Some men changed their times...

One man changed the World for all times!

Comprehensive Website on the life and works of

Mahatma Gandhi

+91-23872061

+91-9022483828

info@mkgandhi.org

+91-23872061

+91-9022483828

info@mkgandhi.org

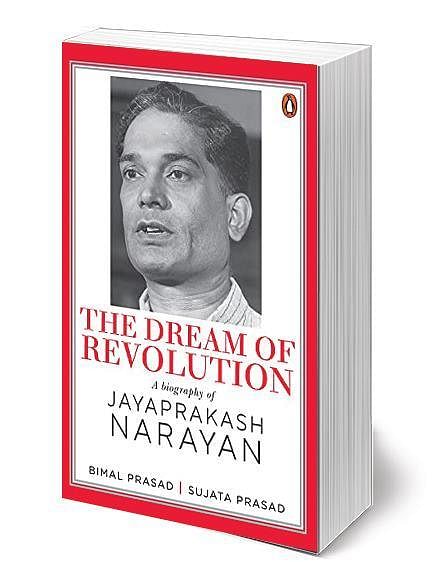

Jayaprakash Narayan, the Gandhi of the emergency eraThe journey of this extraordinary man has been brought to life in a biography of JP titled 'The Dream of Revolution' by Bimal Prasad, a noted scholar and close associate of JP, and Sujata Prasad. |

- A Surya Prakash  For those of us who have lived through and survived the tumultuous 1970s, including the harsh realities of the Emergency imposed by Indira Gandhi, the name of Jayaprakash Narayan or JP evokes reverence, not just for his singular contribution to the restoration of democracy, but for reinforcing the idea that one needs moral force to stand up to tyranny. JP was the Gandhi that India needed in the second half of the 20th century, when the youth felt disenchanted with poor governance, corruption and the lethargic pace of development. He virtually stepped into the Mahatma’s shoes when everything seemed to be falling apart in the 1970s because of the growing unrest among students. And when he took the lead, calling for a “total revolution”, Indira Gandhi hit back by throttling democracy and jailing her opponents. Despite his deteriorating health, JP made great sacrifices to fight the Emergency regime, stitch up a rag-tag coalition of disparate political entities, ensure the defeat of Indira Gandhi and the restoration of democracy. This was certainly the most challenging assignment that JP gave unto himself. But this was not the only one. The journey of this extraordinary man has been brought to life in a biography of JP titled The Dream of Revolution by Bimal Prasad, a noted scholar and close associate of JP, and Sujata Prasad. This is an exceptional book for several reasons. It is based on JP’s papers, diligently put together by Bimal Prasad in 10 volumes, and provides invaluable insights into JP’s association with Gandhi, Nehru, Patel and the communists. The authors must be complimented for the detachment with which they have dealt with the subject despite their proximity to the man. The authors say that as one of the founders of the Congress Socialist Party (CSP), JP outlined his ideological position in Why Socialism published in 1936. It was radical enough to attract the attention of the likes of EMS Namboodiripad. For JP, every ideology seemed to be like the curate’s egg—good in parts. As a result, JP’s dalliance with every ‘ism’ appears to be subject to what one may call “JP’s Lakshman Rekha”. Take the case of Gandhi, under whose influence he came after his return from the US. Some years hence, he debunked Gandhism as a “dangerous doctrine” and “a compound of timid economic analysis, good intentions and ineffective moralising...”. As regards Marx, Minoo Masani recalls that while he (Masani) was a staunch democrat of the British Labour Party, “JP was a staunch believer in the dictatorship of the proletariat...”. But, JP had later argued that “it is a common mistake to think that there must be dictatorship of the proletariat in a Socialist state”. Then came his initiative in January 1936 to induct members of the Communist Party of India (CPI) into the CSP only to lament four years later that the communists were trying to “crush” the CSP. He also accused them of being “Russia’s fifth columnist”. Then, there was JP, the man of contradictions. While he was a strong advocate of non-violence, he publicly declared his support to Naxalites in June 1969. Another important strand that runs through this book is the blow hot, blow cold relationship between JP and Indira Gandhi. The authors note that the disagreements between the two were without rancour until about 1970. Thereafter, the relationship deteriorated. “He was lionised for a brand of politics that was free of compromises,” say the authors. How true. JP appeared to be eternally chasing his dream of an ideal world. Alas, that was not to be. He felt terribly betrayed by the crass politics of the Janata Parivar, which destroyed his dream of a total revolution. But that is not to say that JP’s journey was futile. He has left behind a great legacy and many provisions in the Indian Constitution, specially Articles 38, 39, 41, 42 and 43, show how much the idealism of JP and his fellow-travellers influenced the constitution-makers. Idealists may find themselves lost in the rough and tumble of politics, but nations and societies in pursuit of the larger good can never ignore them, because they are the eternal conscience-keepers. Courtesy: The New Indian Express, dt. 28.12.2021 Click here to buy the book |