at times I feel disappointed, I also feel that I am amply compensated in having to defend Englishmen before Bapu, and Bapu before Englishmen.” And what’s more, Birla supported Gandhi’s political activities monetarily with some reports citing that he even donated Rs 300 for his monthly living expenses. As Birla said, “Whatever sum Gandhiji asked from me, he knew that he would get it because there was nothing I could refuse him.” This doesn’t mean Gandhi did Birla’s bidding. According to academic Shraddha Jha’s 1991 paper, “[Gandhi] took his own decisions on critical issues such as the launching of the non-cooperation, civil disobedience, in 1930, the signing of the Gandhi-Irwin pact in 1931 and the withdrawal of the civil disobedience in 1933. If he had any effective influence on Gandhi, Birla would have prevented him from launching such non-violent movements.” In fact, there is a letter that Birla wrote to Mahadev Desai, Gandhi’s secretary, on 8 March 1940, which states, “You know I hate the civil disobedience Movement. In the name of non-violence, it has encouraged violence. In the name of construction, it has destroyed many things…The truth is that none believe in non-violence. Everybody in political circles wants upheavals…I can say for myself that I have no living faith in it.” Nonetheless, as Jha added, “…Birla came close to Gandhi and tried his best to keep him informed about the intentions of the British government.” This became apparent as he took part in the first and second Round Table Conferences in London along with Gandhi. And they had their differences too. While Gandhi was determined to seek unity between Hindus and Muslims, Birla saw nothing wrong in the forcible conversion of Muslims to Hinduism. “I have gathered from old writings that many Hindus were converted to Islam forcibly…I do not see the harm if the Arya Samajists do a bit of proselytising by resorting to force, and thereby add to the number of Hindus,” he wrote in a letter to Gandhi. Despite all this, GD Birla worked extensively in Gandhi’s programmes. As president of the Harijan Sevak Sangh, a non-profit founded by Gandhi in 1932, to eradicate untouchability in India, he set up hostels and schools for the Dalit community. Birla said, “Needless to say, my own experience as an out-caste from my own community greatly increased by sympathies with the depressed classes and made me further Bapu’s campaign for the Harijans.” Gandhi would go on to spend the last four months of his life at Birla House, a 12-bedroom house built by GD Birla in 1928, which also hosted many leaders of the Congress. It was there that Gandhi was assassinated by the terrorist Nathuram Godse on 30 January 1948. Devastated by the incident, he would later go on to say, “The last I saw of Gandhiji was his dead body. No friends could protect him. I myself used to attend the prayers with a pistol concealed in my belt and used to watch every soul who moved towards him. But this was all vanity.” Following Gandhi’s passing, Birla continued his work as a philanthropist and institution-builder helping set up schools, colleges, temples, hospitals and even planetariums across India. Aside from establishing BITS Pilani, which has produced generations of world-class scientists and engineers, he also supported educational institutions like the Aligarh Muslim University and Banaras Hindu University. Till his eventual demise on 11 June 1983, he remained true to expanding his business to new heights, while not losing sight of the spirit of philanthropy. Courtesy: The Better India, dt. 08.06.2022 |